The publisher wishes to thank and acknowledge the editorial efforts of

Jeffrey Neilson and Robert Hass in bringing this book to print.

From the Monastery to the World

Introduction copyright 2017 by Robert Hass

The Letters of Ernesto Cardenal copyright 2017 by Ernesto Cardenal

English Translation and Afterword copyright 2017 by Jessie Sandoval

The letters of Thomas Merton are reprinted with permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc,

publishers of the books The Courage for Truth and Witness to Freedom , by Thomas Merton,

copyright 1993 and 1994, respectively, by the Merton Legacy Trust.

Excerpt from A Letter to Pablo Antonio Cuadra Concerning Giants by Thomas Merton,

from The Collected Poems of Thomas Merton , copyright 1963 by The Abbey of Gesthemani.

Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Selections from Gethsemani, KY

by Thomas Merton, original by Ernesto Cardenal, from The Collected Poems of Thomas Merton ,

copyright 1977 by The Trustees of the Merton Legacy Trust. Reprinted by permission

of New Directions Publishing Corp.

The letters of Thomas Merton and Ernesto Cardenal were first published in Spanish in

Del Monasterio al Mundo: Correspondencia entre Ernesto Cardenal y Thomas Merton (19591968) ,

copyright 2003 by Editorial Trotta, S.A., 2003, and copyright 2003 by Santiago Daydi-Tolson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sandoval, Jessie, editor. | Merton, Thomas, 19151968. Correspondence.

Selections. | Cardenal, Ernesto. Correspondence. Selections.

Title: From the monastery to the world : the letters of Thomas Merton and

Ernesto Cardenal / edited and translated by Jessie Sandoval ; with an introduction by

Robert Hass.

Description: Berkeley : Counterpoint, 2017. | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017015890 | ISBN 9781619029019 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Merton, Thomas, 19151968Correspondence. | Cardenal,

ErnestoCorrespondence.

Classification: LCC BX4705.M542 A4 2017 | DDC 271/.12502dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017015890

