THE BOOK OF KELLS

Text compiled by Ben Mackworth-Praed

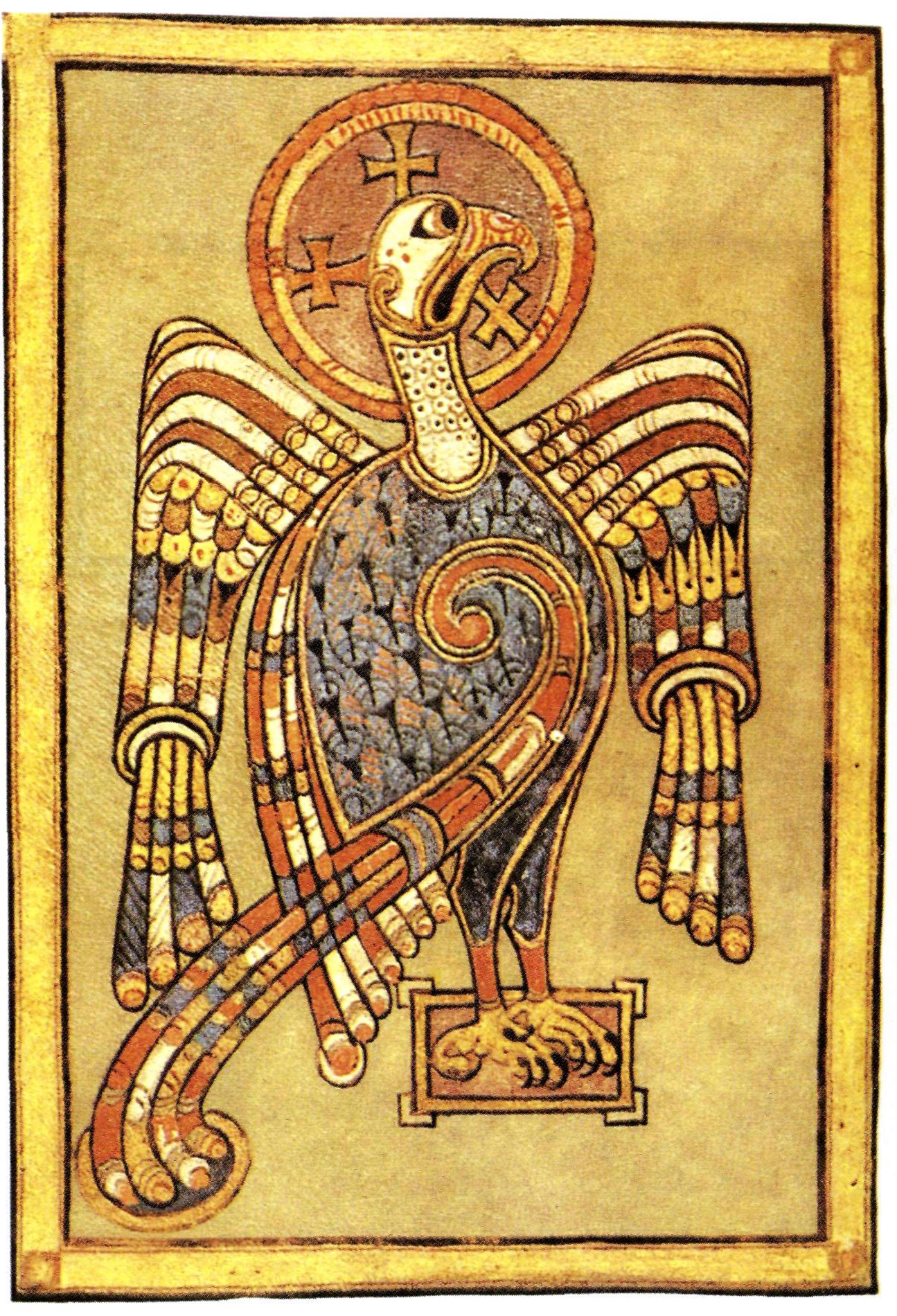

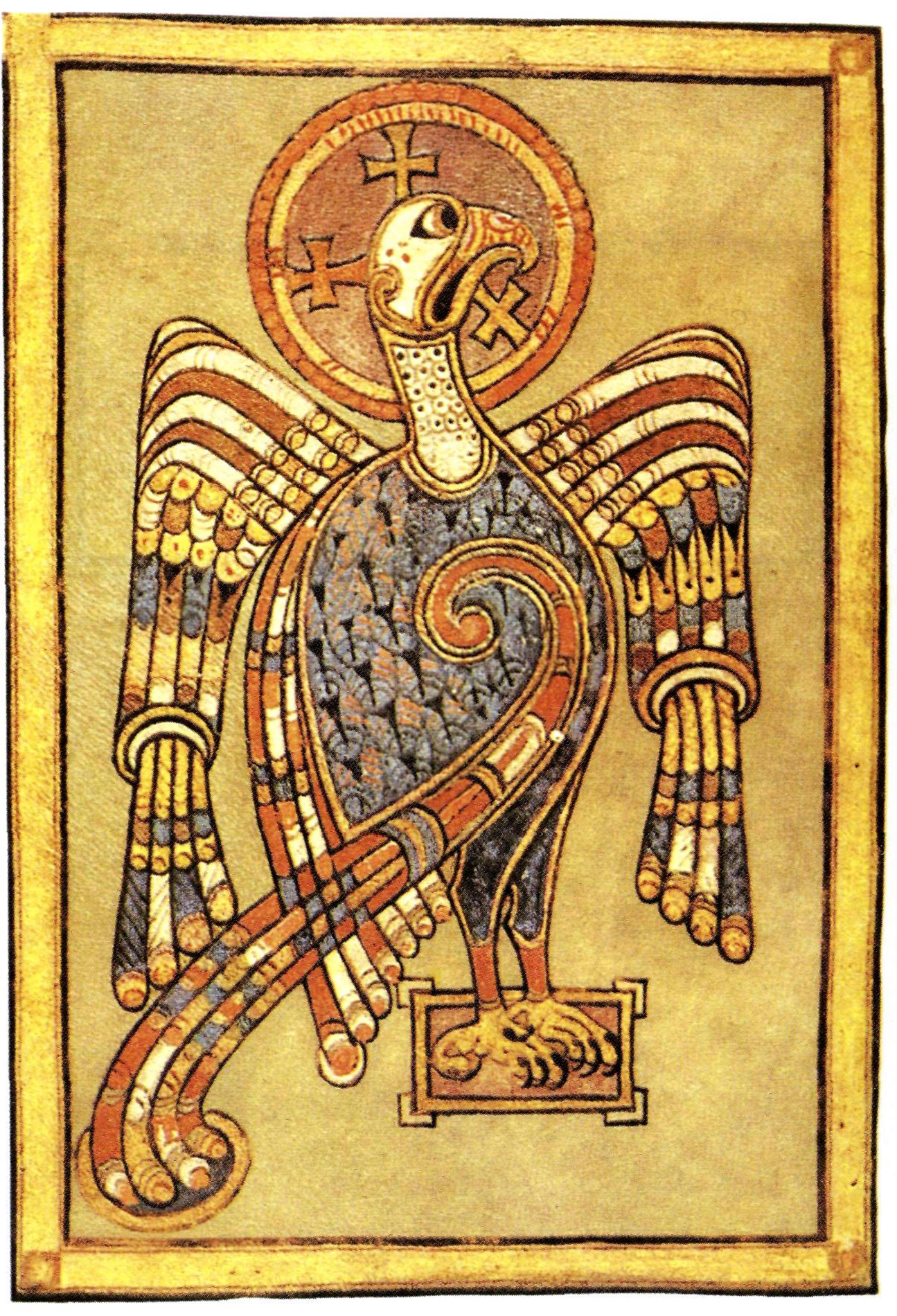

Frontispiece: The Eagle, symbol of St John, from the

Book of KeltsCONTENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

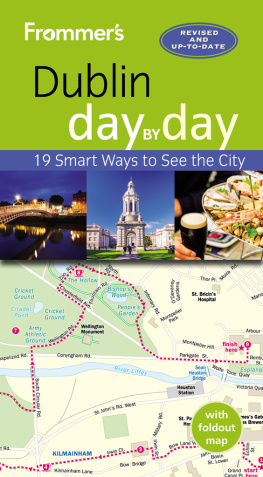

The Book of Kells, less widely known as the Book of Columba, is an ornately illustrated manuscript, produced by Celtic monks around AD 800 in the style known as Insular art. It is one of the more lavishly illuminated manuscripts to survive from the Middle Ages and has been described as one of the greatest examples of Western calligraphy and illumination. It contains the four gospels of the Bible in Latin, along with prefatory and explanatory matter decorated with numerous colourful illustrations and illuminations. Today it is on permanent display at the Trinity College Library in Dublin, Ireland where it attracts over 500,000 visitors per year.

INTRODUCTION

The Book of Kells is the richest, most copiously illuminated, manuscript version of the four Gospels in the Celto-Saxon style that still survives. But considering its fame, it is surprising that relatively little is known about it.

It consists of 339 vellum leaves, or folios, each one disastrously cropped by a nineteenth-century bookbinder, and covered with beautifully formed, black-ink script, the initial letters picked out in brightly coloured paints and ornamented with fantastic abstract animal and human forms.

We know that it once had more pages, for when Archbishop Ussher bought the book in 1621, he wrote in it that there were 344 folios. We think, judging by the parts missing from the Gospels of St Luke and St John that there may have been as many as 368 folios.

