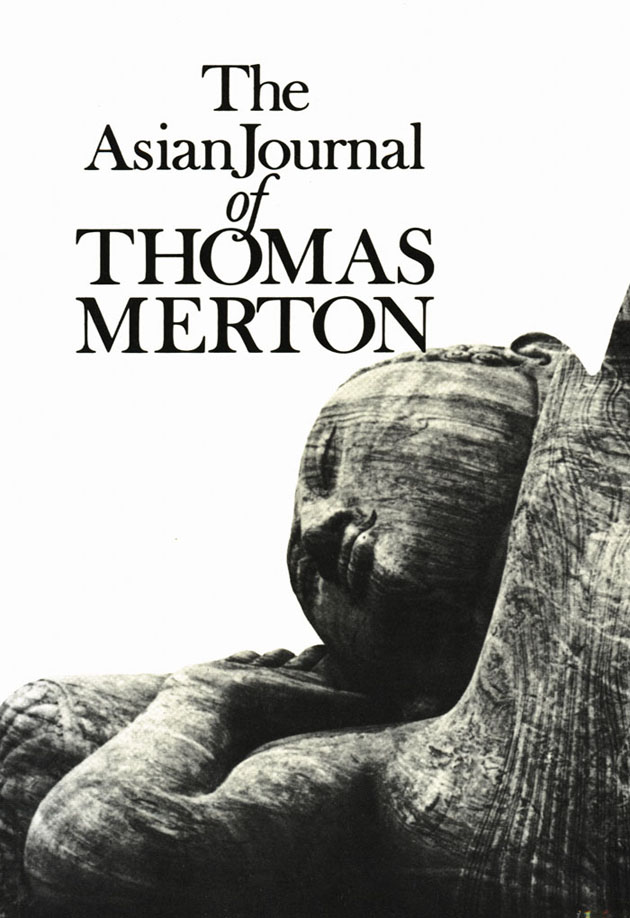

PREFACE

Readers of Thomas Merton know that his openness to mans spiritual horizons came from a rootedness of faith; and inner security led him to explore, experience, and interpret the affinities and differences between religions in the light of his own religion. That light was Christianity. For him it was the supreme historical fact and the perfect revelation, but affirmations in many lands and traditions and, as St. Paul indicated, the witnesses, were there; the witnessing continues. Merton sought fullness of mans inheritance; this inclusive view made it impossible for him to deny any authentic scripture or any man of faith. Indeed, he discovered new aspects of truth in Hinduism, in the Madhyamika system, which stood halfway between Hinduism and Buddhism, in Zen, and in Sufi mysticism. His lifelong search for meditative silence and prayer was found not only in his monastic experience but also in his late Tibetan inspiration. His major devotional interests converged in what he called constantia where all notes in their perfect distinctness, are yet blended in one. Believing in ecumenicity, he went further and explored new avenues of interfaith understanding, encouraged by the open spirit of Vatican II.

Not only in religion and in religious philosophy but in art, creative writing, music, and international relationsparticularly in a possible world renunciation of violencehe knew the challenge of reality. Intellectual illumination and phases of doubt enhanced the religious process; therefore, in a sense, he never withdrew from the world. Sometimes a bright idea would capture his imagination, and he might tend to overvalue it in the context of conformity. Perhaps it might even be said that he had carried over an experimental attitude from his secular days and made concessions to a social culture to which, he thought on entering the monastery, he no longer belonged. But he adjusted this impulsive quality to his acceptance of the rituals and basic dogmas of his life as a monk and a priest. The search for diversities is never free from an element of risk. But his long years of arduous discipline and his insights produced a deep religious maturity, and his encounters with other religions and religious cultures never found him unresponsive, nor irresponsible in regard to his own commitment. The monk of Gethsemani did not desert his own indwelling heights when he climbed to meet the Dalai Lama in the Himalayan mountains. In a way his disciple-ship of Jesus grew as he gained the perspective of divine faith; in Asia, he felt the need to return to his monastery in Kentucky with newly affirmed experiences.

Thomas Merton never quite accepted a fixed medieval line between the sacred and the profane. In this he was a modern Christian thinker and believer who had to redefine, or leave undefined, the subtle balance of the religious life.

The richness of this book, with its hurried jottings, referrals, notes on conversations, shifts in scenic travels along with profound insightsinterspersed with light lyrics and humorposed many problems. The editorial board had to consult Mertons friends and acquaintances in far-flung Asian and Western continents; even then some doubts remained as to the exact text and context. The authors erudition and phenomenal memory, as well as his capacity to absorb and reciprocate ideas, sometimes turned his pages into lists of terms and even cryptic puzzles (where the right order could not be traced)but the editorial collaboration with many authors and correspondents, as the reader will find, led to very satisfactory results. The book is richly cohesive. Without changing the original, as Merton would surely have done in revision, every sentence has been scrutinized and notes (and appendixes and glossary) provided. Where the indigenous words were spelt differently, the variations have been preserved; sometimes the mutational changes of wordsfrom Sanskrit to Pali, for instancehad to be kept as they were quoted or interpreted by the author. No uniformity brought about by diacritical marks has been imposed, the words appear as they were originally written down in the journal, and also as they are still mostly known to the general public. This meant some sacrifice of academic levels but also an avoidance of stiffness which would have turned the book into a treatise. The improvised nature of the book, where fancy as well as an artists composition may fling a Tamil word, a French quote, and a Tibetan mandala together, where excerpts from the local paper and a metaphysical discourse are juxtaposed, seemed to go well with the varied and incidental spelling and diction. This does not affect the high seriousness of the book, while it provides color to the rocklike structure and the skies of an unusual pilgrimage.

