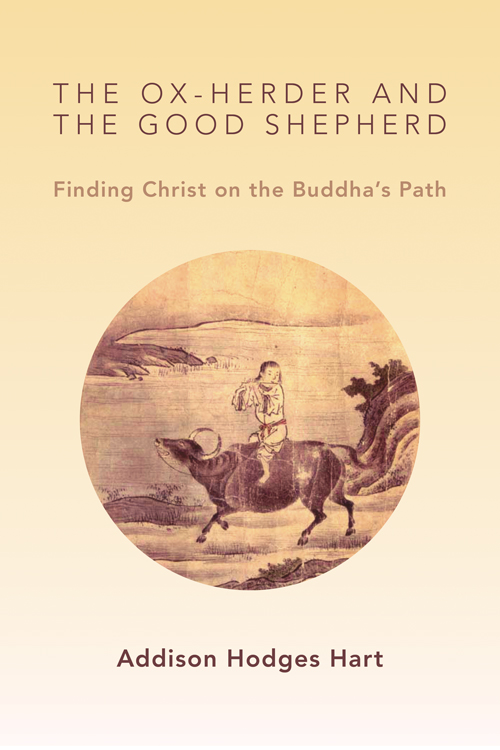

The Ox-Herder and the Good Shepherd

Finding Christ on the Buddhas Path

Addison Hodges Hart

William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company

Grand Rapids, Michigan / Cambridge, U.K.

2013 Addison Hodges Hart

All rights reserved

Published 2013 by

Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

2140 Oak Industrial Drive N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49505 /

P.O. Box 163, Cambridge CB3 9PU U.K.

www.eerdmans.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hart, Addison Hodges, 1956

The Ox-Herder and the Good Shepherd: Finding Christ on the Buddhas Path / Addison Hodges Hart.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8028-6758-2 (pbk.: alk. paper); 978-1-4674-3898-8 (ePub); 978-1-4674-3857-5 (Kindle)

1. Jesus ChristBuddhist interpretations. 2. Kuoan, 12th cent. Shi niu tu song. 3. Christianity and other religionsZen Buddhism. 4. Zen BuddhismRelationsChristianity. I. Title.

Unless otherwise noted, the Scripture quotations in this publication are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyrighted 1946, 1952 1971, 1973 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the U.S.A., and used by permission.

For

SISTER CATHERINE GRACE OF ALL SAINTS,

my first teacher in contemplative prayer

Contents

T he Christian by definition is someone who is interiorly free.

That is to say, he or she is free to search out everything that leads towards the truthwhether its the truth about the source and sustainer of all being which we call God and have seen revealed in Jesus Christ, or the truths about this impermanent world and the unfolding creation, or the truths we find within our selvestruths both good and not so good.

Wherever truth is to be found, we are free to search for it.

A Christian should never be fearful of the location of truth. Even when its in other faiths, other philosophies, history, or science, its still truth; and if its true, it is to be trusted. All truth is Gods. There cant be anything alien or threatening in it. The Christian who dreads the discovery of any truth, no matter where its found and even if it overturns cherished presuppositions, or who denies that truth is everywhere and always present, fundamentally denies that God is the one in [whom] we live and move and have our being, and that all human beings of every time and place are indeed his offspring (Acts 17:28). The Christian may seek to make Christ better known wherever he or she is (which is always best served by actions and attitudes, not by arguments and aggressiveness), but no Christian is free to deny the traces of truth that often lie right underfoot.

Not only is the Christian free to seek truth outside the confines of Bible and church (not that there really is an outside, since all truths are really already in God), but the Christian can even draw on the various sources of wisdom that have flowed into and through human minds universally. An old, frequently forgotten Christian principle has been that we should not fear to bring the riches of perennial wisdom into the church. Thoughtful Christians have always recognized that the logos meaning word, reason, and messagewas revealed before Jesus embodied it in himself. It was synonymous with the common universal wisdom traceable throughout the history of the race and present in every human culture. The great Latin church father Augustine, for example, wrote in his Retractions (I.13.3) that that which today is called the Christian religion existed among the ancients, and has never ceased to exist from the origin of the human race, until the time when Christ himself came, and men began to call Christian the true religion which already existed beforehand. For Augustine, as for all the greatest Christian thinkers down the ages, wisdom is tapped from many living veinsand it has run through the ages of humankind like the blood that circulates in the human body or like the rivers that flow on the earth and sustain life. The essence of the perennial logos of God has given spiritual life and health to the human intellect since its inception.

When Christians become nervous about protecting the uniqueness of Christianity among the worlds religions, they need to pause and consider that it isnt uniqueness at all that they wish to protect. Its the superiority of Christianity they really want to assert, and thats quite another matter. After all, everything, and certainly every form of belief, is unique. Buddhism, for instance, is every bit as unique as Christianity, and Buddha is every bit as unique as Christ. The real issue for Christians is not uniqueness, but superiority, orput differentlywhich faith is right (and, of course, which ones must therefore be wrong).

My own thoughts on this are simple, but unsatisfactory to many; but Ill stick with them regardless of that. They are these. Jesus himself shows absolutely no interest and makes no assertions about either uniqueness or superiority. He assumes that his message of the kingdom of God is powerful and attractive, and he draws disciples to himself whom he teaches to observe his way of living in the world. By word and deed they are meant to witness to the truth of Jesus words, life, cross, and resurrection, and reveal by their love and peacefulness a community oriented towards God. They are not meant to argue about God, but meant to show forth God. Superiority is simply not part of the message, and uniqueness is simply an indisputable fact. To the same extent that Christians have been true or false to Jesus way, those of other beliefs (or no beliefs) will weigh its truth and value. The proof, as they say, is in the pudding. Christians who assert superiority might take note.

All thats been stated so far has been my own understanding of the Christian mind and Christian freedom for as long as I can remember. I confess here at the outset that I believe, and always have, that the Christian faith has nothing to fear from dialogue with the other great faiths and philosophies of humankind. Marked differences and spiritual and human commonality exist simultaneously between religions. I choose to focus more on the commonality than on the differences, and leave the rest to God.

Huston Smith has suggested that human beings share, as it were, a common religious grammar. From the human person outward towards infinity we discover a shared vision of hierarchies and levels of reality; within the human person we find a common experience and a perception of depths capable of profound spiritual transformation. All the worlds faiths reproduce this common grammar of spiritual experience and perception in one way or another.

As I said above, the classical Christian view (or at least one significant version of it) has been to recognize the divine logos as shaping this common grammar in a hidden way, and revealing itself definitively in the person of Jesus Christ. Even if those of non-Christian faiths dont perceive that to be the case, we Christians nevertheless can. If we think about it sufficiently long and hard enough (and assuming we have really encountered the pertinent texts and traditions firsthand and on their own terms, without prejudice or hubris), why shouldnt a Christian discern Christ and God, say, in the concept of the Tao, or in the words of Krishna to Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita, or in the notion of the Buddha nature? This may even be one more way of understanding how Christ is before all things, and in him all things hold together (Col. 1:17). Christians who seek to be followers of the way of Jesus should seek to live peaceably with all (Rom. 12:18), and perhaps the tacit recognition of Christ already at work in all faiths is a path towards achieving that. Im certainly not the first to express such a view, but it bears repetition.

Next page