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by Publishers Group West

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Table of Contents

Introduction

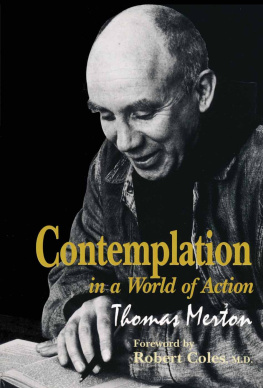

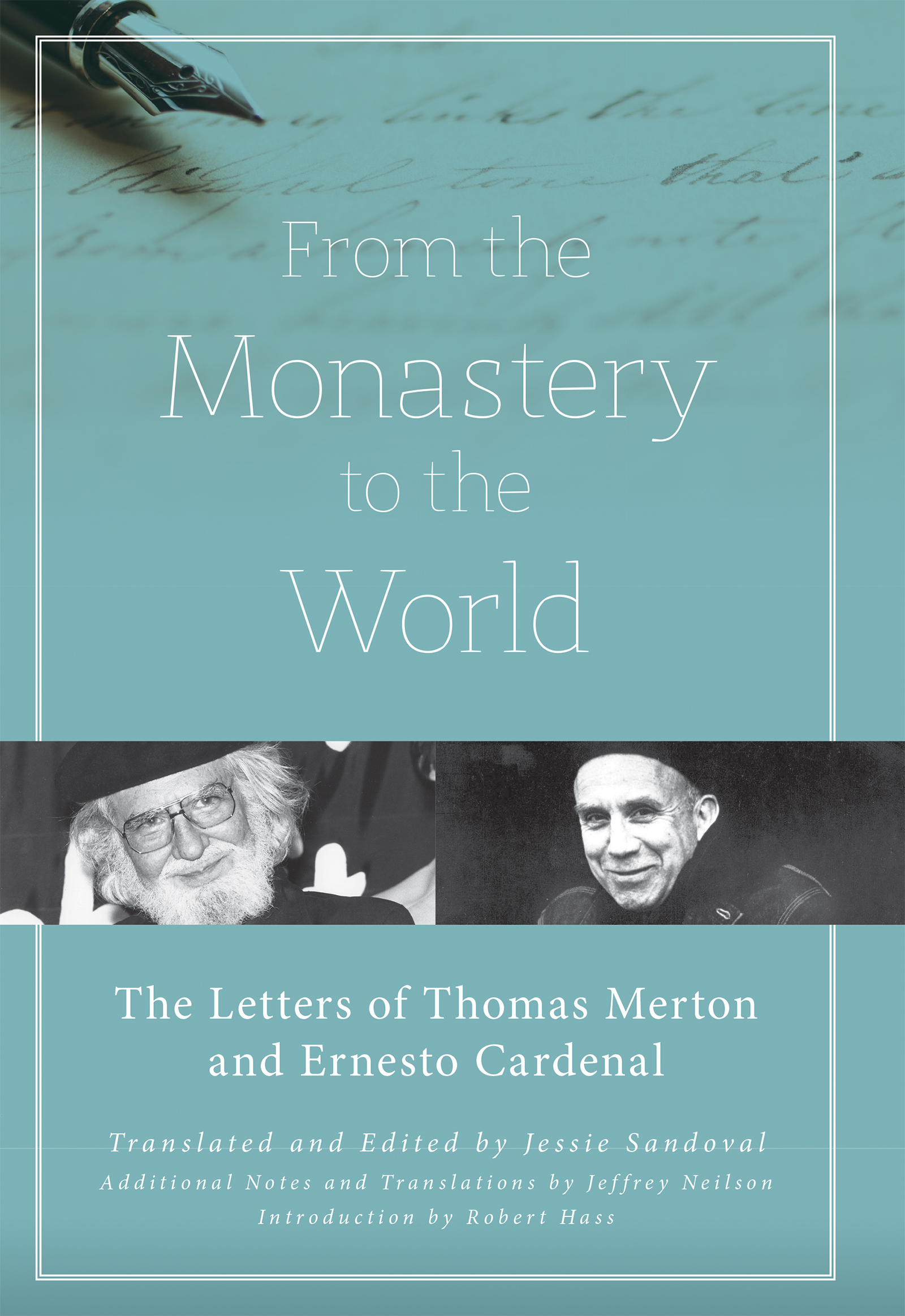

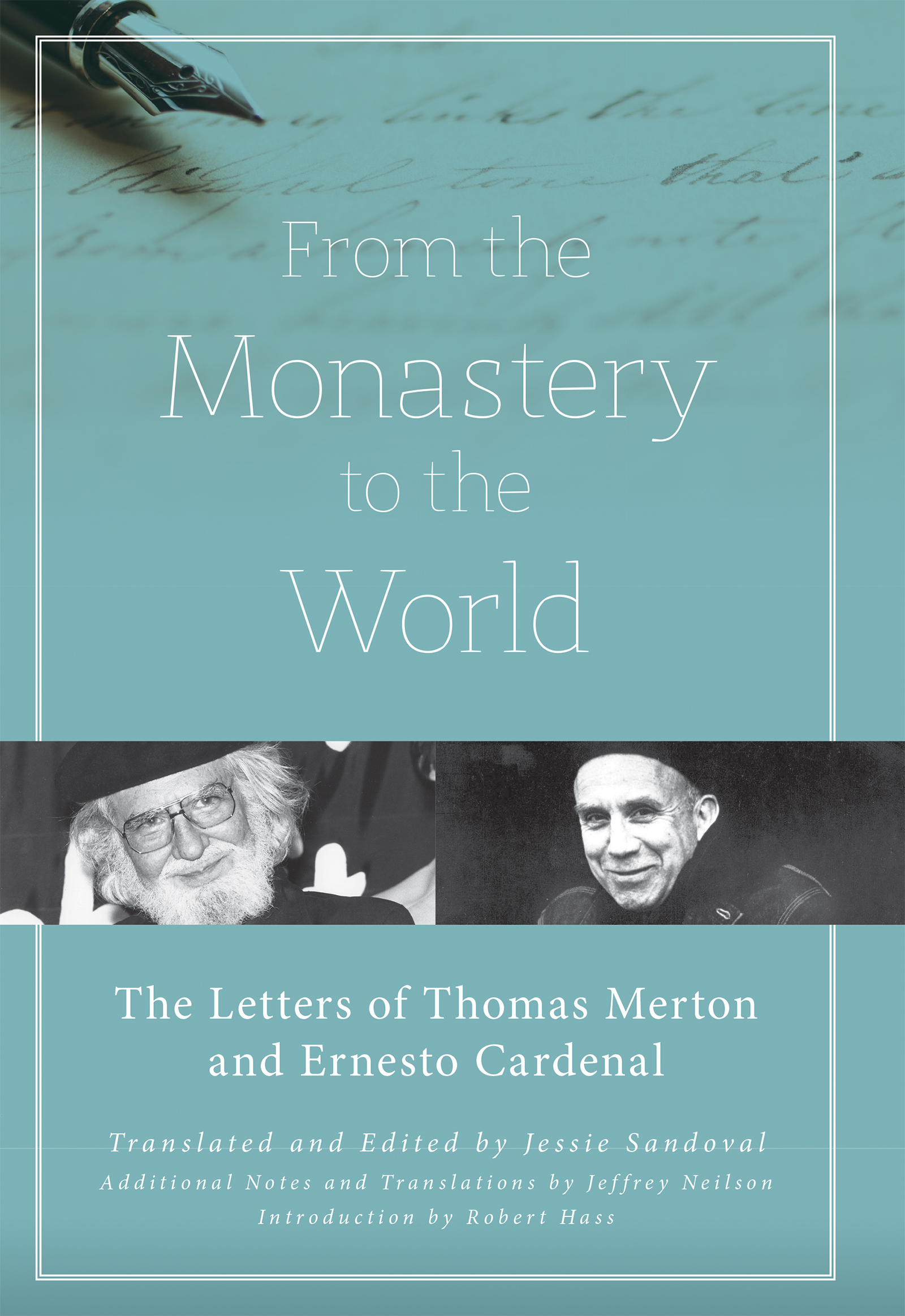

Its hard to know where to begin to tell the story of the letters that passed between these two poets more than fifty years ago. Thomas Merton was forty-two years old, eight years a priest and fifteen years a contemplative under a rule of silence at the Cistercian Abbey of Gethsemani in rural Kentucky when the young Nicaraguan poet arrived there to become a novice monk in the fall of 1957.

Cardenal would stay in the monastery for two years. He left in 1959 and moved to a seminary in Cuernavaca, Mexico, and from there to another in Colombia to prepare for the priesthood with the intention of returning to Nicaragua to create a spiritual community and arts center among the peasants and indigenous peoples of his country.

This mission was a dream Cardenal and Merton came to in their time together, and one that was going to have consequences well into this century. Cardenal did found his mission, among peasants and fisherman on an archipelago in a vast lake in the center of his country. Cardenal encouraged his parishioners to read from the New Testament, to read passages aloud to those among themthe majoritywho could not read, and to offer their own interpretations. He recorded these sessions and published the results in four volumes during the years of the emergence of an active liberation theology in Latin America. In 1977 the Nicaraguan dictator, Anastasio Debayle Somoza, sent his army to the island and burned the church and meeting halls at Solentiname to the ground. In 1979 Cardenal joined the Sandinista Revolution that overthrew the fifty-year Somoza family dictatorship, and he became minister of culture to the new government. In 1983 the Polish pope John Paul visited Nicaragua and publicly rebuked Cardenal, a priest, for holding a government position. In the next year he defrocked Cardenal, stripping him of his priesthood. It was a turbulent time. Five years later, six Jesuit professors involved with liberation theology were murdered in their home by the right-wing death squads of a government in El Salvador supported by the United States. In 1994 Cardenal resigned from the government to protest an authoritarian turn in the ruling party. Twenty years later, in 2013 the Argentine bishop Jorge Mario Bergoglio became Pope Francis, the first Latin American to hold the papacy. In 2014 Pope Francis reinstated the priesthood of Father Cardenal.

