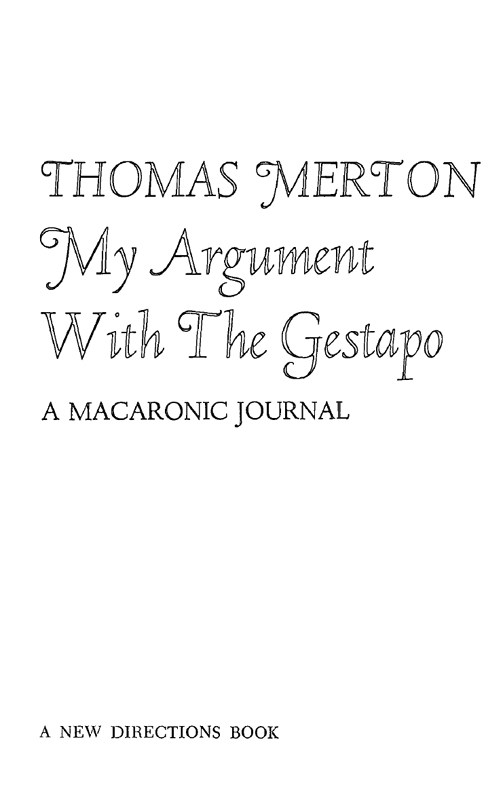

My Argument With The Gestapo

A MACARONIC J OURNAL

I sacrifice this Iland unto thee,

And all whom I lovd there, and who lovd mee;

When I have put our seas twixt them and mee

Put thou thy sea betwixt my sinnes and thee.

Donne

By Thomas Merton

THE ASIAN JOURNAL

COLLECTED POEMS

EIGHTEEN POEMS

GANDHI ON NON-VIOLENCE

THE GEOGRAPHY OF LOGRAIRE

THE LITERARY ESSAYS

MY ARGUMENT WITH THE GESTAPO

NEW SEEDS OF CONTEMPLATION

RAIDS ON THE UNSPEAKABLE

SEEDS OF CONTEMPLATION

SELECTED POEMS

THE WAY OF CHUANG TZU

THE WISDOM OF THE DESERT

THOMAS MERTON IN ALASKA

ZEN AND THE BIRDS OF APPETITE

About Thomas Merton

WORDS AND SILENCE: ON THE POETRY OF THOMAS MERTON

by Sister Thrse Lentfoehr

Published by

New Directions

Copyright 1969 by the Abbey of Gethsemani, Inc.

Copyright 1968 by Thomas Merton

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 6920082

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or website review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Ex parte ordinis

Imprimi potest:

Fr. Vincentius Hermans

Procurator General, Rome

10 October 1968

Originally published clothbound in 1969 by Doubleday & Company, Inc.

First published as New Directions Paperbook 403

(ISBN: 081120586x) in 1975

ISBN: 978-0-8112-2393-5 (e-book)

New Directions Books are published for James Laughlin

by New Directions Publishing Corporation,

80 Eighth Avenue, New York 10011

AUTHORS PREFACE

One Sunday morning in the spring of 1932 I was hiking through the Rhine Valley. With a pack on my back I was wandering down a quiet country road among flowering apple orchards, near Koblenz. Suddenly a car appeared and came down the road very fast. It was jammed with people. Almost before I had taken full notice of it, I realized it was coming straight at me and instinctively jumped into the ditch. The car passed in a cloud of leaflets and from the ditch I glimpsed its occupants, six or seven youths screaming and shaking their fists. They were Nazis, and it was election day. I was being invited to vote for Hitler, who was not yet in power. These were future officers in the SS. They vanished quickly. The road was once again perfectly silent and peaceful. But it was not the same road as before. It was now a road on which seven men had expressed their readiness to destroy me.