In fact it is surprising that so much of the book does survive! The Abbey of Kells, from where it is first known, was plundered at least seven times before 1006, when the book was stolen and buried for three months. When it was recovered its jewel-encrusted, golden cover had gone forever.

On the dissolution of the Abbey, the book probably passed to the family of the last abbot, and may have had several owners before being collected by Archbishop Ussher. When he died his daughter tried to sell it in Europe; Oliver Cromwell blocked this, and the book was sold to the army in Ireland instead. For five years it lay in an open room in Dublin Castle until 1661 when Charles II presented it to Usshers alma mater, Trinity College, Dublin where it remains.

That much we know. We do not know when or where the book was written or even who wrote it, although, according to legend, St Columba was the creator of this, perhaps the most beautiful of books.

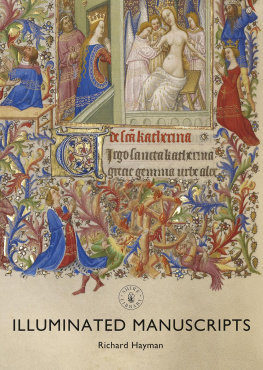

Before the invention of printing, the Gospels and other holy writings were copied out by hand. Conscious of the intrinsic value of a book as the sum of so many laborious hours, and the spiritual value of these works, the scribes took to ornamenting their manuscripts richly.

