Contents

Guide

Copyright 2021 by Alex Harris

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

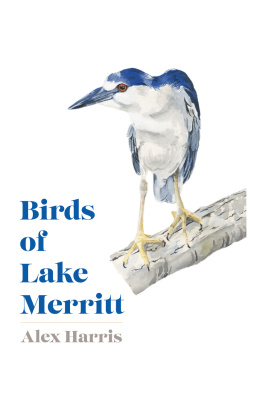

Names: Harris, Alex, 1983- author, illustrator.

Title: Birds of Lake Merritt / Alex Harris.

Description: Berkeley, California : Heyday, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021010506 (print) | LCCN 2021010507 (ebook) | ISBN 9781597145480 (board) | ISBN 9781597145619 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Water birds--California--Merritt, Lake--Identification. Classification: LCC QL678.5 .H37 2021 (print) | LCC QL678.5 (ebook) | DDC 598.17609794/66--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021010506

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021010507

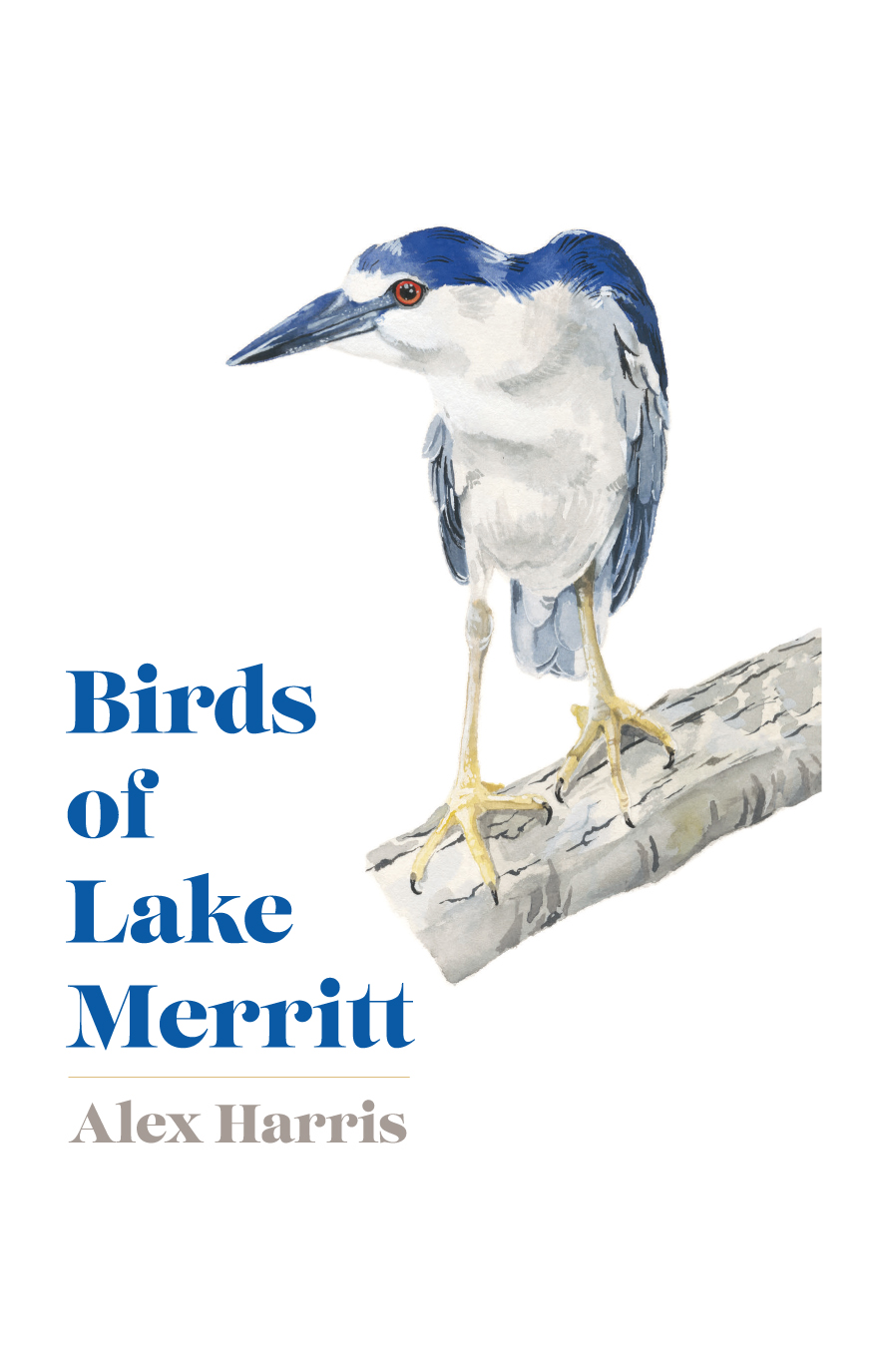

Cover Art: Alex Harris

Cover Design: Ashley Ingram

Interior Design/Typesetting: Ashley Ingram

Published by Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, California 94709