That was about the closest I ever really came to direct contact with Nazi violence in its overt form. What this novel is about is really something different. It is about the crisis of civilization in general, and the Germany it deals with is still largely that of Bismarck and the Kaiser. It is the Germany that accepted Nazism. Nazism itself was beyond me!

The book was written in the summer of 1941, when I was teaching English at St. Bonaventure University. I wanted to enter the Trappists but had not yet managed to make up my mind about doing so. This novel is a kind of sardonic meditation on the world in which I then found myself: an attempt to define its predicament and my own place in it. That definition was necessarily personal. I do not claim to have gained full access to the whole myth of Europe and the West, only to my own myth. But as a child of two wars, my myth had to include that of Europe and of its falling apart: not to mention America with its own built-in absurdities.

Obviously this fantasy cannot be considered an adequate statement about Nazism and the war. The death camps were not yet in operation. America was not yet involved. The things that were to come could, at best, be guessed at: but even the wildest and most apocalyptic guesses would never have imagined the inhumanities that soon became not only possible but real. In the face of such things, this book could never have been written so lightly. Therefore the reader must remember that it was dreamed in 1941, and that its tone of divertissement marks it as a document of a past era.

What remains actual about it of course is this: the awareness that, though one may or may not escape from the Nazis, there is no evading the universal human crisis of which they were but one partial symptom.

Abbey of GethsemaniJanuary 1968

A NOTE ON THE AUTHOR AND THIS BOOK

On December 10, 1968, Thomas Merton died at the age of fifty-three in Bangkok, Thailand, where he had gone to attend a meeting of Abbots of all the Catholic Monastic Orders in Asia. He was born on January 31, 1915, in Prades, France, the older of two boys. His parents were both artists, his father a New Zealander and his mother an American. In 1916 the family moved to the United States, and when Mrs. Merton died five years later, the two boys lived with her parents for some years. In 1925 Merton returned to France with his father and attended the Lyce Ingres at Montauban. When he was fourteen they went to live in England and Merton entered Oakham School, in Rutland. Two years later (1931) his father died in London from a brain tumor. It was his wish that his son should complete his education in England, so Merton remained at Oakham, spending his vacations with family friends or traveling in Europe. In 1933 he won a scholarship to Clare College, Cambridge, but after one year he returned to his maternal grandparents home in Douglaston, Long Island, and entered Columbia University in 1935, receiving his B.A. in 1938 and his M.A. in 1939.

On December 10, 1941, he entered the Older of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (Trappists), a silent, contemplative order, at Gethsemane, Kentucky. He expected to give up entirely his early ambition to be a writer, but after some years of rigorous training in the Trappist life and studying for the priesthood (he was ordained in 1949) he was encouraged by his abbot to write again. His first published book was Thirty Poems (New Directions, 1944). In 1948 his first prose work, The Seven Storey Mountain, was brought out and became an almost immediate international best-seller. It was followed by some thirty or more books of prose, poetry, and translation. For many years Merton was considered to be one of the leading writers in the world on the spiritual life, but recently he had more and more turned his attention to matters that had always deeply concerned himpeace, civil rights, ecumenismand to a subject that had interested him since his undergraduate days, the religions of the Far East.

In thinking of Thomas Merton as a monk (since 1965 a hermit living alone in the woods near the abbey) it is sometimes hard for people to understand his passionate interest in the problems of our time. The fact is the monks are no longer so sheltered from the world that they do not know what is happening outside their own walls, and Merton carried on a vast correspondence, read prolifically, and received visitors from all over the world and from all walks of life. It was not really possible for him to shut out the world. Even in the peaceful wooded hills of Kentucky he could hear the distant boom of the guns at Fort Knox and write: I have seen the SAC plane, with the bomb in it, fly low over me and I have looked up out of the woods directly at the closed bay of the metal bird with a scientific egg in its breast! More and more, it seems to me, the concerns of the last years of his life were the same concerns that occupied him in 1940, when I first made the acquaintance of a blond young man who had a novel he wanted published.