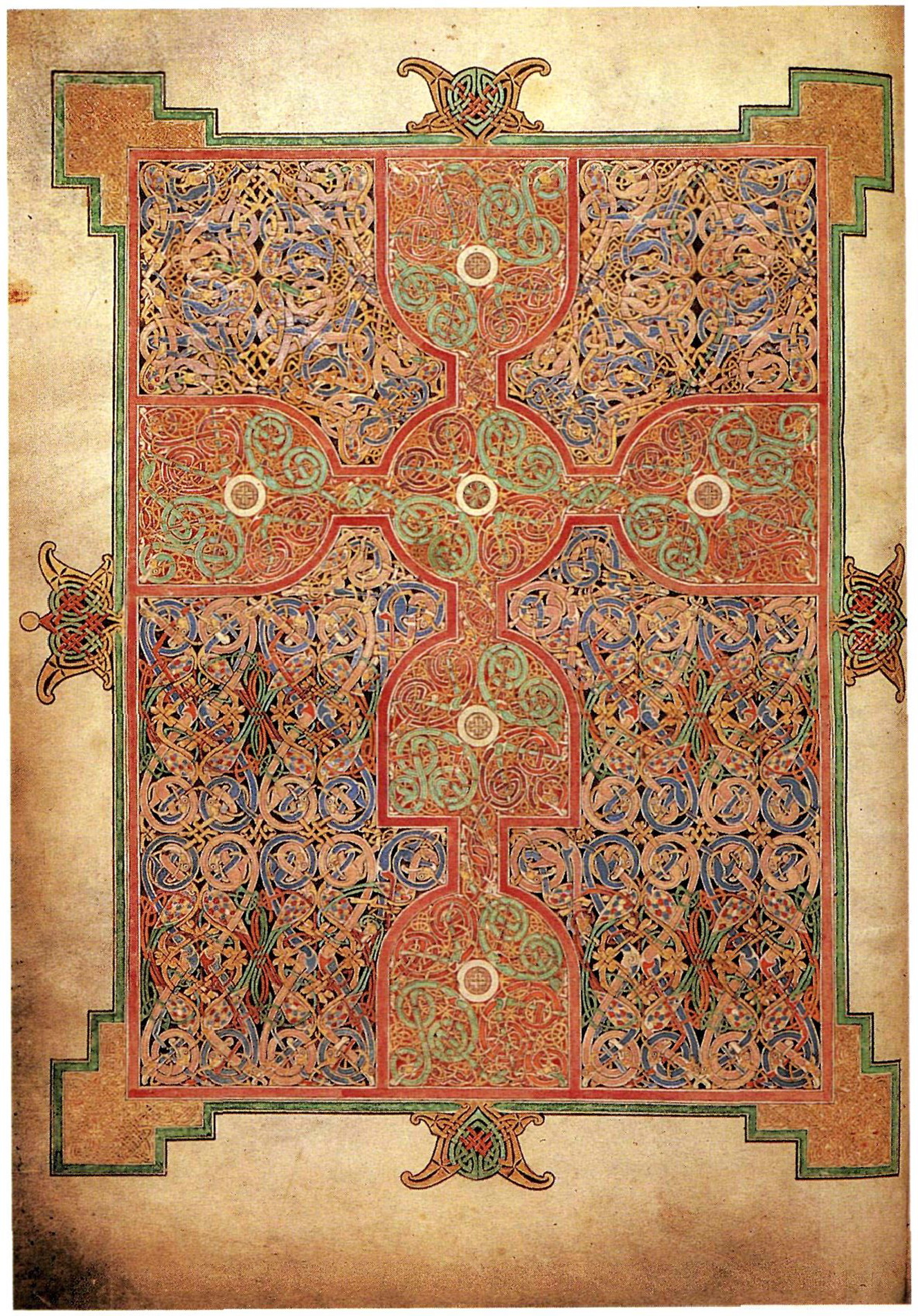

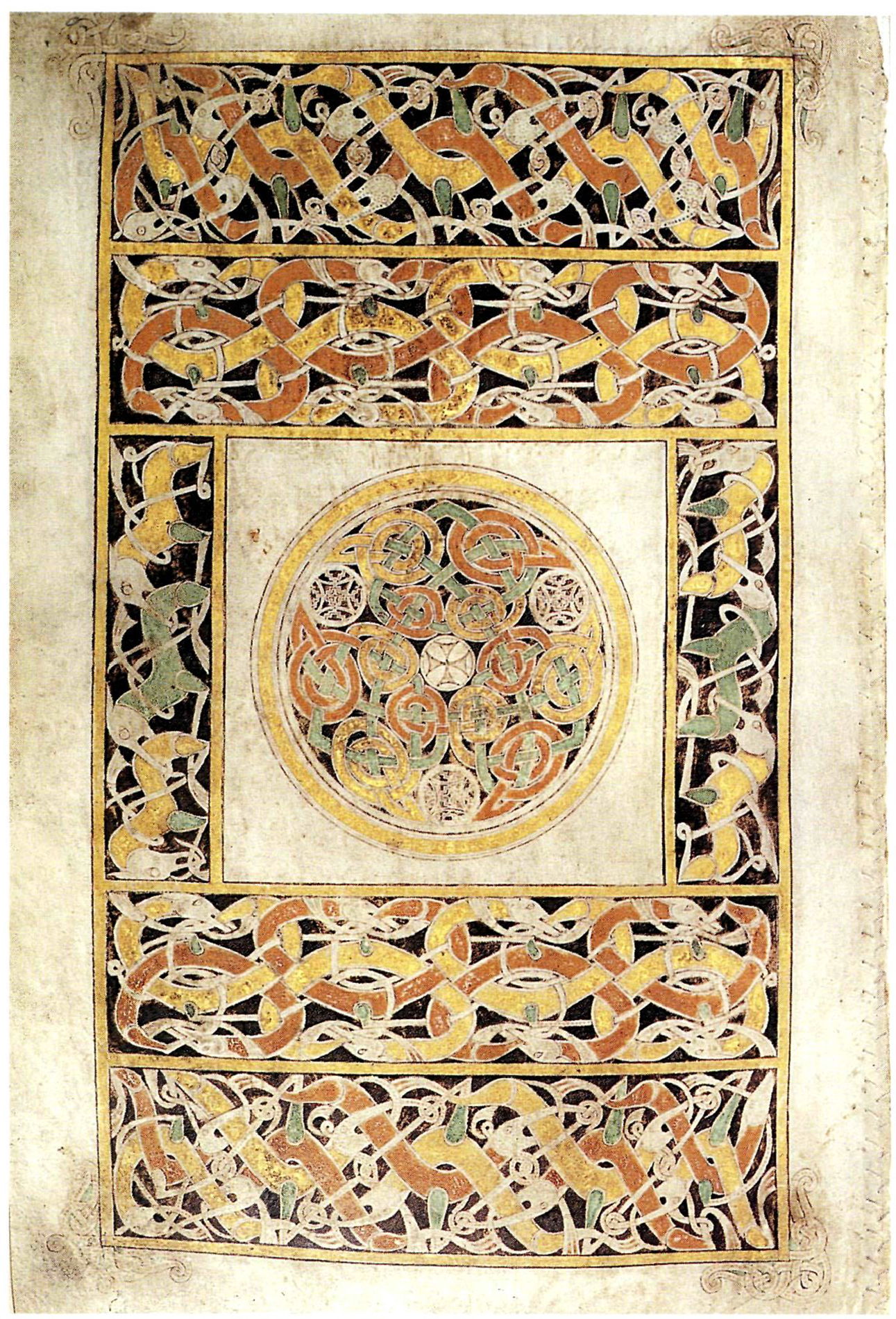

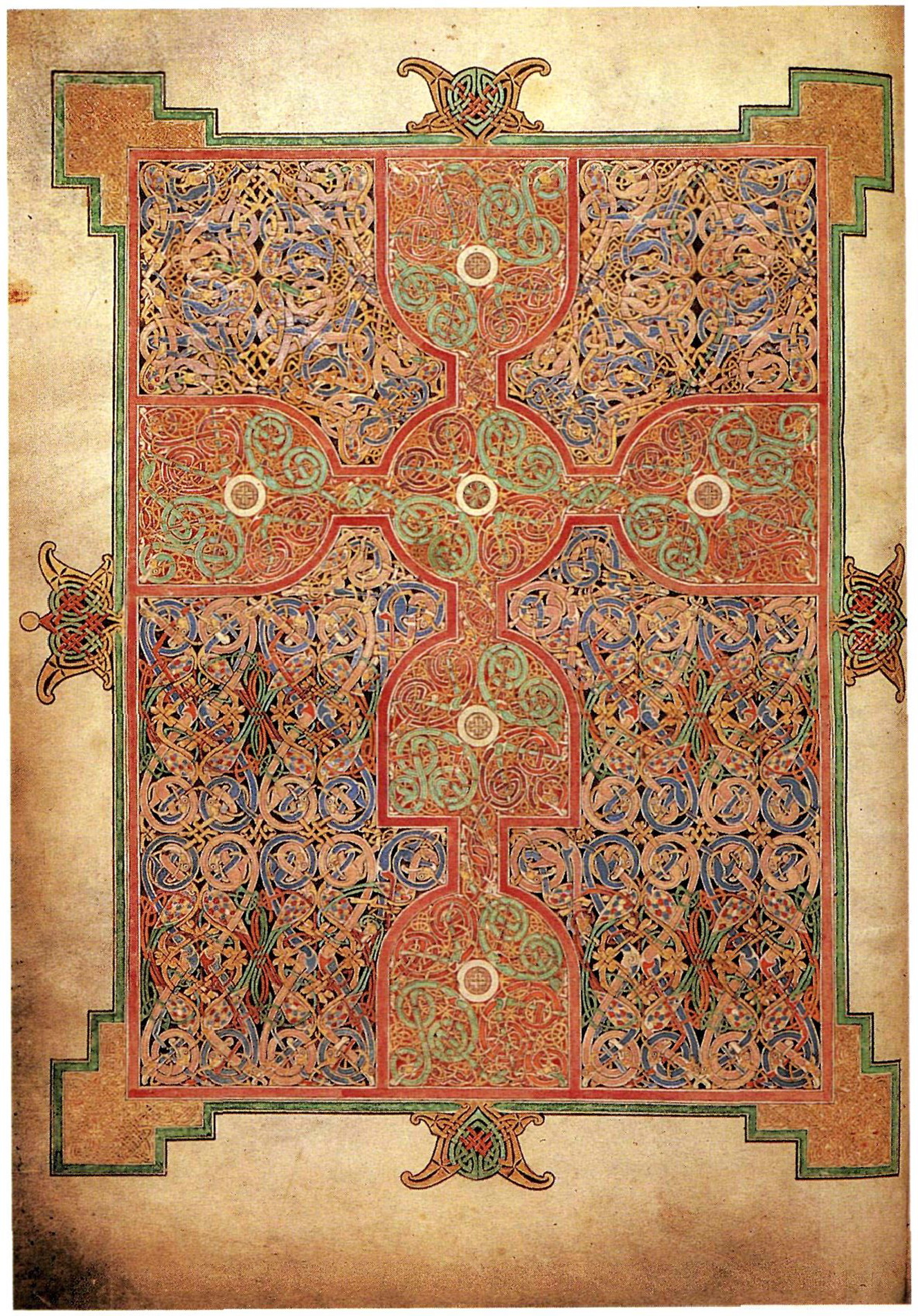

Carpet-cross from the

Book of Lindisfarne (c 695) decorated with interlace in the Celtic tradition.

Every region where Christianity flourished produced Gospels in its own particular style. But few decorated them with such magnificence as the monks of northern Britain and Ireland where the so-called Insular style evolved and flourished.

While Byzantine, Italian and Saxon art all influenced the Insular style, its mainspring was the skill in decorating metalwork and leather which the Celts brought with them when they arrived in Ireland from mainland Europe and Britain in pre-Christian times.

There were already isolated Christian communities in Ireland before St Patricks arrival there in 432. Pre-Christian culture that did not clash with Christianity was pressed into Christian service, and so the Celtic tradition of ornament was given a new outlet in the decoration of religious books that the new Church required.

