Edited by Neil L. Whitehead and Robin Wright

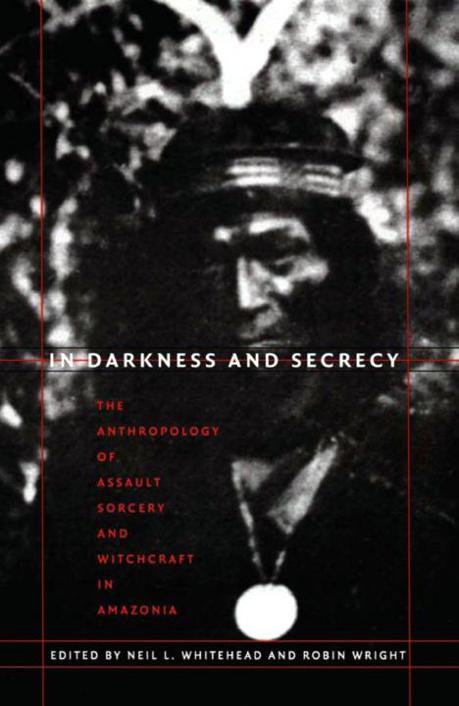

Shamanism is a burgeoning obsession for the urban middle classes around the globe. Its presentation in popular books, TV specials, and on the Internet is dominated by the presumed psychic and physical benefits that shamanic techniques can bring. This heightened interest has required a persistent purification of the ritual practices of those who inspire the feverish quest for personal meaning and fulfillment. Ironically, as Fausto points out in his essay in this volume, given the self-improvement motivations that have brought so many into a popular understanding of shamanism, two defining aspects of shamanism in Amazonia-blood (i.e., violence) and tobacco-have simply been erased from such representations (see also Lagrou, this volume). Such erasure is not only a vain self-deception but, more important, it is a recapitulation of colonial ways of knowing through both the denial of radical cultural difference and the refusal to think through its consequences. This volume is intended to counteract that temptation.

All of the authors whose works are presented herein are keenly aware of the way in which salacious and prurient imagery of native peoples has serviced the purposes of conquest and colonization over the past five hundred years. In missionary writings, for example, ideas about "native sorcery" and the collusion of shamans with "satanic" forces meant that such individuals were ferociously denounced and their ritual equipment and performances were banned from the settlement of the converts. In this context no distinction was made between the forms and purposes of ritual practice: curers as well as killers were equally persecuted. Thus, the rehabilitation of shamanism as a valid spiritual attitude and a culturally important institution that has taken place over the past twenty years through the enthusiastic, if ill informed, interest of the urban middle classes might be seen in a more positive light-that is, as rescuing a form of cultural variety that would otherwise be lost in the cultural homogeneity of globalization. Nonetheless, such a rehabilitation through a positive, almost cheery, presentation of the native shaman as psychic healer distorts the actual ritual practice of Amazonians and other native peoples in a number of ways, as the materials collected here will show. Moreover, the notion that shamanism should be "rehabilitated" in this way misses the important point that it is the supposed illegitimacy of shamanic practice that should be questioned, rather than trying to justify cultural difference merely through the possible benefits it might have for ourselves. Taking seriously cultural difference in this context means that we have also to ask what other reasons there were for the colonial desire to repress this particular facet of native culture. As the essays in this volume indicate, a large part of the answer to that question must be the very centrality of shamanic ritual power to the constitution of native society and culture, as well as the role that "shamans" thus played in resisting, ameliorating, and influencing the course of indigenous and colonial contacts and subsequent histories. The consequence of this issue must also be to recognize that shamanic idioms are still very much present in the exercise of political power from the local to the national levels and that this recognition makes an understanding of all aspects of such ritual action a fundamental project for an anthropology of the modern world.

What then is "shamanism"? Anthropological debate in Amazonia has considered whether or not the term describes a unitary phenomenon, and has persistently questioned its institutional existence and its presence as a defined social role (Campbell 1989; Hugh-Jones 1996; Fausto, Heckenberger, Pinto, this volume). Nonetheless, there is a utility to the term that has underwritten its persistence in the literature and its continuing adoption in the present. This utility consists in the fact that the performance of ritual specialists throughout Amazonia shows a number of resemblances that, although they do not represent a clear and distinct category of ritual action, nonetheless reveal ethnographically a variety of symbolic analogies and indications of historical relatedness. Moreover, native terms such as paj6 or piaii have passed easily from their original linguistic contexts into the mouths of many different speakers across Amazonia. Part of the reason for this may well be an apparent homogenization of ritual practice in the face of evangelism by Christian missionaries or other agents of colonial domination, but even if this were the only reason it would still be an important ethnographic fact about contemporary Amazonian cultures. Equally, anthropologists have tended to overlook or ignore the issue of violence. No doubt this is partly due to cultural prejudice against the exercise of violence, because it is held that its representation among others will only serve to lessen the authority and validity of their culture differences as something to be cherished and respected. Unfortunately, this has meant that we have not properly examined the "dark" side of shamanism, which is often integral to the efficacy of shamanism overall (Mentore, Santos-Granero, this volume).

The idea that shamanism thus expresses a recurrent moral ambiguity -for the same abilities that cure can also kill-recognizes a fundamental aspect of shamanic power through the presentation of shamanism as a personal or individual dilemma. However, shamanism's role in the reproduction of society and culture suggests that this view is incomplete and partial because it deals only with the appearance of shamanism in the routines of daily life. Indeed, in the case of the Parakana (Fausto, this volume) the dark associations of shamanism, its past connections to warfare, and the uncertainty as to the status of those who might claim to have shamanic powers, have all but occluded its light or curing aspects. The deep mytho- historical presence of dark shamanism, contemporary with, if not actually preceding, the original emergence of persons and shamanic techniques, indicates that dark and light, killing and curing, are complementary opposites-not antagonistic possibilities. In the same way that shamanism itself has been historically shaped by forces conceived of as external to the originating shamanic cosmologies, so too the ritual practices of curers are intimately linked to the assaults of shamanic killers and cannot be understood apart from them (see Heckenberger, this volume). The loci of these cosmological contests become the bodies, both physical and political, that are created and destroyed through the ritual-political actions of chiefs, warriors, and shamans.