Contents

Guide

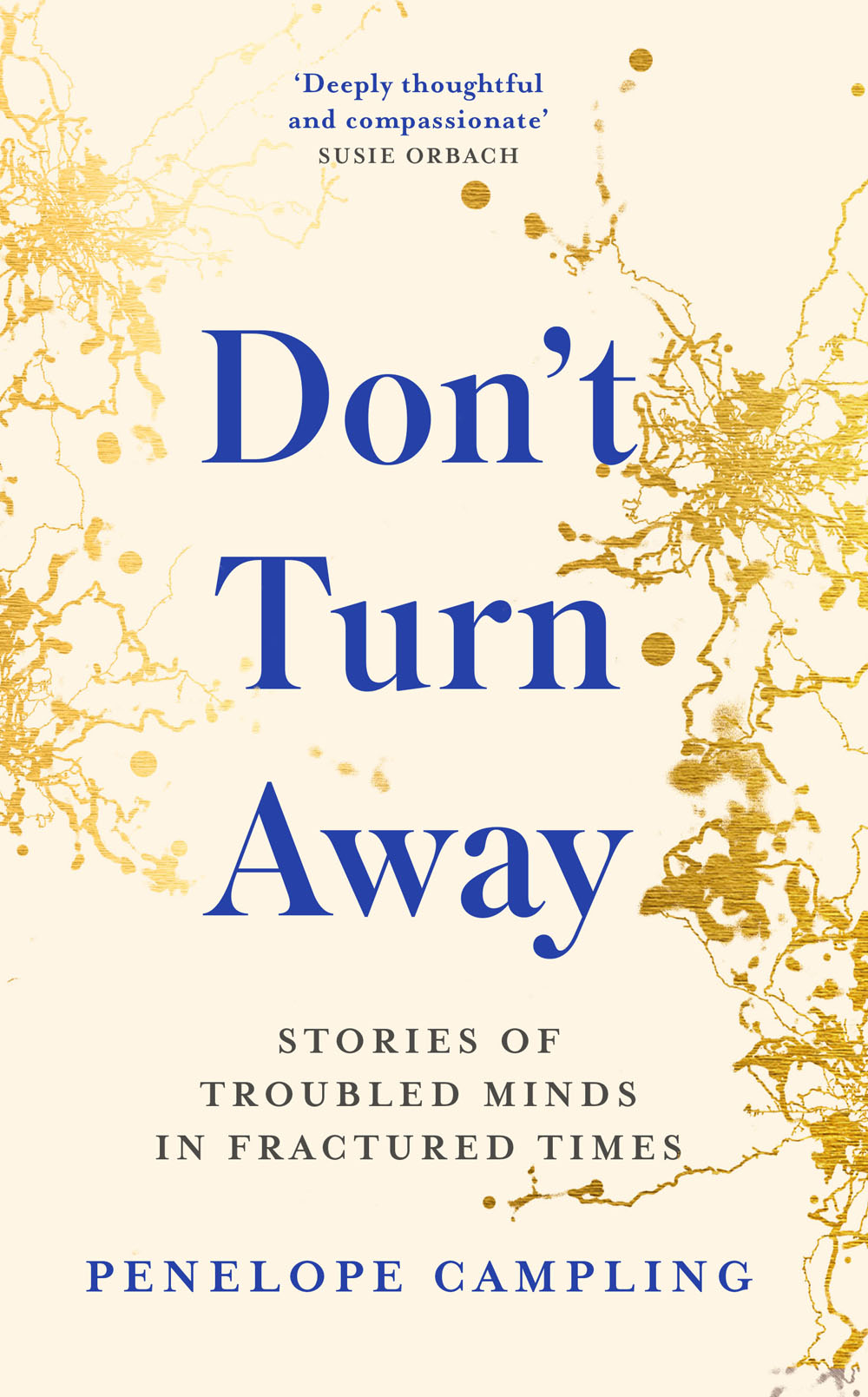

This book is dedicated to those struggling with severe mental health problems who find themselves unable to access the support they need and deserve; and to those mental health workers who continue to give their all in very difficult circumstances.

And in memory of Dr Steve Pearce, who died too young after a long illness, one of the kindest and the best.

AUTHORS NOTE

This book and the stories within it are based on my clinical experience. Some people have generously agreed to appear in these pages, but the book covers many years and it has not been possible to trace everyone. I have therefore changed details of people and incidents, trying to remain true to their essence, but mindful of the need to protect confidentiality and privacy.

The stories in this book touch on some difficult and distressing topics. If you are affected by any of the themes covered in these pages, you can call Samaritans on 08457 909090 or visit the Samaritans website to find details of the nearest branch.