These pages reveal the character and circumstances of a rare and beloved person. It is a book which seemingly ends in tragedy: but the tragic element, which is a part of life, is transcended by his vibrant humanity.

New Paltz, N.Y.

August 1971 | A MIYA C HAKRAVARTY

Consulting Editor |

EDITORS NOTES

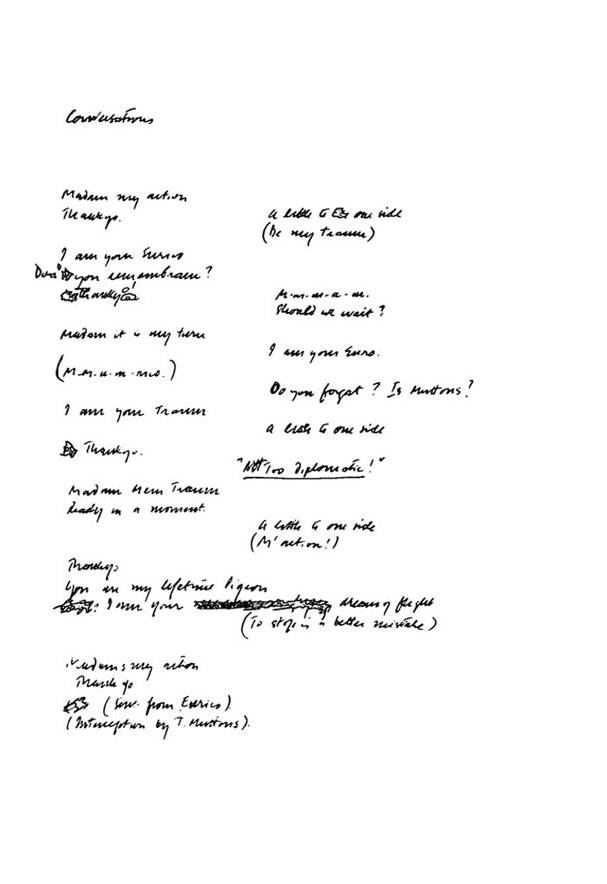

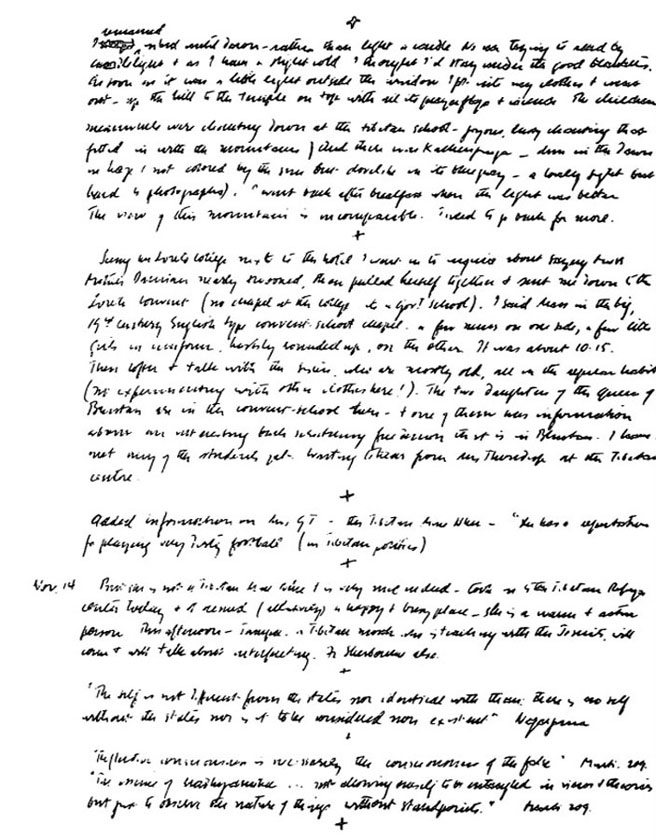

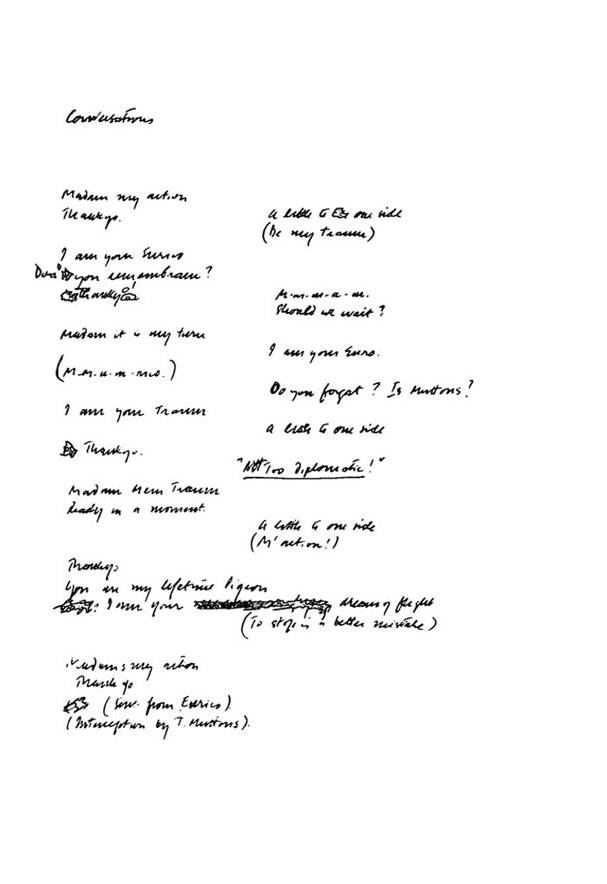

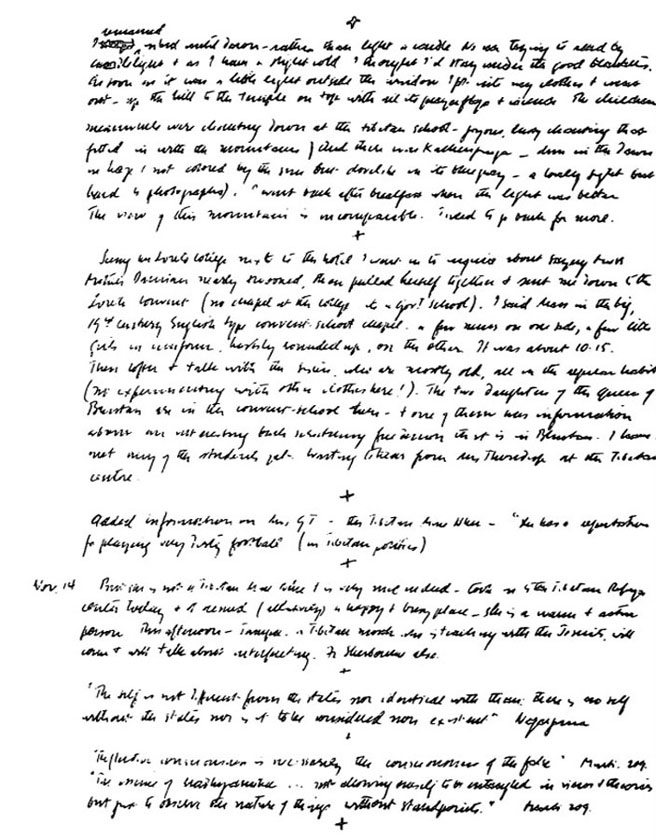

The preparation of a publishable text of Thomas MertonsAsian Journal was a complicated process. A glance at one of the facsimilereproductions of typical pages from the holograph diaries (see pages xii-xiii) willshow how rapidly Merton wrote them, often making it difficult, even for those of uswho had known his handwriting for many years, to decipher certain words,particularly Asian names or terms with which we were not familiar. A second problemwas that Merton spelled many of these Asian words phonetically, that is,by as close a guess as he could make to how they had sounded in the daysconversations; some of these words were easy to check in reference works, but forothers we were obliged to locate and correspond with some of the many friends whomhe had made in his travels. The prompt help which these persons gave us bore witnessto the devotion and esteem which even a brief encounter with Merton couldinspire.

Related to this difficulty with spellings was the whole problem oftransliteration into English from Pali, Sanskrit, Tibetan, and other Asianlanguages. Few authorities agree on systems for transliteration, this beingespecially true of Tibetan. Modern scholarship, to be sure, has evolved a complexsystem of diacritical marks for the English rendering of most of these languages,but since Merton himself almost never used the diacriticals in the Journal,we decided against an attempt to supply them. Nor did we try tomake his spellings consistent in cases where he had used the Pali spelling of a termat one point and the Sanskrit spelling of its cognate version in another, or to makehis spellings, as long as there was authority for them, agree with those insource books from which he quoted. In what is intended as a spirit of ecumenism, wedid not italicize foreign-language words except in quotations from other books. Wecapitalized only the names of religions, their major sects, and divinities.

Facing pages from Mertons Asian diary, entries dated November 1314, 1968

So much for the minor problems of orthography. A far largerdecision had to be made in the matter of editing for style. If, as was true for manyof his earlier books, Merton had composed directly on the typewriter, this issuewould have been minimized; practically no style changes had ever been required onthe typewritten texts of other books he had sent to New Directions for publication.But in the haste of composing in hand, and often late at night or in odd momentssnatched from a busy schedule of meetings and sightseeing, he wrote the