PRAISE FOR RONALD ROLHEISERS WRITING

Ronald Rolheiser is one of the great Christian spiritual writers of our time.

JAMES MARTIN, SJ, author of Jesus: A Pilgrimage

When Ron Rolheiser writes, it is clear, compelling, and challenging, plus it is about issues that matter to the soul.

FR. RICHARD ROHR, OFM, Center for Action and Contemplation

A master weaver is at work here.

SISTER HELEN PREJEAN, author of Dead Man Walking

Rolheiser dares to ask the hard questions but they are our questionsthe deep ones we are slow to let surface. Then he dares to answer them with clear answers delivered in simple, straightforward language.

FR. BASIL PENNINGTON, OCSO

He is never sentimentaland all the time he is absolutely grounded in reality.

HERBERT ODRISCOLL, author of A Doorway in Time

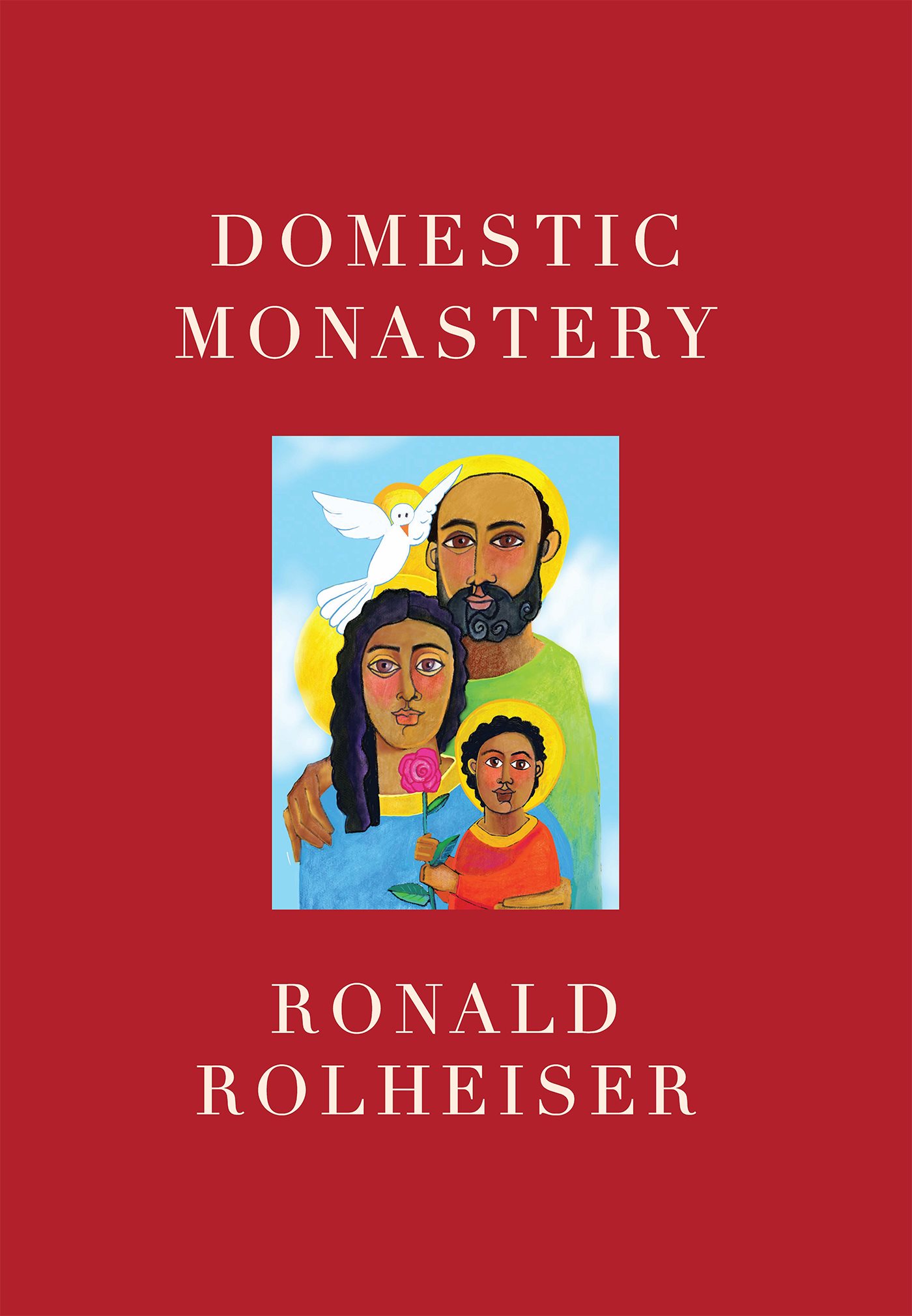

Domestic Monastery

Domestic Monastery

RONALD ROLHEISER

2019 First Printing

Domestic Monastery

Copyright 2019 by Ronald Rolheiser

Cover image copyright 2019 by Brother Michael ONeill McGrath, OSFS

ISBN 978-1-64060-372-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Paraclete Press name and logo (dove on cross) are trademarks of Paraclete Press, Inc.

