Copyright 2015 Donald Grayston. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical publications or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Write: Permissions, Wipf and Stock Publishers, W. th Ave., Suite , Eugene, OR 97401 .

W. th Ave., Suite

Grayston, Donald.

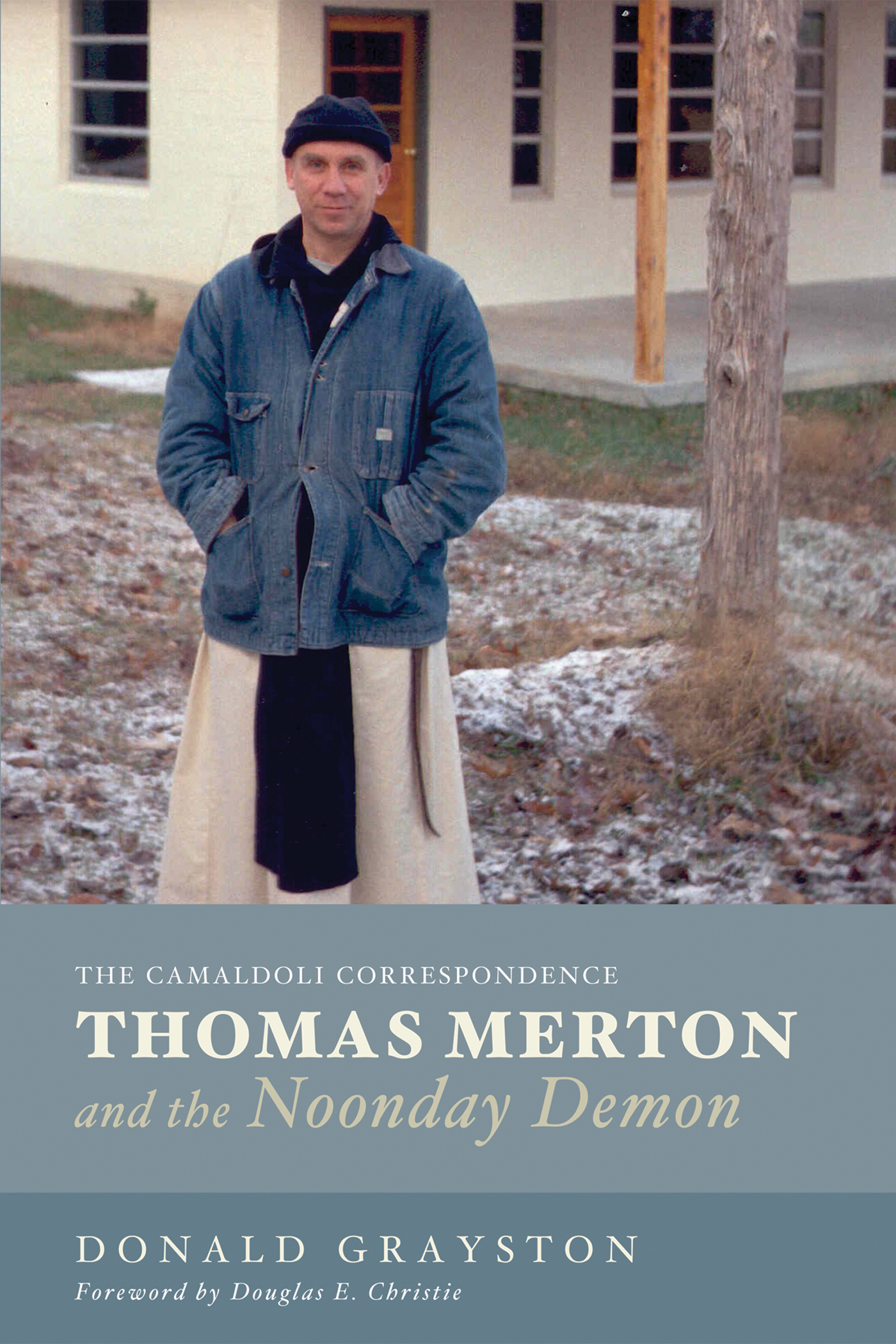

Thomas Merton and the noonday demon : the Camaldoli correspondence / Donald Grayston ; foreword by Douglas E. Christie.

xxii + p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index.

. Merton, Thomas, 19151968 .. Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani (Trappist, Ky.). Eremo di Camaldoli. Monastero di Camaldoli. 5. A cedia.. Monastic and religious life. I. Christie, Douglas E. II. Title.

Manufactured in the U.S.A.

Permissions

The following permissions are gratefully acknowledged.

Unpublished letters and notes of Thomas Merton are used with permission of The Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University. Previously unpublished letters by Thomas Merton, Copyright 2015 by The Trustees of the Merton Legacy Trust.

Unpublished letters of Abbot James Fox are used with permission of Abbot Elias Dietz on behalf of the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani. Extracts from The Sign of Jonas, p. [ words] and [ words, for a total of words]. Used with permission of Abbot Elias Dietz on behalf of the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani.

Unpublished letters of Dom Anselmo Giabbani and the anonymous description of the Italian Camaldolese houses are used with permission of Dom Alessandro Barban, prior general of Camaldoli.