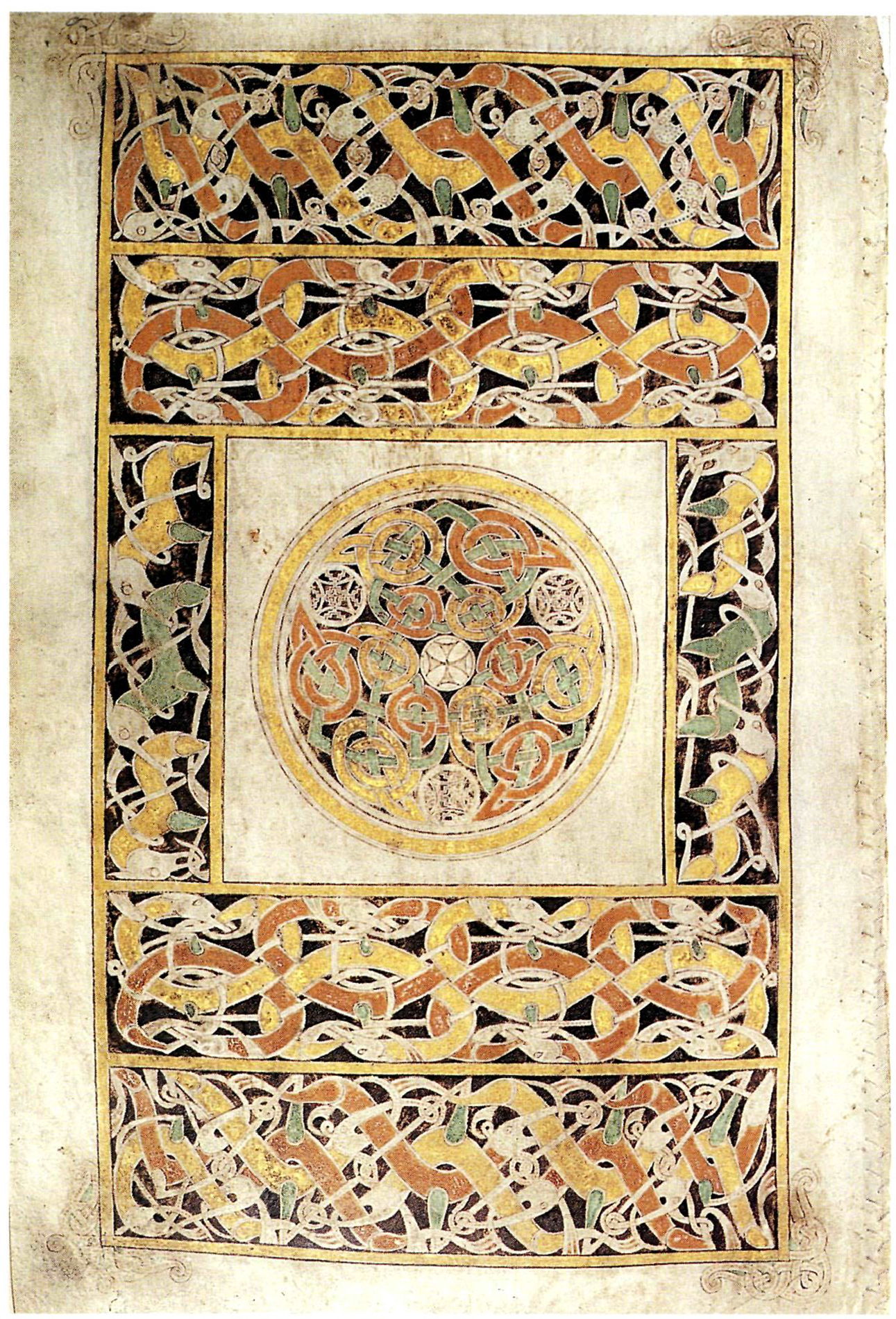

Carpet-page facing the beginning of the gospel of St John from the

Book of Durrow (c 680). Note the intricate animal and serpentine interlace. Carpet-pages are purely ornamental, often with reversible designs which can be viewed either way up.

In 563, St Columba, said to be the founder of the Abbey at Kells as well as the creator of its famous book, left Ireland for Iona in Scotland where he established a monastery that flourished for nearly 250 years.

By then in England, successive Saxon invasions had effectively wiped out Christianity, and it was not until 597, when St Augustine from Rome arrived in Kent that the religion was re-established in England.

Christianity was taken to northern England when a Christian, Kentish princess married Edwin of Northumbria. The couples heirs were sent to Iona to be educated and, later, invited St Aidan to come from there to found a monastery at Lindisfarne.

Aidan and his monks brought with them the Celtic traditions of illuminating manuscripts, examples of which can be seen in the Cathach of St Columba, the Codex Ussherianus Primus and the Book of Durrow. At Lindisfarne, mingling these Celtic traditions with native Saxon art and the influences of Rome and Byzantine, the monks created the marvellous Durham Gospels and Book of Lindisfarne.

