ALSO BY STEFANO MANCUSO

The Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and Behavior

Brilliant Green: The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence

Originally published in Italian as Lincredibile viaggio delle piante in 2018 by Editori Laterza, Rome.

Copyright 2018 Gius. Laterza & Figli

English translation copyright 2020 Gregory Conti

Production editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas

Text designer: Jennifer Daddio / Bookmark Design & Media Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

For information write to Other Press LLC, 267 Fifth Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Mancuso, Stefano, author. | Conti, Gregory, 1952- translator.

Title: The incredible journey of plants / Stefano Mancuso; watercolors by Grisha Fischer; translated from the Italian by Gregory Conti.

Description: New York : Other Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019027763 (print) | LCCN 2019027764 (ebook) | ISBN 9781635429916 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781635429923 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: PlantsMigration.

Classification: LCC QK101 (print) | LCC QK101 (ebook) | DDC 581.3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019027763

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019027764

Ebook ISBN9781635429923

v5.4

a

TO ROSARIA AND FRANCO

my parents

PREFACE

Do you remember the Frank Capra masterpiece Its a Wonderful Life, with James Stewart as the unforgettable George Bailey? I really hope you all know it. The plot of the film is very simple: its centered around the sacrifices of dreams and aspirations that the hero, George Bailey, makes his whole life long just for the sake of helping others.

Do you remember the Frank Capra masterpiece Its a Wonderful Life, with James Stewart as the unforgettable George Bailey? I really hope you all know it. The plot of the film is very simple: its centered around the sacrifices of dreams and aspirations that the hero, George Bailey, makes his whole life long just for the sake of helping others.

As a child, George saves his brother, Harry, from drowning in a frozen pond, becoming deaf in one ear in the process. As an adult, he gives up his own dreams in order to manage the small building and loan founded by his father. George gives his college tuition money to brother Harry so that Harry can go to college. When George gets married, in 1929, the year of the Wall Street crash, he uses the money he had saved for his honeymoon to keep the building and loan solvent and avoid bankruptcy. Sacrifice after sacrifice, Georges life goes by unobserved until, owing to a series of events I wont go into, our hero decides to kill himself. He is about to throw himself into the river when Clarence (Angel Second Class) saves him, transports him into a parallel world, and shows George what the real world would have been like had he never been born.

I know: when its recounted like this its tough to keep a straight face, but Capra is able to take an edifying Christmas story and turn it into one of the milestones of cinema history. Actually, now that Ive talked to you about it, I cant wait for Christmas so I can have the chance to see it again.

Well, plants are the George Baileys of this planet. Nobody pays them respect; they are studied much less than animals; we have no more than a vague idea of how many of them there are, how they work, what their characteristics are. Yet, without them, the life of each of us animals would not be possible. It would be instructive if a master of cinema of the caliber of Frank Capra could show us one day what our world would be like if plants had never been born.

We know very little about plants, and, quite often, the little we think we know is wrong. We are convinced that plants are not able to perceive the environment around them, while in reality, quite to the contrary, they are more sensitive than animals. We are sure that plants belong to a silent world, deprived of the ability to communicate, but, instead, plants are great communicators. We are convinced that they dont carry on any kind of social relationship, but, quite the opposite, they are exquisitely social organisms. We are, above all, absolutely certain that plants are immobile. On this point, we are immovable. Plants do not move; after all, just look at them. Isnt the big difference between animal (that is, animated, endowed with movement) and vegetable organisms exactly that?

Actually, were wrong about this one, too. Plants are not immobile at all. They move a lot, only at a slower pace. Plants are not unable to move. What plants are unable to do is locomote, or move from place to place, at least not in the course of their lifetimes. The adjective that defines them, in fact, should not be immobile but sessile, or, if you prefer, rooted. A sessile organism cannot move from the place where it was born, but it can move, how and as much as it likes. Thats what plants do, and each of us can understand that just by taking a look at one of the thousands of time-lapse videos that can be found all over the internet.

