ALSO BY WADE ROWLAND:

Spirit of the Web: The Age of Information from Telegraph to Internet

Ockhams Razor: A Search for Wonder in an Age of Doubt

Galileos Mistake: A New Look at the Epic Confrontation Between Galileo and the Church

Copyright 2005, 2006, 2012 by Wade Rowland

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any

manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the

case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be

addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street,

11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

First published in Canada by Thomas Allen Publishers, a division

of Thomas Allen & Son, Limited.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts

for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes.

Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the

Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street,

11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.,

a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-348-5

Printed in the United States of America

To the memory of David F. Noble,

scholar and gentleman,

friend and mentor

The greatest task before civilization at present is to make machines what they ought to be, the slaves instead of the masters of men.

Havelock Ellis

The corporation is a machine for making money.

Anon

Acknowledgments

Much of the initial research for this book was done while I was Maclean Hunter Chair of Ethics in Media at Ryerson University in Toronto. I am grateful to the Ryerson School of Journalism and its faculty for the opportunity to teach and do research for two years in a field in which I have an abiding interest, and to the many students who helped me hone my ideas. Since then, I have been teaching courses based on themes explored in this book to both graduate and undergraduate communication studies students at York University in Toronto, where once again interactions with students and faculty colleagues have helped in the further development of my ideas. I am also indebted to my Canadian editor and publisher, Patrick Crean, and to the late, legendary Richard Seaver, my American publisher at Arcade, for their interest in and support for my somewhat unorthodox take on the world. My wife, Christine Collie Rowland, provided sound editorial advice, as always. And finally, I want to thank my editors at Skyhorse, Jennifer McCartney and Ruoxi Chen, who saw the need for this revised and updated edition of the book.

Introduction

Protests come and protests go. Sometimes, rarely, they morph into the kind of social movement that can change history. When I briefly attended the Occupy Wall St. gathering at Zuccotti Park on lower Manhattan in late October, 2011, there was no way of knowing whether or not it had legs. The Arab Spring was in full bloom, and the Occupy movement, which had quickly spread to scores of cities around the world, took some inspiration from it. But the young people in Tahrir Square in Cairo and in the bloodied streets of Tunis and Benghazi had been playing for keeps, with real bullets and real corpses. And what they were fighting for was as clear as it could be; they wanted to get rid of dictatorships and establish democracy and the rule of law. They wanted a future.

The Occupy movement, like the Global Justice movement that preceded it, had less iconic, less obviously heroic goals. It did, however, share the craving for a future in which an ordinary person could get an even break. A longing for justice and equity was at the heart of its We are the ninety-nine percent slogan. The media at first ignored it, then ridiculed it, then lavished attention on it. President Barack Obama expressed some sympathy. Fox News hysterically (in both senses) reported an apocalyptic left-wing conspiracy, a red army of radicals seeking no less than to provoke a new, definitive economic crisis, with their goal being the full collapse of the U.S. financial system, with the ensuing chaos to be rebuilt into a utopian socialist vision. But no one could figure out exactly what was being demanded, not even, apparently, the protestors.

When I was in Zuccotti Park there a young man who showed signs of sleeping rough for several days carried a placard asking: Are We Really Going to Let a Bunch of Greedy Selfish Fools Rule This Whole Planet? A couple of days later, in Toronto, where things tend to be less in-your-face, a trimly-bearded man with leather patches on his sweater sleeves carried a hand-lettered sign that complained: I was told to expect cake. But it was another Zuccotti Park sign which best summed up the protest in its early, amorphous days. Scrawled in black marker on what appeared to be a brown paper bag, it read simply: WTF?

It was a deft synopsis of the confusion, helplessness, and outrage of the sixty-two million Americans suddenly left with zero or negative net worth following the sub-prime bubble of 2008; the 9.3 million adult workers who were jobless; the twenty-five percent of teens who couldnt find work. While they tried to cope, and to keep a roof over their heads, the handful of bankers and hedge fund managers whod caused the mess were busily socking away billions in government bailouts and performance bonuses. In the face of this scandal, government seemed powerless, useless, locked in a corporate-sponsored political cage match in Washington. Things were no better across most of Europe, where protests tended to be even bigger, and more militant. The fury there against banks and other financial institutions was white hot.

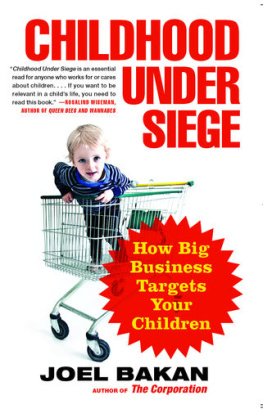

Matt Taibbi, who earlier in the year had deliciously described Goldman Sachs as a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money, worried in Rolling Stone that month that the protest might fizzle if it didnt come up with some concrete demands. My own hope was that it might eventually focus on an idea abroad in New York and European capitals, that it was time to take a serious look at the sources of power of the enormous corporations that today rule the world in a very literal sense. Some speakers were even calling for a law to repeal the privilege of personhood bestowed in suspicious circumstances on corporate America in the nineteenth century, and since then leveraged into near-invincibility worldwide. Banks and other financial corporations were a particular target, and the chant, End the dictatorship of finance, was beginning to be heard. Journalist and author Chris Hedges was an eloquent spokesman when mainstream media called on him to explain what was going on. The protestors, he said:

want to reverse the corporate coup thats taken place in the United States and rendered the citizenry impotent. Those who are protesting the rise of the corporate state are the true conservatives, who are calling for the restoration of the rule of law. The radicals have seized power and they have trashed all regulation and legal impediments to a reconfiguration of American society into a form of neo-feudalism. And thats what were really asking forthe restoration of the rule of law.

And as Halloween approached, confirmation of the extent of income disparity in the United States was supplied by the Congressional Budget Office in a massive study that showed that while median income of American households had grown by about forty percent over the past thirty years, the income of the top one percent soared by more than 280 percent. Income among the poorest ten percent had virtually flat-lined over that time. The gap between the richest and poorest in the U.S. more closely matches that of Uruguay, Jamaica and many emerging African nations than that of Northern European countries such as Norway and Germany.

Next page