An unpublished letter of Dom Pablo Maria, O.Cart. (Thomas Verner Moore) is used with permission of the Carthusian Foundation, Arlington, Vermont.

Unpublished letters of Archbishop Giovanni Battista Montini (Pope Paul VI) are used with permission of the Archivio Storico Diocesano di Milano.

Letter To Dom Gabriel Sortais October , 1955 from The School of Charity: Letters of Thomas Merton on Religious Renewal and Spiritual Direction , by Thomas Merton, edited by Brother Patrick Hart. Copyright by the Merton Legacy Trust. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

Excerpts from Survival or Prophecy? The Letters of Thomas Merton and Jean Leclercq , edited by Brother Patrick Hart. Letters by Thomas Merton copyright 2002 by the Abbey of Gethsemani. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

Excerpts from Witness to Freedom , by Thomas Merton, edited by William H. Shannon. Copyright 1994 by the Merton Legacy Trust. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

Quotes from pp. , , , , [ words] from Entering the Silence: Becoming a Monk and Writer , vol. of The Journals of Thomas Merton , edited by Jonathan Montaldo. Copyright 1995 by The Merton Legacy Trust. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Seventeen quotes [pp. : words] from A Search for Solitude: Pursuing the Monks True Life , vol. of The Journals of Thomas Merton , edited by Lawrence S. Cunningham. Copyright 1996 by The Merton Legacy Trust. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Quotes from pp. , ,, , [ words] from Turning Toward the World: The Pivotal Years , vol. of The Journals of Thomas Merton , edited by Victor A. Kramer. Copyright 1996 by The Merton Legacy Trust. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Quotes from pp. , , , , [ words] from Dancing in the Water of Life: Seeking Peace in the Hermitage , vol. of The Journals of Thomas Merton , edited by Robert E. Daggy. Copyright by The Merton Legacy Trust. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

The hymn Yield Not to Temptation, quoted in chapter , is in the public domain, and is reprinted from The Book of Common Praise , copyright 1938 by the Anglican Church of Canada, and published by The Anglican Book Centre.

Letter , from Cardinal Arcadio Larraona, CMF, to Thomas Merton, is reprinted with the permission of Father Jose-Flix Valderrbano, CMF, Secretary General of the Claretian Congregation.

Foreword

A long-neglected cache of letters is unearthed in an ancient Italian monastery. They are copied and with the consent of the monastery made available to us by an intrepid soul who understands their value. He turns them into a book that promises to offer new insight into a renowned spiritual writerthe very book you have before you.

It is a strange tale, and an intriguing one. And if it sounds like a story more suited to a tabloid newspaper than the pages of the book, you would not be far wrong. It has all the elements of a potboiler: some of the letters were written secretly, sometimes in code. They involve a not entirely transparent effort to manipulate and possibly deceive certain persons in order to achieve a particular end. It feels like a plot, or to use language common in old Jimmy Cagney movies, a caper. And in a sense it is. Which is part of the charm of the letters and the story they tell. Still, to characterize the story in this way hardly does justice to its complexity and depth. Neither does it adequately express why these letters and the story they tell matter, or might matter to us. Which, I believe, they do.

The story Donald Grayston tells in this book does indeed arise from his discovery of said cache of letters. The author? Thomas Merton, who was at the time of their writing in the mid- 1950 s living as a Trappist monk (and well-known spiritual writer) at the Abbey of Gethsemani, in Kentucky. He had come to a kind of impasse in his monastic vocation and thought it would be best for him to leave Gethsemani, ideally for a monastic community where solitude was taken more seriously. Thus his correspondence with the superior of the Monastery of Camaldoli in Italy. And yes, it had to be conducted in secret, with code words used for delicate matters having to do with Mertons possible transfer(say the roses are in bloom if the way looks clear, Merton says to the Italian superior)lest his abbot at Gethsemani discover what he was planning and put an end to Mertons hopes for a transfer.

Much of this is humorous, both in the intended and unintended senses. It is indeed hard not to smile (or wince) when reading parts of this correspondence. The intrigue, the evasions, the secrets. The only thing missing is invisible ink. Still, for Merton, the stakes were high. He did, after all, feel as though he had reached the end of something in himself and was no longer certain he would be able to continue his monastic vocation at Gethsemani. He was pinning all his hopes on a transfer to Camaldoli. Perhaps he was justified in being cautious, secretive, even devious in the way he conducted this correspondence. He was in turmoil and he was seeking a way forward, a way out.

All of this matters to our understanding of the correspondence. But it is not all that matters. That, it seems to me, is the insight these letters provide about a moment in Thomas Mertons life that would determine so much of what was to follow. A moment of truth, as we sometimes say. For the letters reveal, not always in a way that places Merton in a favorable light, what it feels like to grapple with the kind of fear, anxiety, and uncertainty that can sometimes undo a person. A moment of crisis in which it no longer feels possible to imagine a future. When life has lost its savor. When the struggle you are engaged in to understand and come to terms with yourself is no casual matter but will determine how you will live from this point forward. It is in this sense that the letters matter, or might matternot only to our understanding of the life and writings of Thomas Merton but also, potentially, to our understanding of ourselves.