St. Bonaventure University

St. Bonaventure, New York

All rights reserved.

No part of the book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Preface

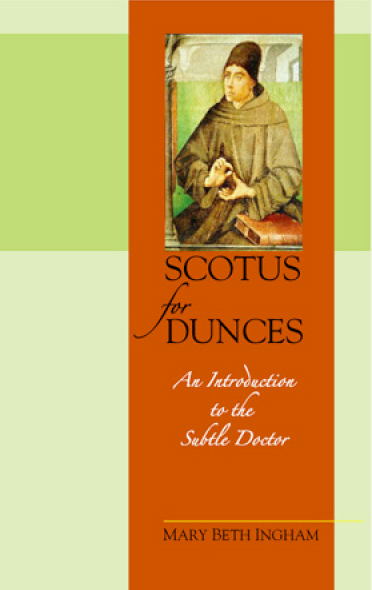

This English introduction to the thought of John Duns Scotus by Mary Beth Ingham is a most welcome text, filling as it does a definite need. After a well-written opening chapter on the life and literary works of the Subtle Doctor, the author arranges her presentation of Scotuss principal doctrines in three core chapters. Entitled Creation, Covenant and Communion, these chapters provide excellent insight into the work of Scotus and will be quite helpful to those seeking a point of entry into his complex thought.

Although Scotuss philosophy cannot be sharply separated from his theological concerns, the chapter on creation nevertheless contains those distinctive aspects of his thought that are most philosophical in nature. The chapter on the covenant, by contrast, is primarily theological, dealing with Scotuss belief that Christs incarnation was not primarily intended as a remedy of original sin, but intended for its own sake. Another chapter, Communion, deals with humanitys goal as sharing the inner life of love of the Blessed Trinity and how this influences our life on earth. The final chapter, Reading Scotus Today, shows not only the relevance but also the wisdom of rethinking the central human questions of our day in light of the assumptions that underlay Scotuss own solutions to these questions.

Not only does Ingham present these excellent thematic explications, she also provides appendices containing English versions of Scotuss writings, a wonderful resource for introducing readers to his literary style and profound thought. Gathered together in this way, they are a major contribution to academic discourse.

In a previous work, Ingham emphasized how an artistic paradigm colors the thought of Scotus: the notion of beauty as a moral category runs like a leitmotif throughout his ethics. Without abandoning that perspective, she now reveals how another significant aspect of the subtle Duns - namely, his Franciscan ideals - unifies his seemingly random distinctive ideas.

After reading Scotus for Dunces: An Introduction to the Subtle Doctor , one better appreciates why Pope Paul VI once wrote in Alma Parens : Saint Francis of Assisis most beautiful ideal of perfection and ardor of Seraphic Spirit are embedded in the work of Scotus and inflame it.

Allan B. Wolter, O.F.M.

Professor Emeritus

St. Anthony Friary

St. Louis, Missouri

April, 2003

Introduction

This book offers a basic introduction to the thought of Franciscan philosopher-theologian, John Duns Scotus. Known to history as the Subtle Doctor, Scotus has a reputation for intricate and technical reasoning. He is generally acknowledged as a difficult thinker whose ideas are neither clearly set forth nor easily followed. Scotist thought is not widely known precisely because it is so difficult to access. Some may have an idea of his isolated insights, most notably his position on the divine reason for the Incarnation, but beyond this, few other than the small circle of scholars who have mastered the thought of this late thirteenth-century Franciscan would claim to know much about an overall vision.

This text, then, is meant to be a simple guide , that is, an introductory presentation of both the philosophical and theological aspects of Scotist thought. It is simple , because I do not expect the reader to have any specialized background information on medieval philosophy or theology, on Franciscan spirituality, or on any particular systematic element needed to study the thought of such a great medieval metaphysician. It is also simple , insofar as I present ordinary examples to explain the more intricate distinctions found in Scotist thought. It is, however, not simple insofar as Scotuss insights themselves could ever be simplified. Indeed, his vision of God, reality and our relationship to both is intricate and complex. It is not possible to introduce such a thinker by reducing his thought to a simplistic rendering. In what follows, points will, at times, be explained as much as is possible (or appropriate) and still fall short of the transparency that both the author and the reader might desire.

In undertaking this book, I had one central interest. Having been struck by the centrality of beauty as a moral category in Scotus, I wondered whether one might approach Scotist thought from an aesthetic interpretive angle. By taking as my starting point the centrality of beauty as key to Scotist thought, I was reminded of the aesthetic dimension in other medieval thinkers, especially men like Bonaventure. The traditions of late antiquity, influenced by Augustines Platonism and the mystical theology of Pseudo-Dionysius, fed the development of medieval philosophy and theology through the influential 12th century School of St. Victor. The Victorines kept alive this Platonic and (what we today call) Neoplatonic tradition, adding to it a love for cosmology and study of the natural world. Their legacy was central to the brilliant work of those men living in what we call the High Middle Ages (specifically the 13th and 14th centuries) when texts of Aristotle became known in the West. Key thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas, Bonaventure and Scotus lived and wrote in a period of history that was unparalleled in terms of the confluence of spiritual, intellectual, and cultural accomplishments.

As these factors came together for me, I reflected upon the specifically Franciscan dimension that lay behind this aesthetic approach. I concluded that Scotuss identity as a Franciscan might offer a more fruitful way to approach his notoriously difficult texts and, through them, to understand his thought in a more integrated manner. This would entail viewing his intellectual achievements as central to his spiritual vision, itself an integral part of his life. It would also entail an approach that must be more thematic than systematic.

Such an approach offers several advantages. First, it does not separate the domains of philosophy from theology as vastly different and opposing areas of study. Second, it does not separate the created from the uncreated order. That is, it respects the connection that Scotus himself affirms between human knowing of the created order and human knowing of God. Third, it takes seriously the identity of Scotus as a Franciscan friar, one who followed the vision of St. Francis in his life and who saw his intellectual speculation as part of a larger spiritual journey. Finally, it does not reduce the thought of such a great mind to the imposed categories of contemporary thought, whether as philosophy or theology. So often, when we study thinkers from past ages or from other cultures, we reduce their thought to our own categories of understanding, so that we might make sense of them. This is, of course, inevitable to some extent. My attempt here is to reduce this temptation to a minimum by looking at Scotus from a vantage point that is intrinsic to his identity (his Franciscanism) rather than a vantage point that I impose from my own historical perspective.