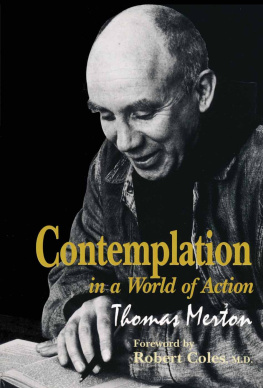

INTRODUCTION

If the deepest ground of my being is love, then

in that very love and nowhere else will I find

myself, the world, and my brother and sister

in Christ. It is not a question of either-or but

of all-in-one. It is not a matter of exclusivity

and purity but of wholeness, wholeheartedness,

unity, and of Meister Eckharts gleichheit

(equality) which finds the same ground of love

in everything.

THOMAS MERTON, Contemplation in a World of Action

***

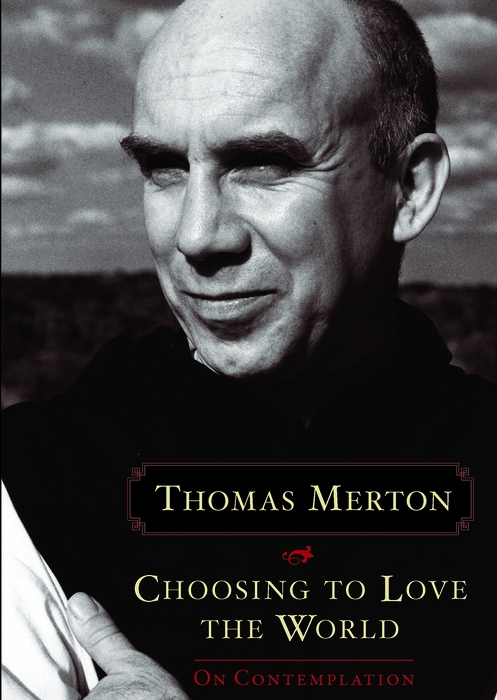

The American writer Thomas Merton (19151968), a monk of The Abbey of Gethsemani in Nelson County, Kentucky, for twenty-seven years, possessed an inclusive, un-walled spirit. Sorrowed by the wars of his time, he affiliated himself with his generation as it rode the waves of the twentieth centurys harshest flow of events. Whereas an older school of monastic observance warned monks to abandon the world as decisively as one flees a sinking ship, Mertons monastic project was a blend of world-engaging actions: he prayed, wrote books, and, as a mature monk, publicly protested any perspective that threatened the unity of all beings that was at the heart of what he believed real in human experience. Merton contributed to and loved what he conceived to be the worlds real history, the flow of events coproduced by the thought and action of each singular, potentially lovely, member of the one body that is our humankind.

Merton wrote in a variety of genres: poetry, meditative prose, the scholarly article, political polemic, dramatic pieces, song cycles, autobiography, and the personal letter and journal. He was among the first Roman Catholic American writers with a popular audience to share his enthusiasm for contemplative traditions other than his own. His reading in Buddhist, Islamist, Hindu, Jewish, Taoist, and Confucian traditions bore fruit in his personal contacts with an international spectrum of contemplatives and scholars of religion. Mertons influence continues to affect those committed to contemplative living and interfaith dialogue in the twenty-first century.

Educated in France and England, receiving his undergraduate and graduate degrees from Columbia University in New York City, Merton challenged the distorted perspectives of a monocultural approach to relationships. His contemplative life supported his lifes project to free himself and his neighbors from what he called the obligatory answers prescribed and enforced by their educations, their racial and national heritages, their religious tribes, and any of their institutions that thrived by dividing human beings into family and strangers.

In 1941, at the age of twenty-seven, Merton entered a rigorous discipline of personal transformation in a Trappist monastery, where strict rules programmed every aspect of its members daily lives. And yet this institutionalized life of prayer provided him with disciplines necessary for the inner work to transcend its narrow boundaries and free his religious imagination to view God as a limitless horizon. Merton taught his readers that true religion should always make them personally and communally free. In Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, one of his best books, as relevant today as ever, he wrote that true religion always nurtures freedom from domination, freedom to live ones own spiritual life, freedom to seek the highest truth, unabashed by any human pressure or any collective demand, the ability to say ones own yes and ones own no and not merely to echo the yes and the no of state, party, corporation, army or system. This is inseparable from authentic religion. It is one of the deepest and most fundamental needs of the human person, perhaps the deepest and most crucial need of the human person as such.

Merton never held the world at arms length. The world for him was more than a physical space traversed by jet planes and full of people running in all directions, offering a monk only one of two choices: to fight or flee. His world was no objective thing directed by impersonal forces that rendered humankind without liberty to act the way we act and live for what we live. For Merton, the world was always being reconfigured through a complex of responsibilities and options made out of the love, the hates, the fears, the joys, the hopes, the greed, the cruelty, the kindness, the faith, the trust, the suspicion of all.

Merton embraced monastic life as a protest against his own false self. He vowed himself to inner struggle against the ego-centered individualism embedded in his psyche. By becoming a monk, he hoped to marginalize himself from the mental geography of the impatient ones who conceived reality in terms of money, power, publicity, machines, business, political advantage, military strategywho seek the triumphant affirmation of their own will, their own power considered as the end for which they exist. Merton rarely minced words as he pierced through the patina of American innocence and idealism to confront the metallic hardness of its national greed, pride, and misdirected lust to be first in everything. But if his monastic life rendered him a marginal person to the dominant materialistic paradigm of American society, he never renounced his citizenship or his responsibility to put his whole self to work in shifting Americas priorities: Man has a responsibility to his own time, not as if he could seem to stand outside it and donate various spiritual and material benefits to it from a position of compassionate distance. Man has a responsibility to find himself where he is, in his own proper time and place, in the history to which he belongs and to which he must inevitably contribute either his response or his evasions, either truth and act, or mere slogan and gesture.

The biting criticisms of contemporary Western culture gathered in this book are balanced by those passages that reveal a poet of his inner experiences who was aware of his own fragile grasp on truth. Thus, in judging personal matters through which all human beings suffer, he was never fundamentalist. Admitting the complexity and the paradoxes attending his own life, he renounced an intellectuals obsession to nail every human ethical question to the floor. he was conscious of his need for lifelong learning to render himself better able to decipher the deeper subtexts of his own lifes and his worlds flow of events. his writing exhibits his constant attention to a diverse, mixed chorus of other voices. He exuded religious enthusiasm for tracking Gods presence in and for the world, a presence which he apprehended as profoundly personal. Mertons theology was lived: God surged in all our bloodstreams, within the stream of reality of life itself.

In all his writing, Merton characterizes the contemplative life as a life of relationships informed by love in search of freedom. We are the primary actors in the formation of our own identities. We create networks of nurturing interrelationships with our fellow human beings. We affect and are affected by the matrix of natures evolution within which we move and have our being. Through this trinity of relationships, we experience communion with the Source that underwrites our being in time, the