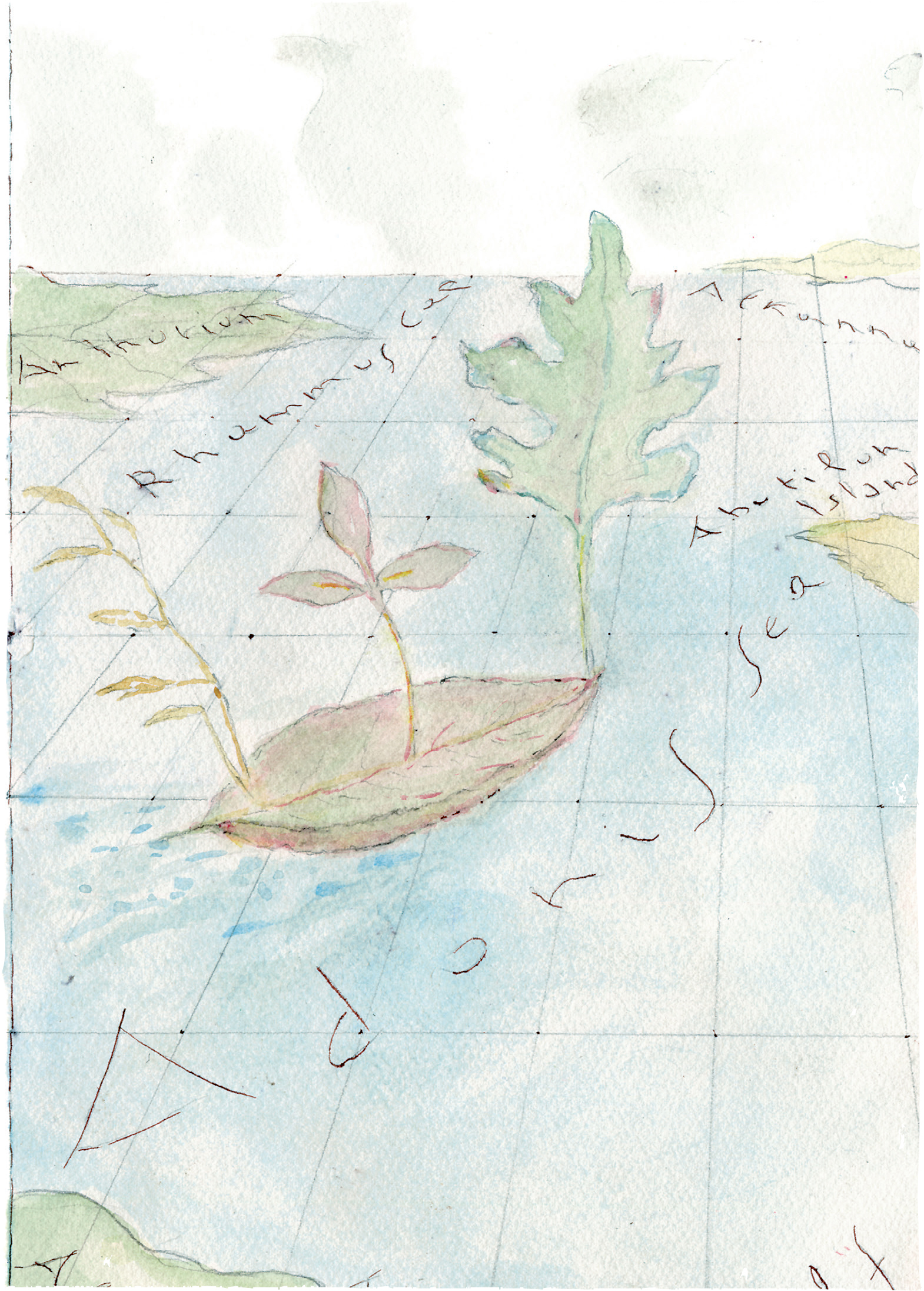

Although plants are not able to change places over the course of their individual lives, they are able, from generation to generation, to conquer the most distant lands, the most impervious areas, and the regions least hospitable to life, with a tenacity and capacity for adaptation that have often left me envious.

As I have written elsewhere, plants are incredibly different from animals. Their bodies, their architecture, their strategies are often diametrically opposed to those of animals. Animals have one command center; plants are multicentric. Animals have single or double organs; plants have diffuse organs. Animals are individuals (in the sense of being indivisible); plants are not individuals at all, being more like colonies. In a word, it would seem that the emphasis in animals is more on the singular, while in plants its more on the plural. In animals, the individual counts more; in plants, the group. Organisms so different from us must be observed through the lens of comprehension or inclusion, not through the lens of similitude. We will never be able to understand plants if we look at them as if they were impaired animals. They are a form of life that is different, neither simpler nor less developed, than the animal form of life.

