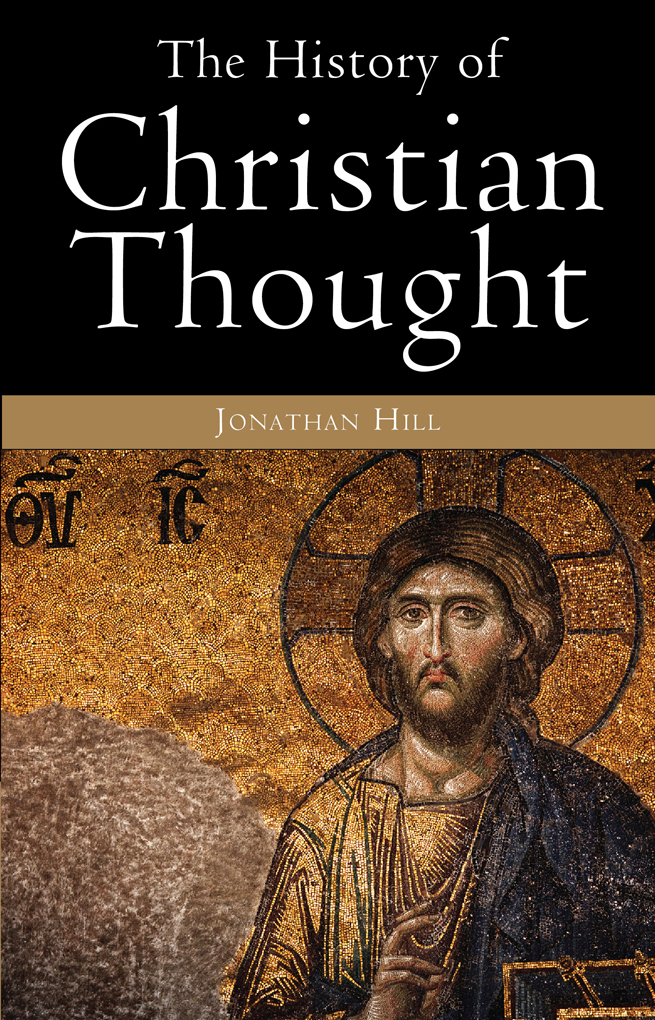

Text copyright 2003 Jonathan Hill

This edition copyright 2003 Jonathan Hill

The right of Jonathan Hill to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Published by Lion Books

an imprint of

Lion Hudson plc

Wilkinson House, Jordan Hill Road,

Oxford OX2 8DR, England

www.lionhudson.com/lion

ISBN 978 0 7459 5093 8

e-ISBN 978 0 7459 5763 0

First edition 2003

First electronic edition 2013

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

Cover image: THEPALMER/iStock

Contents

Introduction

Many readers will perhaps be puzzled by the appearance of a book with this title. What exactly is Christian thought? And why should we be bothered about its history? We might think, after all, that most Christian doctrine is to be found in the Bible, especially the New Testament, and that all Christian writers have ever done is explain it to their contemporaries. Why study the ways in which they explained it in the past?

In fact, the study of the history of Christian thought is both important and fascinating in its own right. If you are a Christian yourself, then you should certainly be interested in why Christianity teaches the things that it does. It may be true that the essentials of Christianity are taught in the New Testament, but the way in which we read the New Testament today is the product of centuries of speculation and development. And the thought of those who have reflected on Christian faith in the past remains a treasury of inspiration to those doing the same thing now.

Even if you are not religious, the history of Christian thought is well worth knowing about, just like any other important historical subject. People like Augustine, Aquinas and Luther have shaped the very fabric of modern society. Even if many people no longer believe what they did, we are still, most of us, the heirs of the Church Fathers and the medievals; and because Christianity has spread across the globe, from South America to Japan, from Siberia to New Zealand, that is not just true of Europeans. And this is quite apart from the inherent interest of the subject many Christian writers lived through some of the most turbulent or exciting periods in history, even playing a leading role in those periods, and some of the things they said are worth hearing whatever your own religious beliefs.

This book offers an introduction to the history of Christian thought for the completely uninitiated. I have assumed no knowledge in the reader of the people involved or the subjects about which they wrote, and I have aimed to avoid all the unpleasant technical jargon with which this subject, like every subject, tends to surround itself. There is also a glossary.

The study of Christian thought its nature, its development and its content is the study of theology; and the study of theology inevitably involves dealing, in one way or another, with theologians. If someone is called a theologian, that means one of two things: either they are someone who studies theology, like a historian studies history; or they are someone who actually contributes to it someone who reflects on what the Christian faith means to them and who writes it down in a more or less systematic way.

This book is largely the story of theologians in the second sense: the people who have made the history of Christian thought what it is. It focuses on their lives as well as their works. On the one hand, of course, we cannot really understand what they said if we do not know the context in which they said it; but on the other, their lives have often been as colourful and as inspiring as their writings. My aim has been to bring their personalities to life in a way that will help to show why they said the things that they said, and to show why we should still care about them today.

In order to do this, I have looked at the issues that confronted the great theologians of the past, and the ways in which they dealt with them. Of course, many of the issues that they faced were each other, and so I have aimed to provide a sense of narrative and progression and show that many theologians were tackling problems, or developing ideas, first raised by their predecessors. The constraints of space and need for clarity have meant that I generally focus on just the most important or relevant areas of peoples thought, rather than attempting to give a comprehensive account of everything that they said.

My goal throughout the book has been twofold. First, it has been to help the reader to understand and sympathize with the characters in the book even when disagreeing vehemently with what they said. If we can hope to understand properly what someone said, and why they said it, then it is no great impoliteness if we choose to disagree with them.

Second, I have encouraged the reader to go beyond the claims of the great theologians. Throughout the book I present constructive criticism of the theologians under discussion, partly to explain their thought in a little more detail, and partly as a springboard into more general considerations of the issues at hand. The reflections that I offer are intended to help readers to think about those issues for themselves; I have sought to present them in as unbiased and objective a way as possible.

The main narrative of the book describes the theologians their lives and their thought and major movements in Christian thought, in approximately chronological order. The boxes that accompany the main text provide additional information on events, places and movements that do not quite fit into the main narrative but are relevant to it.

The book is divided into six parts, each dealing with one of the great ages of Christianity. In a work of this scope, it has not been possible to include every Christian theologian or movement of the past 2,000 years, although I have tried to be as even-handed as possible. As a general rule, I have included those figures whose contribution to Christian thought was especially original, or especially influential.

In particular, I begin not with Jesus himself or the New Testament but with the developments that arose immediately afterwards. The origins of Christianity is a fascinating subject but one that is far too large and complex to address in this book. I have assumed that most readers will be roughly familiar with who Jesus was and what the New Testament says about him; for those who are not, there is a bit of catching up to do, and there are many books available to help!

The attentive will notice that I have taken the 20th century separately from the modern era. That is not to say that I necessarily think we are living in a postmodern age, but simply that the issues that theologians faced in the 20th century, and the answers they gave to them, were indeed quite different from those of the two centuries that came before.

Part

The Church Fathers

Our story begins at the height of the Roman empire. By the middle of the 2nd century ad, the mighty empire stretched from Britain to Palestine, from Germany to North Africa. Millions bowed to the seemingly eternal power of Rome. Yet the empire was more fragile than it seemed. After the 2nd century, its borders were no longer expanding. They were contracting, pushed back by wave after wave of invaders from the north and east: the barbarians. Racked by internal division, feuding emperors and a general sense of malaise, the Roman empire was about to enter a long but terminal decline.

Next page