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in an electronic retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Paraclete Press

Brewster, Massachusetts | www.paracletepress.com

Printed in Korea

CONTENTS

ONE

Monasticism and Family Life

T here is a tradition, strong among spiritual writers, that we will not advance within the spiritual life unless we pray at least an hour a day privately. I was stressing this one day in a talk, when a lady asked how this might apply to her, given that she was home with young children who demanded her total attention.

Where would I ever find an uninterrupted hour each day? she moaned. I would, I am afraid, be praying with children screaming and tugging at my pant legs.

A few years ago, I might have been tempted to point out to her that if her life was that hectic then she, of all people, needed time daily away from her children, for private prayer, among other things. As it is, I gave her different advice: If you are home alone with small children whose needs give you little uninterrupted time, then you dont need an hour of private prayer daily. Raising small children, if it is done with love and generosity, will do for you exactly what private prayer does.

Left unqualified, that is a dangerous statement. It, in fact, suggests that raising children is a functional substitute for prayer.

However, in making the assertion that a certain servicein this case, raising childrencan in fact be prayer, I am bolstered by the testimony of contemplatives themselves. Carlo Carretto, one of the twentieth centurys best spiritual writers, spent many years in the Sahara Desert by himself praying. Yet he once confessed that he felt that his mother, who spent nearly thirty years raising children, was much more contemplative than he was, and less selfish. If that is true, and Carretto suggests that it is, the conclusion we should draw is not that there was anything wrong with his long hours of solitude in the desert, but that there was something very right about the years his mother lived an interrupted life amid the noise and demands of small children.

St. John of the Cross, in speaking about the very essence of the contemplative life, writes: But they, O my God and my life, will see and experience your mild touch, who withdraw from the world and become mild, bringing the mild into harmony with the mild, thus enabling themselves to experience and enjoy you (The Living Flame, 2.17).

In this statement, John suggests that there are two elements crucial to the contemplatives experience of Godnamely, withdrawal from the world, and the bringing of oneself into harmony with the mild. Although his writings were intended primarily for monks and contemplative nuns who physically withdraw from the world so as to seek a deeper empathy with it, his principles are just as true for those who cannot withdraw physically.

But they,

O my God and my life,

will see and experience

your mild touch,

who withdraw

from the world and

become mild,

bringing the mild into

harmony with the mild,

thus enabling themselves

to experience

and enjoy you

ST. JOHN OF THE CROSS

Certain vocationsfor example, raising childrenoffer a perfect setting for living a contemplative life. They provide a desert for reflection, a real monastery. The mother who stays home with small children experiences a very real withdrawal from the world. Her existence is certainly monastic. Her tasks and preoccupations remove her from the centers of social life and from the centers of important power. She feels removed.

Moreover, her constant contact with young children, the mildest of the mild, gives her a privileged opportunity to be in harmony with the mild and learn empathy and unselfishness. Perhaps more so even than the monk or the minister of the gospel, she is forced, almost against her will, to mature. For years, while she is raising small children, her time is not her own, her own needs have to be put into second place, and every time she turns around some hand is reaching out demanding something. Years of this will mature most anyone. It is because of this that she does not need, during this time, to pray for an hour a day. And it is precisely because of this that the rest of us, who do not have constant contact with small children, need to pray privately daily.

We, to a large extent, do not have to withdraw. We can, often, put our own needs first. We can claim some of our own time. We do not work with what is mild. Our worlds are professional, adult, cold, and untender. Outside of prayer, we run a tremendous risk of becoming selfish and bringing ourselves into harmony with what is untender. Monks and contemplative nuns withdraw from the world to try to become less selfish, more tender, and more in harmony with the mild. To achieve this, they pray for long hours in solitude.

Mothers with young children are offered the identical privilege: withdrawal, solitude, the mild. But they do not need the long hours of private prayerthe demands and mildness of the very young are a functional substitute.

Next page