(510) 549-3564

heydaybooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Dedicated to my familythanks for everything

Contents

Acknowledgments

Thanks and appreciation to all who gave their time and attention to this book.

Allie for her endless support.

Natalie Jones, Nina Lewallen Hufford, L. John Harris, Alec Scott, Lynn Schofield, Michele D. Jones, and Marthine Satris for editing.

Ashley Ingram and Diane Lee for making everything look good.

Heyday, for having me.

Everyone who contributed their words or shared their experiences with me: Timbo, Jenny Odell, Rue Mapp, Cindy Margulis, Clayton Anderson. My dad for always encouraging my artistic endeavors. The Oakland Library, Walden Pond, and Spectator Books for books and source materials. Corrina and Deja Gould for fact checking and editing the Ohlone history. Julian Marszalek and Nina Mae Haggerty for general support and discussion. Sally for teaching me how to draw, Ajene for inspiration, and Maria Schoettler and Leah Tumerman for artistic encouragement. David Weidenfeld for his love of books. Those who did all the hard work of developing the historical, scientific, and cultural knowledge that this book drew upon.

Introduction

THE WILDLIFE REFUGE IN THE HEART OF OAKLAND

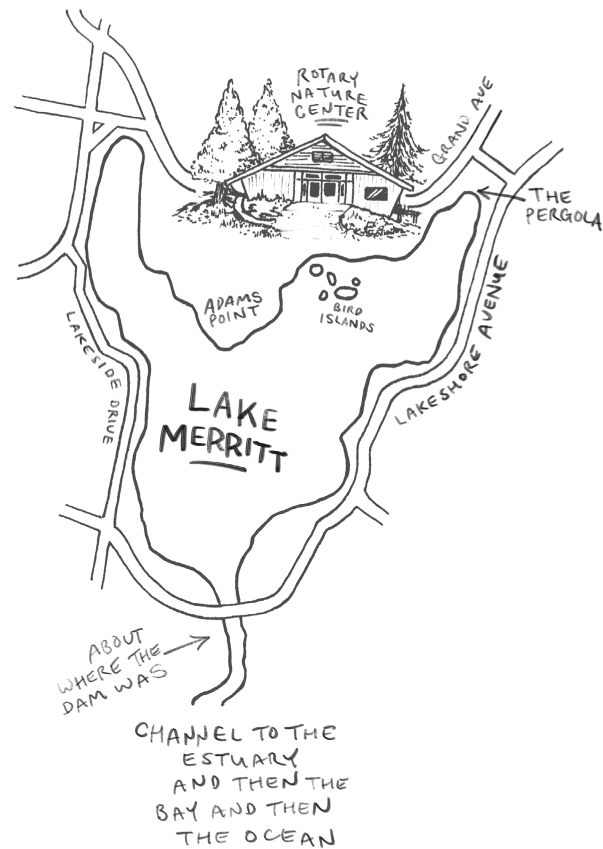

Lake Merritt has been called the heart of the city of Oakland, as well as its lungs. It is the crown jewel of Oakland, and said to be draped in a necklace of lights. Surrounded by parks and gardens, with the buildings of the city just beyond, the lake is at once at the center of the city and a welcome respite from it. People stroll along the scenic paved pathways, row across the glistening waters, and admire the city skyline while picnicking along the verdant ring of parkland surrounding it. Often, this grassy green oasis is dotted with goose poop. Along with the people, there are flocks of geese at the lake. They swim in the water, stand obstinately in the way of joggers, and nibble on the grass. There are many other birds who frequent the lake as well: ducks, herons, egrets, pelicans, grebes, cormorants, cootsand those are just the ones in the water; many other species live in the surrounding trees and gardens. But what are these birds doing in the middle of the city, and why do the residents of Oakland tolerate so much goose poop?