This book is a record of the correspondence between the two men from the time of Cardenals departure in 1959 until the time of Mertons untimely death in a hotel near Bangkok, Thailand, in 1968. He was attending an interfaith conference on monastic life with Buddhist and Hindu monks and scholars. Always interested in Hindu and Islamic and Zen Buddhist spirituality, he had been enormously excited to travel to Asia. When he diedelectrocuted by the faulty wiring in a fan in his hotel roomhe was the most revered, most widely read writer about spirituality in the English language.

The Abbey at Gethsemaniwhere Merton and Cardenal metwas a communal farm founded by a group of French Cistercian monks in the middle of the nineteenth century about an hour south of Louisville, an hour and a half from the countryside of that other Kentucky poet, essayist, and farmer, Wendell Berry. The year was 1848, a time of political and social revolt in France, so that the founding of a monastery in the new world mimicked in some way the origins of monasticism. The Cistercian order had its beginnings in a movement that swept Europe in the years of the disintegration of the Roman empire, when some groups of Christian men or women withdrew into communities where they shared work, renounced worldly attachments, and devoted themselves to their spiritual lives. The Cisterciansalso called Cistercians of the Strict Observancealso called Trappists for their abbey named La Grande Trappe, in the French countrysidefollowed the most demanding of the rules set down for monastic life. Trappist monks took three vows: a Vow of Stability, which meant that they were committing themselves to living in the monastery they were entering for the rest of their lives; a Vow of Obedience, which meant that they would do as they were told by their religious superiors; and a Vow of Conversion of Manners, as it was called, which committed them to a life of celibacy, fasting, manual labor, separation from the world, and silence.

What separation from the world meant seems to have changed over time with regard to issues like communication with family and friends in the outside world, which was rationed, but it was certainly a vow of poverty and simplicity; monks entering upon the life were required to make a will disposing of their earthly goods. Fasting at Gethsemani meant a simple vegetarian diet and occasional periods of fasting in accordance with the Churchs liturgical calendar. There were three exceptions to the rule of silence: one could do the speaking necessary to organize work; one could speak during organized group discussions; and one could speak when discussing ones spiritual life in formal meetings with ones confessor or spiritual director. The idea was to live simply, keep quiet, work hard, and disappear into ones relationship with God. Some American version of this medieval regimen was the one that these two distinctly twentieth-century poets had entered, Thomas Merton in the winter of 1941 and Cardenal in the fall of 1957.

Next page