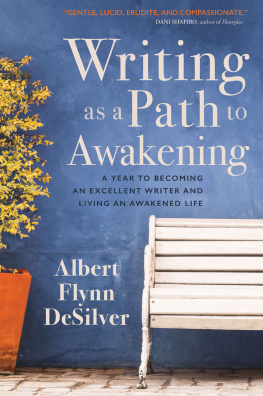

Praise for Karen Herings Writing to Wake the Soul

In this powerful, lovely, practical, and provocative book, Karen Hering offers the world both a new form of ministry that transcends multiple traditional boundaries and profound evidence that the asking of unanswerable questions brings forth wide-open spiritual narratives of astonishing depth.

Mary Farrell Bednarowski , professor emerita of religious studies, United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities

So many of us want to write! Writing satisfies some profound longingto become more fully ourselves, to connect more deeply to loved ones, to help transform our hurting world. In Writing to Wake the Soul , Karen Hering gives us the tools to act; our faith in writing can lead to a trustworthy spiritual practice.

Elizabeth Jarrett Andrew , author of Writing the Sacred Journey and On the Threshold

My soul yearns for a time when I can do contemplative writing. Having a guide to engage in such writing is an immensely precious gift that Karen Hering has given us. Elegant, accessible, and poetically imaginative, Writing to Wake the Soul is a great companion to have in ones spiritual journey. Dont go without it!

Eleazar S. Fernandez , author of Burning Center, Porous Borders

This is one of the best books ever written about the relationship between writing and spirituality. Karen Hering offers readers a wise and generous guide to mining essential material and transforming it into writing that is authentic and revelatory. Those who approach this book with open heart and mind will discover much about themselves.

Bart Schneider , author of Blue Bossa and Beautiful Inez

Karen Herings invaluable guide, Writing to Wake the Soul , brings alive the venerable art of writing as a spiritual practice for our time and place. It will awaken you to your own spiritual inclinations, as well as introduce you to a wealth of wisdom handed on by pilgrims who have preceded you on the way.

Donald Ottenhoff , executive director of Collegeville Institute for Ecumenical and Cultural Research

Profound in its clarity and completeness, here is a contemplative guide to awaken the nurturing spirit in each of us. Like a good guide, this book will take you by the hand as you journey, but only long enough to help you discover the compass and spiritual grounding you already carry within.

William C. Moyers , author of Broken

In Writing to Wake the Soul , Karen Hering has given us a spiritual practice that helps us tell our own stories while listening more deeply to those of others. This is important and healing work, and Herings book invites and equips us to participate in it. Its a book I plan to use myself, alone, and with others. Will be especially helpful in respectfully addressing sensitive issues such as sexism and racism.

Jonathan Odell, author of The Healing

Karen Hering is a wise and welcome spirit guide. From hints on quieting the inner critic to generous insistence that everyone is a writer, Writing to Wake the Soul invites private devotional practice. It will also awaken discussion between people of various faith backgrounds and those with no formal tradition at all.

Rev. Victoria Safford, senior minister, White Bear UU Church and author of Walking Toward Morning

Thank you for downloading this Atria Books eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Atria Books and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

C ONTENTS

For David and Cat:

you have added to my lifes unfinished sentences in beautifully surprising ways.

What is this precious love and laughter

Budding in our hearts?

It is the glorious sound

Of a soul waking up!

Hafiz

P REFACE

This is a book of sentences, some incomplete...

a book of narratives left open,

questions unanswered,

of theology still being written...

It is a book about words

but mostly about what pulses beneath them,

what stretches beyond all naming

between the lines,

off the page,

in the ellipses trailing after...

W hen I was a child, I wanted to be a missionary. Not a missionarys wife, I would explain with a four-year-olds insistence on being understood. I wanted to be the missionary. Years later, after my confirmation in a church where women were neither ordained nor present on the chancel during worship, I announced that I wished to serve as an acolyte, donning a white frock and ceremonially lighting the altar candles at the beginning of worship. It was 1972. The church elders took a vote on whether to permit my request and reported back to me that, like my sisters before me, I was welcome to serve in the nursery instead. Acolytes were male, they reiterated, their edict pinching off the possibilities of my story in the churchand the churchs narrative too.

The elders decision was a formative moment for me, though perhaps not in the way it was intended, for it revealed to me the inadequacy of closed narratives, of stories bound in predetermined endings and lacking in imagination and surprise. Their denial of my request marked the beginning of a personal practice of questioning that has served both my faith and my life well, for I soon discovered that closed narratives do not just occur in communities of faith nor are they only a matter of gender. We seal our narratives in tombs of expected outcomes all the time. We do this whenever we presume to know what can and cannot happen from the gridlocked standpoint of what is without ever asking what might be.

In my own story, the germ of my religious interests and vocation remained buried for many yearsfor decades, in fact, well into my adulthood and even after I joined a community of faith that had been ordaining women to the ministry for over a hundred years. Finally, in my forties, I enrolled in seminary. At first, I said I was a writer wanting to steep my words in theology. Then, as my studies continued, I realized I was a minister too. I wanted to be ordained but not to any form of ministry I had already seen or experienced. I wanted to bring writing and ministry together in a new way, and I was blessed to have a spiritual director (and a few seminary professors too) who patiently told me, as often as I needed to hear it, that perhaps the work I was called to did not yet exist and would not exist until I named it and brought it into being.

Slowly, I grew into that possibility. I came to understand that my vocation might best be described with a sentence not yet written. By the end of my seminary training, I realized I was not going to pursue a typical congregational ministry. Rather, I made up a job description for literary minister as a sketch of the ministry I thought I was meant to do. I knew I would be asked to describe and possibly defend it in the rigorous ordination examinations ahead of me, so I took the job description to the co-ministers of a large urban congregation in my denomination and asked them to help me find the faults in it. Instead, they asked how we might together find a way to develop such a ministry in their congregation. They too held the narrative open, as did the national foundation that funded the literary ministrys start-up; the individual donors who later supplemented the foundations grant; the congregation that housed and encouraged the new ministry of words and story; my husband and family, my ministerial mentor, my committee on ministry; and dozens of colleagues, friends, and other supporters who kept assuring me it was not folly to keep moving forward even though I could not say exactly where I was headed or whether the path would prove entirely passable.

Next page