My interest in answering these questions began when I attempted to learn how to identify the various species of hawk that one might see in California by painting them, bird by bird, and at the same time get better at painting. Surely, spending ten hours painting a bird would help me to better understand gouache and watercolor, as well as enable me to differentiate between a Red-tailed and Coopers Hawk. Two birds with one stone. I found beautiful photographs of these birds and painted them as best I could. The paintings turned out fine, but what I failed to account for was that rarely, in day-today life, do you encounter hawks that are ten feet away, standing perfectly still on a fence post and staring straight at you, as many photographs of hawks would have you believe. It turns out that you mostly see hawks from beneath, hundreds of feet away, a blurred silhouette circling in the skies above. Painting from photographs had not prepared me for this. I decided that I should look a little closer to home, so I rode my bike over to the bird sanctuary at Lake Merritt.

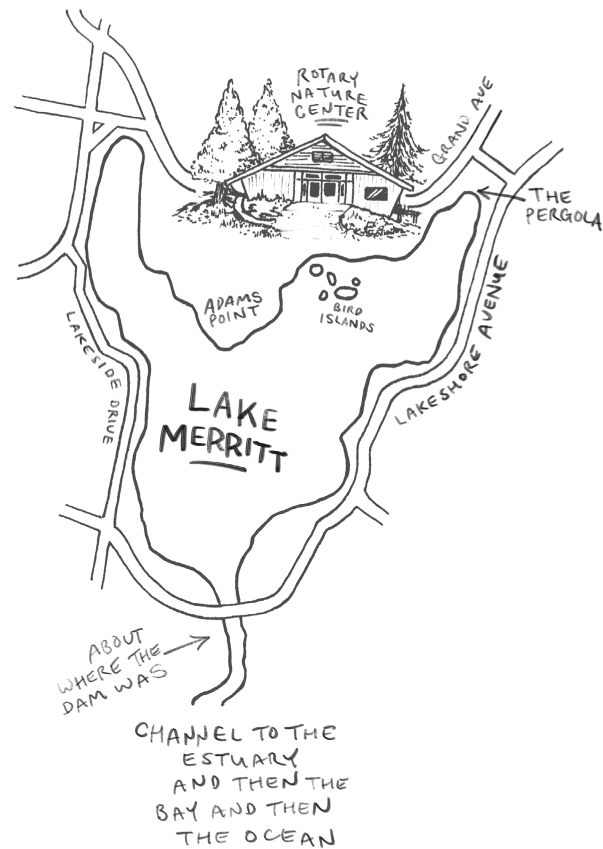

While I watched the ducks at the lake, I came across the then-shuttered Rotary Nature Center, which piqued my interest. I soon learned that Lake Merritt was the first wildlife refuge in the nation. Right here, in Oakland! I grew up in Berkeley, spent my teenage years exploring every nook and cranny of the East Bay (or so I thought), and even got a degree in environmental studies, but had no idea about this piece of important local environmental history. A trip to the Oakland History Room at the nearby library sent me on my way toward understanding the history of the wildlife refuge at Lake Merritt.

One hundred and fifty years ago, Samuel Merritt, a wealthy landowner and the mayor of Oakland, asked the State of California to ban bird hunting in the tidal estuary on the outskirts of the new city, and thus to create the first officially recognized wildlife refuge in the United States. The statute, passed on March 18, 1870, read: It shall be unlawful for any person to take, kill or destroy, in any manner whatever, any grouse, any species of wild duck, crane, heron, swan, pelican, snipe or any wild animal or game, of any kind or species whatever, upon, in or around Lake Merritt. And with that, the birds were now free to exist on the water and in the wetlands undisturbedto rest, hunt, raise families, and fertilize the lawns, and neighbors and visitors could observe them as they did.

But why look at birds? As an artist and nature-interested person, I think birds are cool to look at for their natural forms and traits: the alien technology of a coots foot, the cormorants dinosaur-like crooked neck, the complex colors of a duck. But birds also serve as a daily reminder that we humans are not the only ones here on this planet. As John Berger writes in the 1977 essay Why Look at Animals?: With their parallel lives, animals offer man a companionship which is different from any offered by human exchange. Different because it is a companionship offered to the loneliness of man as a species. Today, the wildlife refuge at Lake Merritt provides both the experience of marveling at the beauty of the birds variety of form and color and also a reminder that we are part of a large, complicated, beautiful world.