T HE historian who sets out to cover more than three centuries in the life of a country must, of necessity, lean heavily upon his predecessors and colleagues, and the bibliography indicates the extent of my indebtedness to the published work of other scholars. Some more direct and personal obligations must be acknowledged here. Professor Michael Roberts read the book in typescript and Mr J. L. Lord, M.A., read it in proof; it owes more than I can easily calculate to their comment and criticism. I am indebted also to Dr R. E. Glasscock, and to the Geography Department of Queens University, for preparing the maps; to Mr David Kennedy, M. Sc, for the extract from the unpublished diary of John Black, quoted in Chapter VII; to Mrs Anthea Orr, of the Queens University History Department, who cheerfully undertook the laborious task of typing and re-typing the whole work.

Finally, I must confess that I entered upon the writing of this book almost by accident. I continued it, despite a growing conviction of my own incompetence, because I felt that the work should be done. My feelings on its completion can most appropriately be expressed in the words of that gentle and modest author, Izaak Walton: if I have prevented any abler person, I beg pardon of him, and my reader.

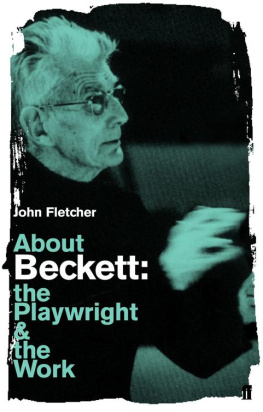

J. C. BECKETT

(1)

A n English civil servant of the sixteenth century, writing gloomily about the state of Ireland, found support for his pessimism in a proverb: It is a proverb of old date, that the pride of France, the treason of England, and the war of Ireland, shall never have end. Which proverb, touching the war of Ireland, is like alway to continue, without God set it in mens breasts to find some new remedy that never was found before. One reason why the year 1603 is so significant in Irish history is that then the war of Ireland was, for a time, ended, and the country entered on a period of unwonted peace, united for the first time under a central administration. It is true that the peace lasted hardly more than a generation, but it was long enough to give a new character to the political and economic life of the kingdom. The Ireland of the protestant ascendancy , out of which the Ireland of to-day has arisen, took form during the first four decades of the seventeenth century.

Though the peace and unity of 1603 were the outcome of Tudor policy, that policy was essentially defensive rather than aggressive: its great end was the safety of England, not the subjugation of Ireland. The Tudor sovereigns sought this end by many means: sober ways, politic drifts and amiable persuasions; flattery and fraud; repression and conciliation. It was only slowly and with reluctance that Elizabeth finally embarked on a war of conquest. But the shifting policies and varied expedients of the previous hundred years had left an inescapable legacy: the conquered Irelandthe Pacata Hiberniaof 1603 was the creation of the Tudors; and their influence went far to determine the character of the new Ireland that was to emerge under the rule of the Stuarts.

(2)

When Henry Tudor seized the crown in 1485 Ireland was still remote from the main currents of European life. Without either political strength or material resources to counter the influence of physical isolation, she lay, as it were, on the outer edge of the world, culturally no less than geographically ladivisadalmondoultimaIrlanda.Atone time a different development had seemed possible. In the twelfth century Henry IIs assumption of the lordship of Ireland had opened the prospect of an Anglo-Norman conquest, transforming the loose congeries of tribal kingdoms that constituted the Gaelic political system into a strong feudal state. But the conquerors were not numerous enough to colonize effectively the territories they had overrun; the English kings, absorbed in Scottish, French and Welsh wars, paid scant attention to their new province; the native Irish, at first overawed by the superior equipment and organization of their enemies, were able gradually to check and then to turn back the tide of conquest. The Bruce invasion in the early fourteenth century, though eventually defeated, hastened the decline of English influence and encouraged native resistance.

From this point, Irish politics assumed a pattern that was to survive until the reign of Elizabeth. The authority of the royal government, with its capital at Dublin, extended nominally over the whole country, but was effective only within a relatively small area, significantly referred to as the land of peace, the obedient shires, and, later, the English Pale. During the later middle ages it was this area alone that was regularly represented in parliament and contributed to parliamentary subsidies. In territories beyond the Pale, and especially in the towns, royal authority could sometimes be enforced and royal revenues sometimes collected; but the greater part of the country was divided into some fifty or sixty regions, each of which was virtually an independent state, ruled over by a native chief or r(king) or by an Anglo-Norman noble. By the fourteenth century many of the latter had adopted native names and customs and were hardly distinguishable from their Irish neighbours. Both native and Norman were ready, when interest or necessity impelled them, to make formal submission to the crown; but for the most part they lived as independent rulers, each one of whom, to quote a sixteenth century writer, maketh war and peace for himself and obeyeth to no other person, English or Irish, except only to such persons as may subdue him by the sword.

With little support from England, and with scanty resources of its own, the Dublin government had a hard struggle to maintain itself. Despite the effort made in the Statutes of Kilkenny (1366) to set a permanent barrier between the colonists and the native Irish, the Gaelic influence increased, and the Old English (to use the term by which the tended more and more to fall into the native way of life. The boundaries of the land of peace were gradually pushed back; by the end of the fifteenth century the Pale comprised only a narrow coastal strip, stretching from Dundalk to a few miles south of Dublin, and even this small area could with difficulty be defended against the depredations of the Irish.

Political instability and endemic warfare hampered the development of Irelands economy. There was no manufacture of importance, and agriculture was backward by contemporary English standards. Overseas trade brought prosperity to a few seaport towns, but was not extensive enough to produce a substantial middle class. The social and intellectual developments that in other parts of western Europe were linked with industrial and mercantile expansion had little effect on medieval Ireland. Nothing, perhaps, is more expressive of the poverty, backwardness and isolation of the country than the failure of all efforts to establish a university . The merchant and the university scholar were two of the agents by which the life of Europe was welded into a unity, and neither played much part in Irish society. It is true that the tradition of Gaelic learning was kept alive in the bardic schools and in some monastic houses; but the bardic schools had little or no contact with literary movements outside Ireland, and by the later middle ages the Gaelic tradition where it survived among the religious orders had become almost entirely self-contained .