Many mental health trusts now operate a central access line for acute problems. You can find the number by visiting your local trusts website.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I am worried about Prabha. She is a happily married, successful doctor with no history of mental health problems and yet shes increasingly preoccupied with the thought of suicide. For many months she has been working in an intensive care unit with Covid-19 patients. She is deeply exhausted and finds herself wishing it would all stop. Images of ending her life keep intruding into her mind.

That must be frightening. Can you tell me a bit more about what youve been imagining? I ask gently.

Just stuff, she says in a tiny voice, after a long delay and avoiding my eyes. She looks painfully embarrassed, like a child caught stealing. She shakes her head rapidly from side to side as if shes trying to free herself of the pictures insistently pushing through to the surface. She is ashamed of these thoughts; they feel alien and she assures me she would never act on them. Over and over again, she tells me how well she functions in ordinary times. Like many clinicians working in ICU, Prabha has a deeply set belief in her own resilience. Asking for support is not something that comes easily but she is frightened at how little control she has over her mind at the present time. Im a bit frightened too. The incidence of suicide is higher in doctors than in the general population, and anaesthetists like Prabha are thought to be particularly at risk we both know that with so many drugs at hand she has the means of killing herself at her fingertips.

Later that day, Tom, another senior ICU doctor, sits head in hands and tells me he feels crushed. He used to love his job but now dreads coming to work. He knows hes not functioning well and might make a mistake. But despite being more exhausted than he ever thought possible, he also knows that the staffing shortages have become so acute that standards are dropping to a dangerous level and he cant bear the thought of taking time off and leaving his colleagues with even more pressure. He is having fleeting self-destructive thoughts while driving, enticed by the idea of oblivion rather than actually killing himself. Somehow, I need to help Tom rediscover his sense of agency, but his burdensome circumstances weigh heavy and it would be easy to be infected by his sense of helplessness.

Working with ICU staff during the pandemic brings home the precariousness of the healthcare systems that are there supposedly to help us in our hour of need. Having endured my own experience of trying to hold a mental health team together through bad times, there is something about watching another service under severe stress once removed as it were, in relative comfort as therapist and witness that makes me want to shout about it and make people listen. It makes me think about the fragility of progress and how easy it is for things to go into reverse.

I started my career as a psychiatrist nearly forty years ago at the Towers, one of two Victorian asylums in Leicester. It was a profoundly flawed institution where I encountered patients who had been locked away and forgotten for years institutionalised, infantilised, their individuality eroded. Some of them had originally been admitted decades earlier for no better reason than theyd had an illegitimate baby. And yet I began that first job full of optimism. We all knew that change was under way: plans to close the Towers were already in place, and the generation before us had taken huge steps towards humane care, reforming the Mental Health Act and breaking down the barriers between the asylums and the community. We believed in progress. It was an era filled with hope.

Just six months later, I moved on to a brand new mental health unit attached to the General Hospital. It was a hugely significant change, one that reflected the reforms taking place throughout the country, indeed throughout most of the richer countries in the world. The building itself seemed to embody a new and hopeful chapter in the history of psychiatry. At the time it felt as if I was part of a great leap forward, playing a small part on the right side of history, my future career glittering in my imagination with grateful patients, exciting discoveries, and a palpable sense of progress.

And indeed some things did improve. We now understand a lot more about the human mind and have a growing evidence base informing us how best to help people who are struggling. There has also been a sea change in attitudes to mental health more generally. People are more open about their feelings, and mental health problems are no longer the taboo they were a generation or two ago. Celebrities even royalty talk publicly about their battles with mental illness. Mental well-being and mindfulness have become part of everyday language and therapy is increasingly seen in some sections of society, at least as a normal, healthy thing to do. Public health campaigns reassure us that there is no shame in sharing feelings of despair and thoughts of suicide and remind us that mental health problems will affect as many as one in four of us at some point in our lives.

But despite all of this, mental health services have not thrived in recent years. Morale is desperately low on the front line. People with serious mental illness are likely to die on average fifteen to twenty-five years earlier than those without SMI, largely from preventable diseases such as heart disease and diabetes. Report after report has confirmed what every mental health worker knows: that the service is in a terrible state and that the shocking chasm between what is needed and what we are actually resourced to provide is getting larger, leaving an increasing number of vulnerable people and their families in dark and desperate states of mind. The theme tunes seem horribly familiar as the potential for depriving, brutalising and dehumanising mental health patients re-emerges in different settings. To my great sadness, we seem to be moving backwards: the progress made during my early career steadily eroding.