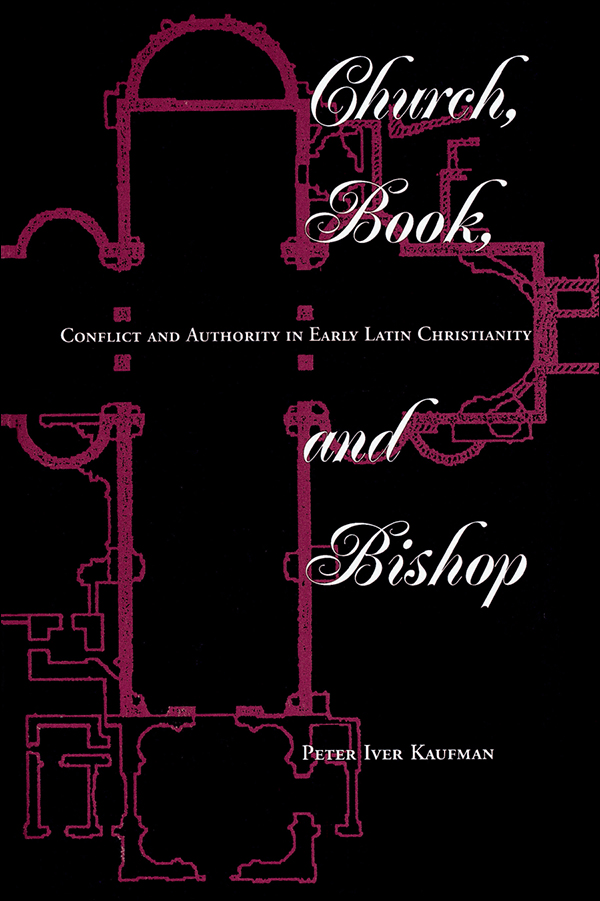

Church, Book, and Bishop

EXPLORATIONS

Contemporary Perspectives on Religion

Lynn Davidman, Gillian Lindt, Charles H. Long, John P. Reeder Jr., Ninian Smart, John F. Wilson and Robert Wuthnow, Advisory Board

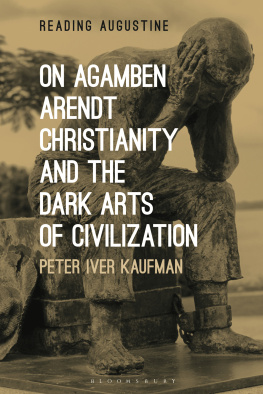

Church Book, and Bishop: Conflict and Authority in Early Latin Christianity Peter Iver Kaufman

Religion and Politics in America: Faith, Culture, and Strategic Choices Robert Booth Fowler and Allen D. Hertzke

Birth of a Worldview: Early Christianity in Its Jewish and Pagan Context Robert Doran

FORTHCOMING

New Religions as Global Cultures Karla Poewe and Irving Hexham

Images of Jesus L. Michael White

Religious Ethos and the Rise of the Latino Movement Anthony Stevens-Arroyo and Ana Mara Diaz-Stevens

Transformations of the Confucian Way John Berthrong

Ancient Israelite Religion Saul Olyan

Church, Book, and Bishop

CONFLICT AND AUTHORITY IN EARLY LATIN CHRISTIANITY

Peter Iver Kaufman

University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

Explorations: Contemporary Perspectives on Religion

First published 1996 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon 0X14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1996 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 13: 978-0-8133-1817-2 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-8133-1816-5 (hbk)

Contents

It has been a strange two years writing about conflict and writing rather favorably about the management strategies of the early churches executives while pressing the executives at my university for substantial change. I owe much to the dozens of colleagues who participated in that latter initiative, educators who insist that values they impart in their classroomsinquiry, honesty, and excellencebe reflected in the management of their campus. I dedicate this book to my two closest collaborators and good friends, Melissa Bullard and Terry Evens, and to Professor Robin Scroggs of Union Theological Seminary in New York, who awakened my interests in the earliest Christians.

Trent Foley of Davidson College threw caution to the wind and assigned an early draft of Church, Book, and Bishop to the students in his class on Christian antiquity in 1994. Their comments and criticisms enabled me to improve the text, as did Trents interest and suggestions. Bart Ehrman, Maureen Tilley, Carolyn ood, John Headley, and Kim Haines-Eitzen gave invaluable advice. At Westview, Spencer Carrs encouragement, patience, and counsel were all an author could wish for. I am grateful to them all; defects that remain are my own doing.

Peter Iver Kaufman

Cranbrook in Kent was a rather sleepy small town in 1583, slightly more than twenty miles southwest of Canterbury. Dudley Fenner was twenty-five when he arrived there that year, having just returned to England from Antwerp. He had been ordained a priest on the Continent yet was pleased to have been assigned a parish close to his birthplace. Later in the year, Bishop John Whitgift of Worcester came to Canterbury to be consecrated as archbishop, the principal administrator of the reformed English church. These two men were a mere twenty miles apart, but they did not see the same prospects when they looked back at Christian antiquity. Whitgift found that the apostles had been the churchs first bishops. He and his friends inferred God had authorized the concentration of power in the church in the hands of a few able, distinguished administrators. Fenner protested that the earliest churches had been governed differently, more democratically. Popular consent had been required, elders consulted, councils called. Not one to pull his punches, Fenner pronounced that Whitgift and other apologists for the established church order in England, wanting to retain their salaries and privileges, faleslie father[ed] upon the apostles a false and bastard distinction of ministries.

Origins seem sacred in many, if not most, religions. What happens at the start and the meanings that originators give to what happens acquire tremendous authority. Appeals to the very beginnings of this or that practice argue for its continuation. Memories of the first shoots of an idea argue for its repetition and ramification. For nearly two millennia, Christians have been ascribing normative status to Christian antiquity, to all or the earliest part of the religions first six centuries. Looking back is hard, Christians have learned; what was thought, done, and meant usually defies precise determination. And looking back is competitive, as Whitgift and Fenner discovered; those who search for origins must reinvent them while trying to reappropriate them.

My interests were like those of Fenner and Whitgift, though I was not looking to reappropriate, to find patterns in what was for what is or ought to be. Even so, disclaimers of this sort do not diminish all difficulties. Although historians may not have to contend with resistances to reappropriation, they must nevertheless narratively reinvent a past that has left only modest stocks of evidence, and they must always compete with rival explanations. My interests in the early churchs management strategies further complicated this enterprise because management is a monster category. It compasses liturgical and teaching responsibilities as well as political initiatives ranging from recrimination to reconciliation. To tame the monster, I tried to put many rituals and doctrines in contexts dominated by more overtly political strategies devised to keep order and maintain discipline, to prevent diversity from generating divisions and hostilities among Christians, and, when that failed, to resolve conflict and crisis.

If successful, Church, Book, and Bishop should register a sense of the challenges Christians faced as they sought to order their lives together in this world while awaiting their rewards in the next. And if successful, the books many stories of conflict and resolution should suggest how and why Christians designated certain texts as sacred literature; how and why they interpreted select passages, traditions, and experiences to define and extend the reach of their churches; and how and why they distributed authority within those churches to elders (later priests) and bishops, whom I call executives to distinguish them from itinerant preachers and prophets whose attachments to local settled communities were generally more tenuous.