Published in 2021 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2021 by The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kent, Deborah, author.

Title: Dark days in Salem: the witchcraft trials / Deborah Kent.

Description: New York: Rosen Publishing, 2021. | Series: Movements and

moments that changed America | Includes bibliographical references and

index. | Audience: Grades 6-12.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019011184 | ISBN 9781725342033 (library bound) | ISBN

9781725342026 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: WitchcraftMassachusettsSalemHistoryJuvenile

literature. | Salem (Mass.)Church history17th centuryJuvenile

literature. | Trials (Witchcraft)MassachusettsSalemHistoryJuvenile

literature.

Classification: LCC BF1576 .K46 2021 | DDC 133.4/3097445dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019011184

Printed in the United States of America

Portions of this book originally appeared in Witchcraft Trials: Fear, Betrayal, and Death in Salem.

Photo Credits: Cover, p..

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #BSR20. For further information contact Rosen Publishing, New York, New York at 1-800-237-9932.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Witches seem to be everywhere in downtown Salem, Massachusetts. On street corners, costumed witches pose for photos and cackle jauntily at passersby. Tourists flock to the citys witch museums and take witch-related walking tours. Each October, a month-long festival called Haunted Happenings culminates in a spectacular Halloween parade. Even Salems fire engines sport the logo of a witch in a pointed hat riding on a broomstick.

Witchcraft is big business in Salem today, but there was nothing festive about the seven-month period of terror, accusation, and death that engulfed Salem and many of the neighboring towns in 1692. Salem was the scene of one of the strangest and most tragic episodes in the history of Englands North American colonies. By the time the witchcraft hysteria was over, twenty women and men had died and dozens more languished in prison.

The Salem witchcraft trials took place more than three hundred years ago, yet they hold a deep fascination for the public today. Perhaps the lure of something mysterious and forbidden draws people to the scene of the witch drama.

The Salem Witch Museum brings the witchcraft panic to life through stage sets with life-size figures and a narration of the 1692 witchcraft trials. Presentations are provided in eight languages.