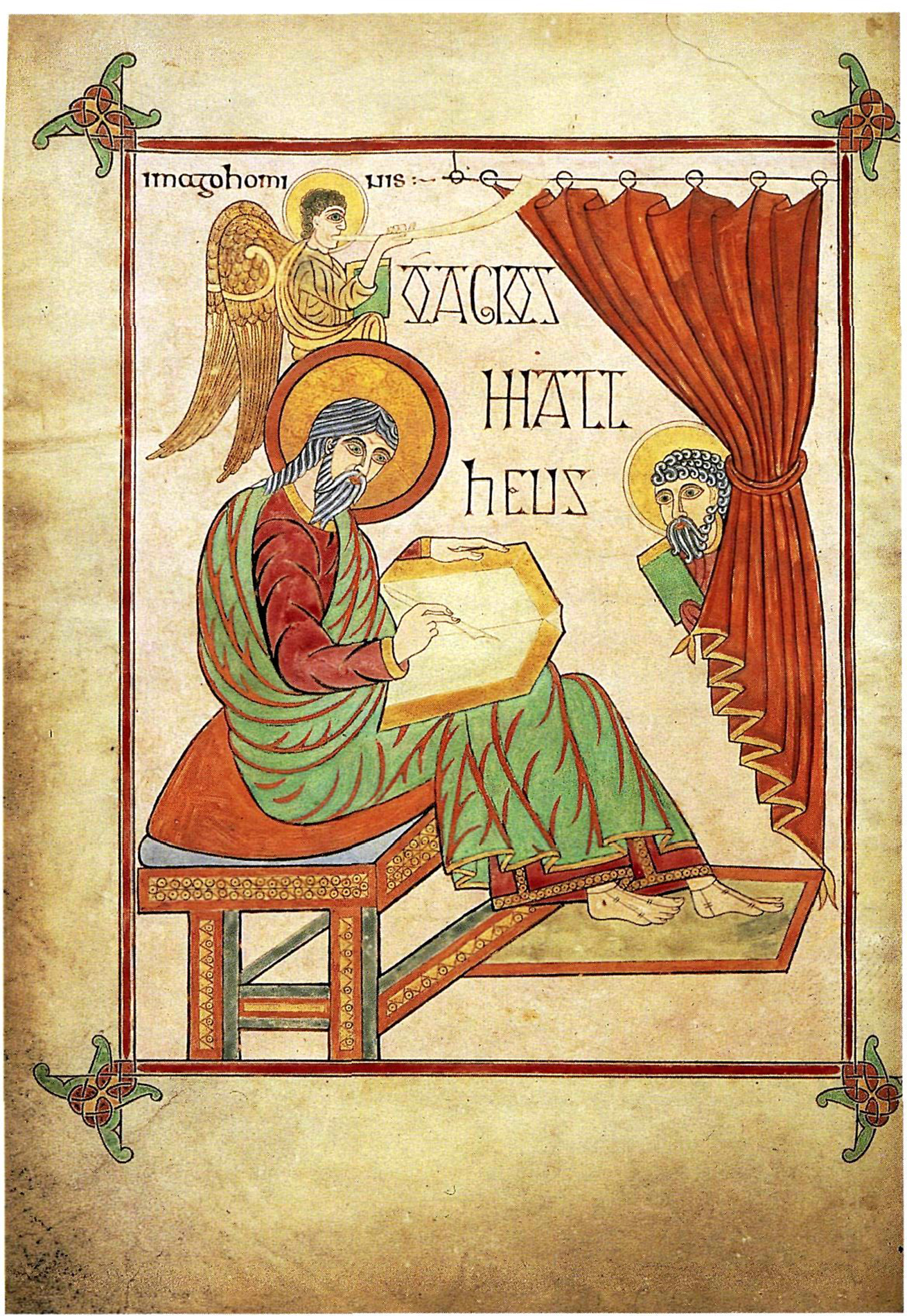

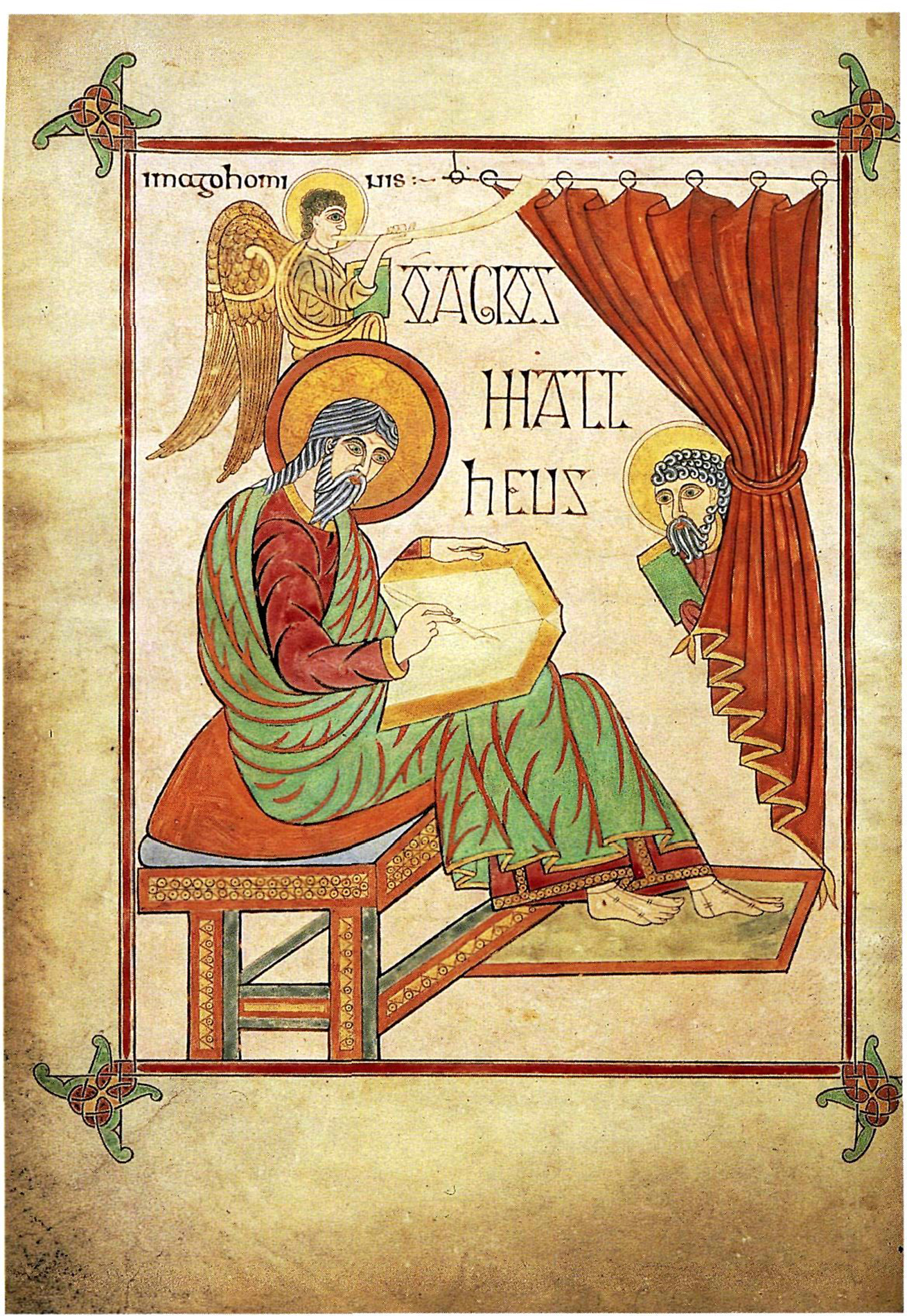

A portrait of St Matthew from theBook of Lindisfarneshowing the Mediterranean influence on manuscript art

A portrait of St Matthew from theBook of Lindisfarneshowing the Mediterranean influence on manuscript art.

Aidans monks also brought the traditions of their Celtic church, including gospels that pre-dated St Jeromes Vulgate, his fourth-century translation from original texts. Any attempt to date the Book of Kells must account for the extent to which its text varies from both the Vulgate and other Celtic gospels.

Another clue to the Book of Kells date lies in the fact that it contains a greater variety of elements than any of the other Insular manuscripts mentioned above. All the main strands of Celtic illumination can be found in its pages. In abstract patterns alone, there are diverging and interlocking spirals that spring from indigenous Celtic decorations, interlocking ribbons perhaps derived from everyday, three-dimensional examples such as torques of braided wires, and frets, probably Mediterranean in origin, but with the Celtic addition of 45-degree angles.

