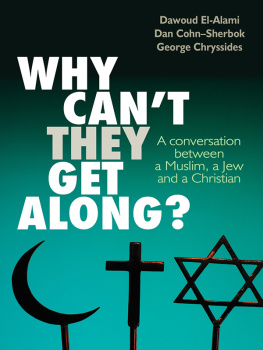

INSIGHTS FROM

THE RISALE-I NUR

Said Nursis Advice for Modern Believers

Thomas Michel

Copyright 2013 by Tughra Books

16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including

photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Published by Tughra Books

345 Clifton Ave., Clifton,

NJ, 07011, USA

www.tughrabooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

Digital ISBN: 978-1-59784-678-3

Printed by

alayan A.., Izmir - Turkey

Said Nursi: The Most Influential

Muslim in Modern Turkey

Said Nursi is probably the most influential Muslim thinker in Turkey in the 20 th Century. It has been estimated that between 8 and 13 million Muslims regularly study his 6000-page commentary on the Quran entitled the Risale-i Nur , or Message of Light, on which Nursi worked for more than 40 years. People dont just read the Message of Light once and go on to something else; the book forms the basis of an ongoing program of spiritual growth.

In the city of Ankara, where I was living until a short time ago, there are about 90 groups who gather every week in faith-sharing sessions to study and discuss Nursis Message of Light. In my experience, these sessions appear to be especially attractive to professionals in medicine and engineering and, in Ankara, the capital, to civil servants in various government ministries. They come together in the evening and read a passage from the Risale-i Nur ; the reading is followed by a discussion guided by one of the experts in the book in order to apply the insights found in this enormous book to their personal and social lives. These experts are often people who have dedicated their whole lives to the study of the Quran as elucidated in Said Nursis commentary.

I first came to know about Nursi and his Quran commentary from my students. In 1985, the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, where I was teaching, signed an academic agreement with Ankara Universitys Theology Faculty which entailed an exchange of professors. Until today, every year, a Turkish professor goes to Rome to teach Islamic studies, and I or another professor from Rome teaches Christian theology in Turkey. So, in 1986, after I began teaching in Ankara, some of my students introduced me to the writings of Said Nursi. In those days, very little of the Message of Light had been translated into English, so with my students in the evenings I began to read those parts that had been translated and published as small pamphlets.

Several aspects of his thought attracted me immediately. Long before others were speaking of it, Nursi urged unity between his followers, students of the Risale-i Nur , and true Christians who were striving to follow the teachings and example of Jesus. He didnt write about dialogue, because the word wasnt yet in current usage; but he used an even stronger term, unity , encouraging true Muslims and Christians to achieve a kind of unity of purpose. Writing before World War I and again after World War II, amidst tensions and enmity between Muslims and Christians, Nursi proposed that the two communities should avoid disagreements and polemics and give a united witness of faith to a world that was suffering from the growth of aggressive atheism. These were the years when the Soviet communist system was advancing through Eastern Europe and even threatening Western European nations like Greece, Italy, and France.

Nursi called for unity and cooperation between the two communities already fifty years before the Vatican II called upon Christians and Muslims to recognize that they should move beyond the conflicts of the past and work together for the common good to build peace, establish social justice, defend moral values, and promote true human freedom. As a Christian whose theological attitudes toward Muslims were formed by the teachings of the Second Vatican Council, I was attracted to learn more about Said Nursi as someone who shared a similar vision to that later proposed by the Catholic Church.

Another aspect of Nursis thought I find attractive is his strong rejection of violence. Although as a youth he fought in the Ottoman army to repulse the Russian invasion of Turkey in World War I, he later came to the conclusion that the days of the jihad of the sword are over. The only appropriate way for Muslims to struggle for their beliefs was the jihad of the word or the jihad of the pen, that is, through personal witness, persuasion, and rational argument.

Nursi was convinced of the primacy of love in Islam. That which is most worthy of love, he wrote, is love, and that most deserving of our enmity is enmity. It is love and loving, he went on, that render peoples social life secure and lead to happiness. The time for enmity and hostility is finished, he concluded. Nursi wrote these words 100 years ago this year, in 1911, in a Friday sermon he delivered to several thousand worshipers at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. That sermon, which has been translated and published in many languages, has become one of the classics of modern Islamic spirituality.

I cant do justice to all the topics treated in the 6000 pages of the Risale-i Nur . Nursi has included treatises directed at the youth, the aged, the sick, prisoners, and victims of disasters. He has a special concern to defend belief in the afterlife, to reconcile the teachings of Islam with science and technology. Some of the most beautiful parts of the Risale -i Nur are his contemplative reflections on Gods attributes of power, mercy, and love as they are evident in nature and the created universe.

For most of the 20 th Century, the Turkish Republic was governed by leaders influenced by the European Enlightenment who regarded religious faith as backward, suitable for simple people and primitive societies but incompatible with modern science and an obstacle to be overcome if the nation is to progress. A dictum often repeated in the intellectual atmosphere of the day held that religion was doomed to wither away as modern people came to accept a scientific understanding of life and society. In this, the thinking of Atatrk, nn and their Turkish associates was not much different from that of Garibaldi, Cavour and the other leaders of the Italian Risorgimento, and those whose ideas shaped the Mexican and Russian revolutions.

Faced with this climate of suspicion, many Muslim leaders in Turkey reacted by condemning the political and military authorities as godless agents of Satan. Some went so far as to revolt, which in turn drove the authorities to persecute the religious scholars as enemies of the state. In this conflictual situation, Nursi relied on rational argument. He criticized the government authorities on religious grounds but did not foment rebellion. The legacy of European modernity, he said, has a positive aspect and a negative one. He had no argument with the fruits of science and technology; these he saw as beneficial to humanity. But he felt that by cutting people off from their religious heritage, the leaders were spiritually impoverishing the people. Through its policy of radical secularism, the government was depriving Turkish society of the guidance, the solace, and the hope that comes from faith, so that religious adherence was reduced to a private collection of beliefs and rituals.

One of the insights of Nursi that has had much influence on his followers is his view that the real enemies of Muslims are not one or another group of people. Rather, he said, the real enemies of humankind are three: ignorance, poverty, and disunity , and it is against such enemies that Muslims must do jihad with the weapons of knowledge, science, and hard work.