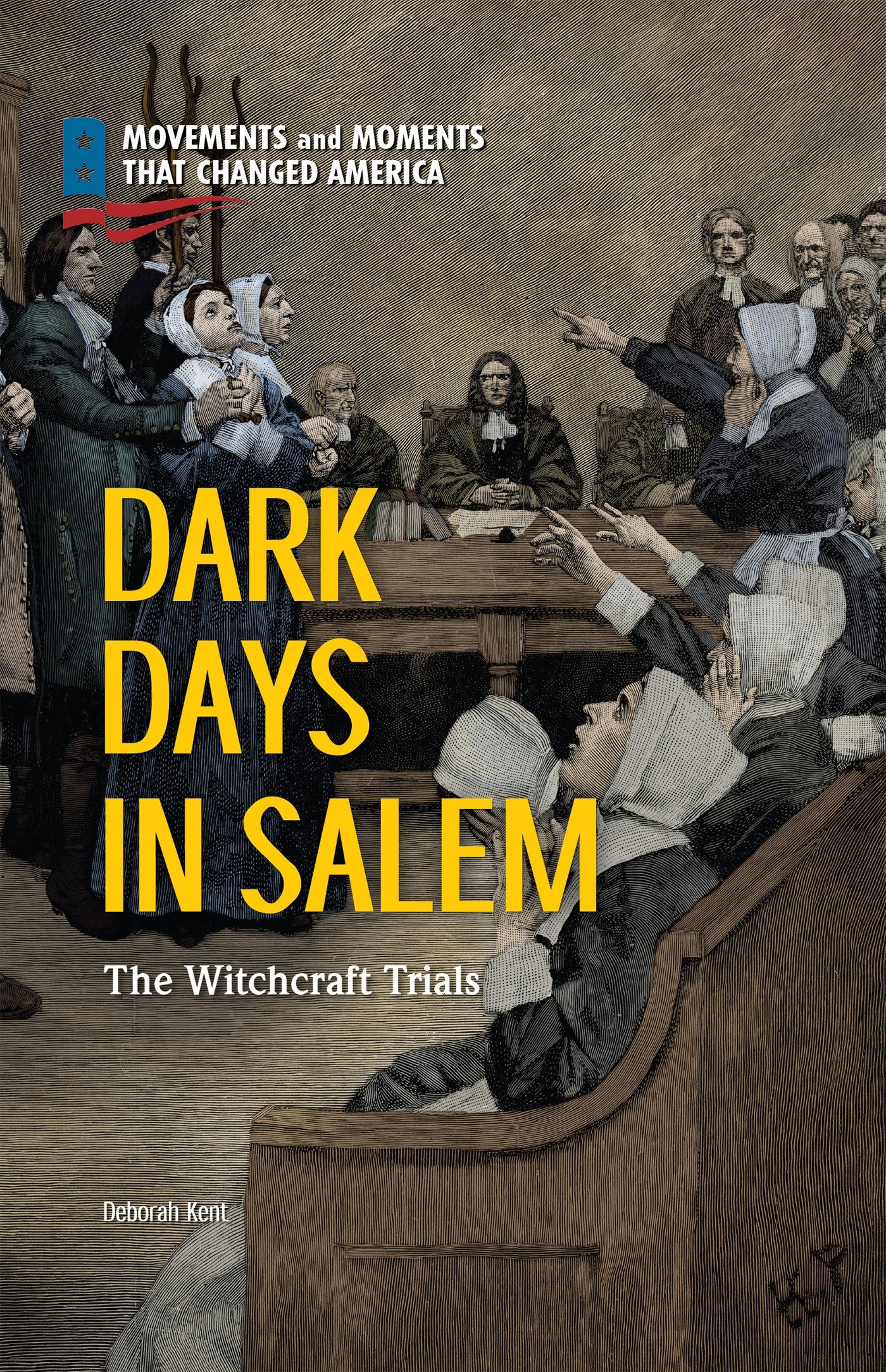

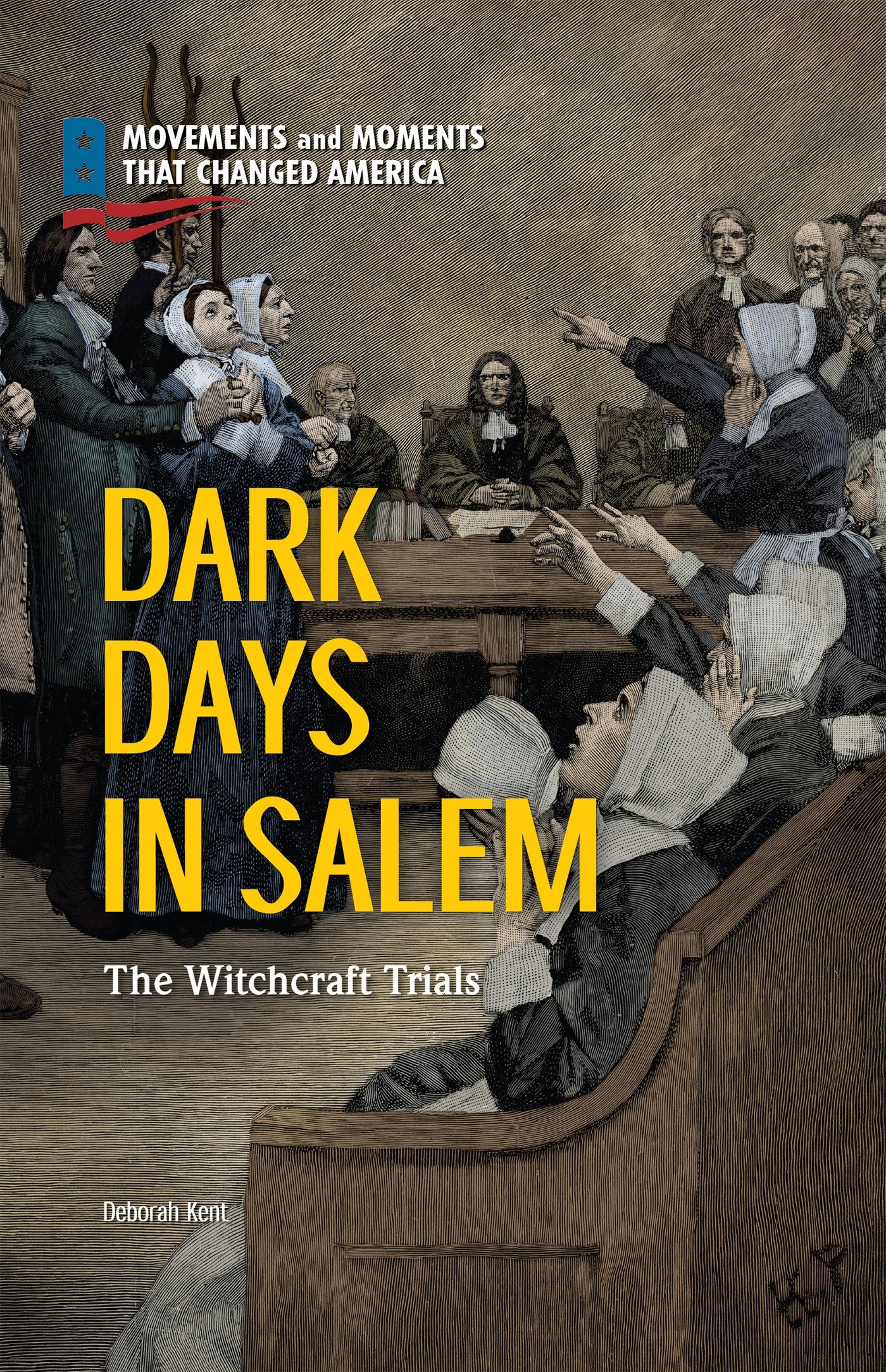

Many nineteenth-century artists and writers became fascinated with the Salem witchcraft story. In this engraving, American artist Howard Pyle (18531911) depicts a courtroom scene in which two suspected witches are on trial.

Perhaps the suggestion of evil, shrouded safely in the past, gives visitors a delicious tingle of fright.

Much of the witchcraft memorabilia in present-day Salem is designed to appeal to tourists, but a few historic landmarks survive to tell the grim tale. The two-story frame house that was the home of Jonathan Corwin still stands at 310 Essex Street. Corwin was one of the judges who presided over the witchcraft trials and sentenced several of the convicted witches to death. Another Salem landmark directly related to the witchcraft frenzy is Gallows Hill, where it is believed that many of the convicted witches faced the hangmans noose.

The story of the Salem witch hunt raises some troubling questions. Why was a quiet community seized by such fear and hatred that neighbor turned against neighbor and children against parents? Why did total strangers assail one another with deadly accusations? Why did religious and civic leaders fail to restore calm, instead stirring the hysteria to even greater intensity?

The events that took place in Salem in 1692 are not unique in human history. Under certain circumstances anxiety can turn into fear, and fear can erupt into panic. Innocent people can become targets of blame and retribution. The term witch hunt has entered the vocabulary to describe any instance when a furor of accusation takes place. The story of Salem has a great deal to teach society about how fear can conquer reason and people branded as other can become the victims of persecution. Perhaps the lessons of Salem may help humanity steer away from a similar tragedy in the future.

1

1

LITTLE SORCERIES