Animal heads, legs and tails, added to the extremities of letters, appeared early in Insular manuscripts, but leaf patterns are seldom seen before about 800. They probably grew more from the habit of ornamenting animal tails with feathers that gradually took on the appearance of leaves, rather than from conscious imitation of continental examples. Both are present in the Book of Kells along with the addition of animal heads to interlace, a feature which first appears in the

Next page

Frontispiece: The Eagle, symbol of St John, from the Book of Kelts

Frontispiece: The Eagle, symbol of St John, from the Book of Kelts Carpet-cross from the Book of Lindisfarne (c 695) decorated with interlace in the Celtic tradition.

Carpet-cross from the Book of Lindisfarne (c 695) decorated with interlace in the Celtic tradition.  Carpet-page facing the beginning of the gospel of St John from the Book of Durrow (c 680). Note the intricate animal and serpentine interlace. Carpet-pages are purely ornamental, often with reversible designs which can be viewed either way up.

Carpet-page facing the beginning of the gospel of St John from the Book of Durrow (c 680). Note the intricate animal and serpentine interlace. Carpet-pages are purely ornamental, often with reversible designs which can be viewed either way up.  A portrait of St Matthew from theBook of Lindisfarneshowing the Mediterranean influence on manuscript art.

A portrait of St Matthew from theBook of Lindisfarneshowing the Mediterranean influence on manuscript art.