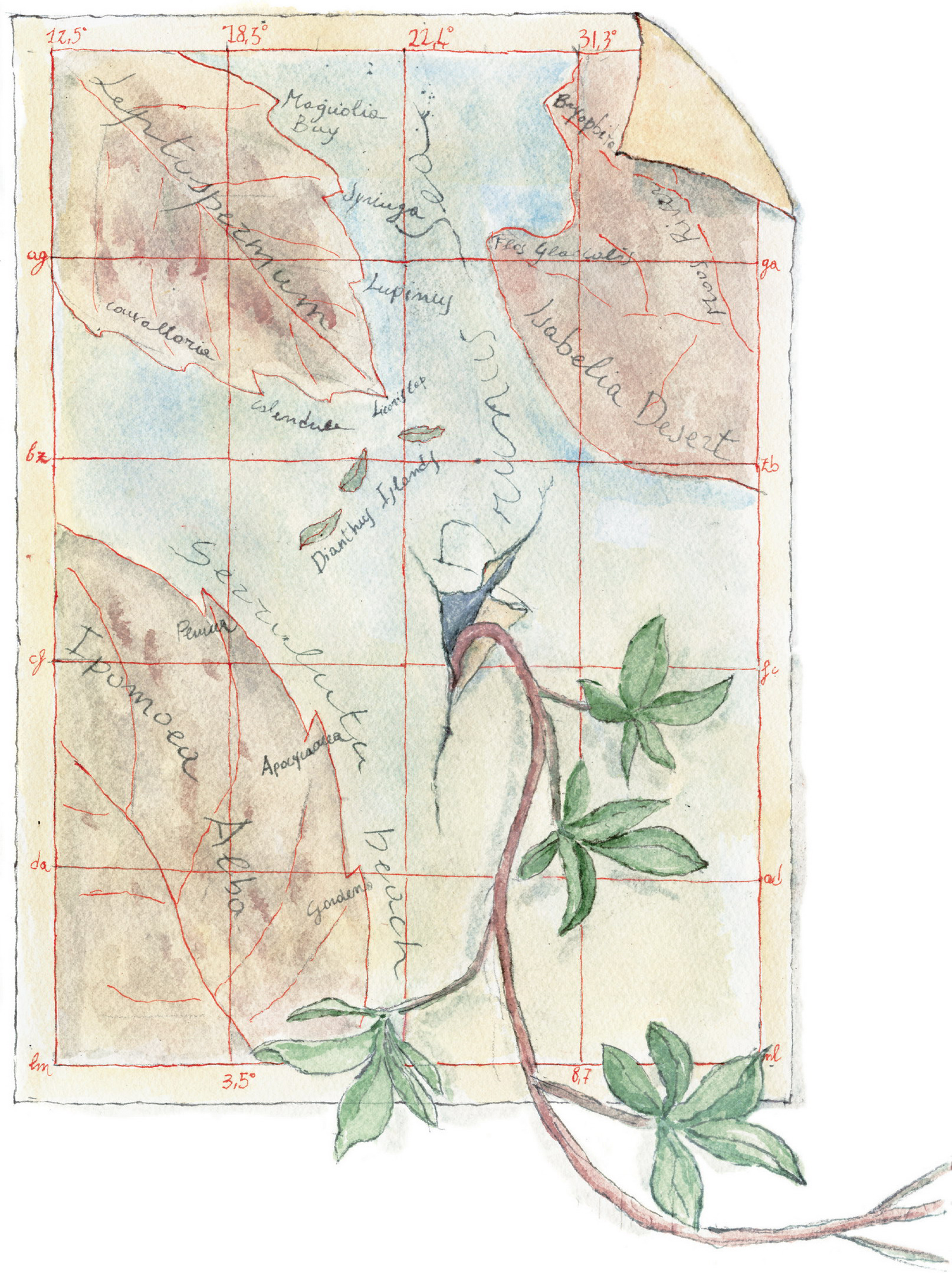

If they are looked at through eyes without an animal filter, their extraordinary characteristics emerge clearly and indubitably, everywhere, even in areas where it would seem unlikely, as in their ability to move. When it comes to migrants and migration, it is helpful to study plants in order to understand that we are talking about an unstoppable phenomenon. Generation after generation, using spores, seeds, or any other means, vegetables move about and advance through the world, conquering new spaces. Ferns release astronomical quantities of spores that can be transported by the wind for thousands of miles, for years and years. The number and variety of instruments by way of which seeds are dispersed in the environment are astounding. It is as if, over the course of evolution, every single possibility has been taken into consideration and, at one time or another, each of the tested solutions has found some species ready to try it.

Do you remember the Frank Capra masterpiece Its a Wonderful Life, with James Stewart as the unforgettable George Bailey? I really hope you all know it. The plot of the film is very simple: its centered around the sacrifices of dreams and aspirations that the hero, George Bailey, makes his whole life long just for the sake of helping others.

Do you remember the Frank Capra masterpiece Its a Wonderful Life, with James Stewart as the unforgettable George Bailey? I really hope you all know it. The plot of the film is very simple: its centered around the sacrifices of dreams and aspirations that the hero, George Bailey, makes his whole life long just for the sake of helping others.