I have long yearned for a New Testament that would put first books firstthat would sequence the books of the New Testament in the chronological order in which they were written rather than in the order in which they appear in the New Testament familiar to Christians.

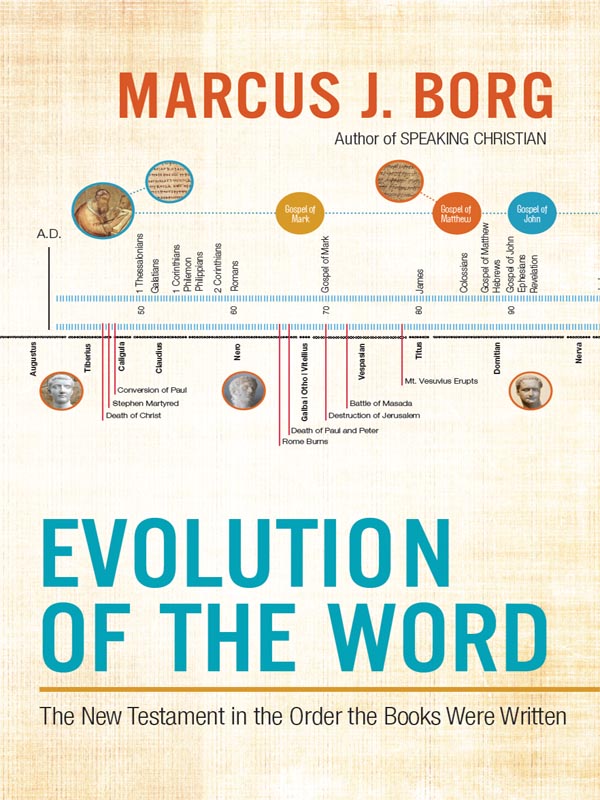

Scholars have known for a long time that the canonical sequence of the New Testament is not the same as its chronological sequence. The earliest documents are not the gospels, but at least seven of the letters of Paul, written in the 50s. The gospels come later, beginning around the year 70. And though Revelation ends the canonical New Testament, it was not the last to be written. That distinction almost certainly belongs to the second letter of Peterand others are also later than Revelation.

I can still remember my surprise long ago when I learned that the first things written about Jesus and early Christianity were in the letters of Paul and not in the gospels. Since then I have heard and read a lot about all this and have tried to explain it to others, but fear that it probably sounds abstract and is soon forgotten.

I wish a seminary professor had shown me a first books first New Testament and that Id had copies to show and tell and sell throughout my ministry. Presenting the book and having people young and old hold it in their hands and look at it would teach more than hundreds of words about dates and authorship.

If I were still a parish pastor, Id hand out copies to all my Confirmation students and say, Heres a different New Testament. You have never seen one like it. Take a good look at it and then tell me how its different.

In a few minutes they would learn something that they had never thought of before and that many would never forget. We would spend the class thinking about how this can help us understand the New Testament. At the end of the class, Id ask them to take this strange new New Testament home to show their families, asking them, How is it different? If they couldnt figure it out, the confirmands were to tell their families what they had learned in class that day.

Id do something similar with adult Bible studies and forums. I would encourage members to buy a copy, read the New Testament in this chronological order, ponder the introductions, and join a group to share and discuss their experience of reading this New Testament with others.

I think every pastor, seminary professor, and seminary student should have a copy of this chronological New Testament. And every congregation should have a stack for purposes of show and tell and sell. It will change the way we see the emergence and development of earliest Christianity. It will be an adventure of exploration and discovery.

Bishop Lowell Erdahl

Evangelical Lutheran Church of America

The Evolution of the Word

This chronological New Testament is the same as and yet different from the canonical New Testament. It contains the same twenty-seven documents, but it puts them in the order in which they were written.

The gospels do not come first. Rather, seven letters written by Paul do. Revelation is not at the end. Second Peter is, and eight other documents are later than Revelation.

Seeing the documents of the New Testament in chronological sequence illustrates and demonstrates a central theme of this book, namely, that the Wordshorthand for the Word of Godevolved. By evolved, I mean simply that it developed and grew over time.

For Christians, the Word of God refers to both a book and a person. As a book, it includes both the Old and New Testaments. Though Christians have often (and wrongly) thought of the Old Testament as having inferior status, it does not cease to be the Word of God because of the New Testament. Rather, the New Testament is an evolution, a development, that does not leave the old behind.

The Word of God as the Bible evolved over a period of a thousand years. Most biblical scholars date the earliest written parts of the Old Testament to the 900s BCE and the latest parts of the New Testament to the 100s CE .

The Word of God as a person refers of course to Jesus. He is the Word made flesh, incarnate, embodied in a human life. Of course, he himself evolvedfrom childhood into early adulthood and into and through his public activity. But alsoand this is what a chronological New Testament illustratesunderstandings of his significance and meaning evolved, developed, in the decades and century after his historical life. The Word as book and as person is not static, but the product of a process.

The process, however, is not intrinsically about improvement. Later does not always mean better. Rather, as we will see, some of the later documents in the New Testament reflect a domestication of the radicalism of Jesus and early communities of his followers.

Canonical New Testament and Chronological New Testament

The canonical New Testament (in other words, the official ordering of the books in church Bibles) begins with the gospels and concludes with Revelation. Because Jesus is the central figure of Christianity, it makes sense that the New Testament begins with narratives of his life, teachings, and passion. Thus the gospels are chronologically first in a biographical sense. And because Revelation is about the last things and the second coming of Jesus, it makes sense that it comes at the end. Revelation and the gospels function as bookends for the New Testament; everything else comes in between.

By putting these documents in a quite different sequence, namely, the order in which they were written, this book presents a literary chronologya panoramic view of how the ideas and stories of the New Testament changed over time. It also emphasizes chronology in a second important sense, namely, that of seeing, reading, and hearing these documents in their historical context, the world of the first century and a bit beyond.

Both of these emphases are the product of modern biblical scholarship. Its roots go back to the birth of modern thought in the Enlightenment of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Though the Enlightenment began with science (Copernicus, Galileo, Newton, and so forth), it soon extended to other areas of inquiry, including the study of the past. It generated a historical approach to the Bible and early Christianity that emphasizes the importance of seeing its documents in their ancient settings. When were they written? What were the historical circumstances in which they were written? What did they mean in their ancient context?

This historical approach to the Bible and the New Testament is not universally embraced by Christians. Those in churches committed to biblical inerrancy and a literal interpretation of the Bible reject much historical scholarship, because it calls into question their understanding of the Bible as having a divine guarantee to be factually and absolutely true. Some Christians are unaware of the historical approach and thus neither reject nor affirm it. But it is taught in most universities and colleges and in mainline Protestant and Catholic seminaries.

Though modern biblical scholarship has not led to unanimity about how to sequence all of the New Testament, there is a consensus about a basic chronological framework:

- The earliest documents are seven of the thirteen letters attributed to Paul. There is universal agreement that these seven were written by Paul in the 50s. They are earlier than the gospels.

- The first gospel is Mark, written around the year 70. Matthew and Luke both used Mark when they later wrote their own gospels.