During the winter of 1692, nine-year-old Betty Parris and her cousin, eleven-year-old Abigail Williams, spent their evenings in the kitchen. The kitchen was the only room in the house where a fire was kept burning. It was the only place where the girls found a bit of comfort after the long, cold day.

Trouble at the Parsonage

Salem Village was a lonely place, especially during the winter. The village was a collection of scattered farms amid trackless woods. The tavern and the church, or meetinghouse, were the only places where people could gather. Officially, Salem Village was part of Salem Town, 7 miles (11 kilometers) away. Yet the village and the town had little in common. Salem Town was a busy seaport. Ships brought goods and news from Europe and the West Indies. Tucked away in the woods, Salem Village was separated from the town by a two-hour journey on horseback. After a heavy snow, the trip was almost impossible.

This print shows a view of Salem Village as it might have appeared in the late seventeenth century.

Betty Parriss father, the Reverend Samuel Parris, served as the Puritan minister of Salem Village, and the family lived in the village parsonage. The parsonage was a four-room cottage with a small attached shed at the back. The family consisted of the Reverend Parris; his wife, Elizabeth; their three children; and Parriss orphaned niece, Abigail.

In addition to the Parris family, the household included two live-in servants, a couple named Tituba and John Indian. At the time, slavery was permitted in Massachusetts, and both Tituba and John were enslaved. Historians estimate that about two hundred enslaved people lived in Massachusetts in 1690, most of them of African origin. Some Native Americans also were enslaved. The Reverend Parris had bought Tituba on the Caribbean island of Barbados, where he lived for several years before settling in Massachusetts. Some historians think she belonged to the Arawak people, a group native to the Caribbean region. John Indian seems to have come from one of the Native American tribes that lived in New England.