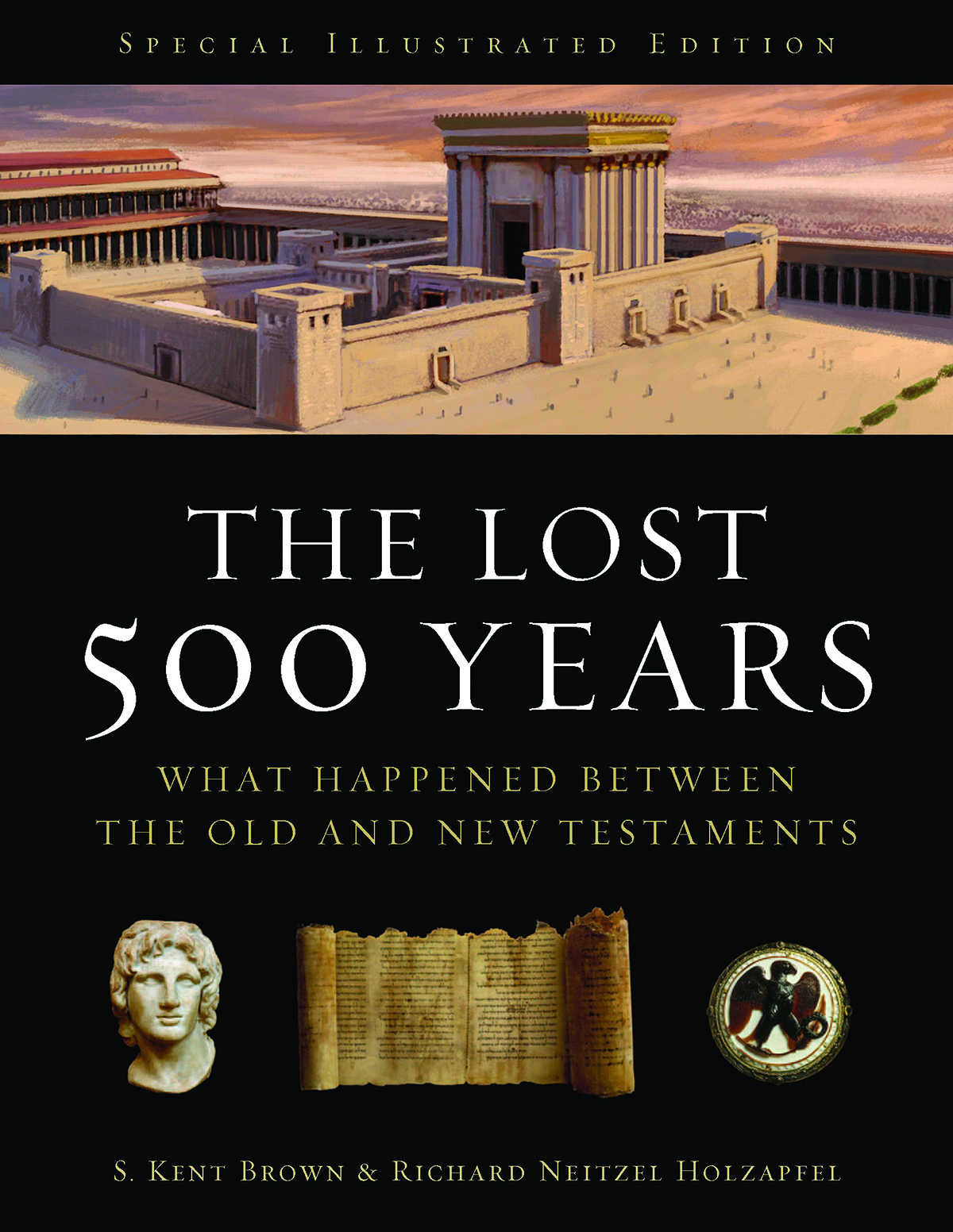

2012 S. Kent Brown; Richard Neitzel Holzapfel.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, Deseret Book Company, P.O. Box 30178, Salt Lake City Utah 84130. This work is not an official publication of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The views expressed herein are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the position of the Church or of Deseret Book. Deseret Book is a registered trademark of Deseret Book Company.

Front cover images:

Herods Temple, cover illustration by Brandon Dorman.

Alexander Bust, third century B.C.; Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com. By all odds, Alexander was the most influential person who lived during the intertestamental period. He grew up a prince in Macedonia (356323 B.C.), a region north of Greece proper, where he received a Greek education. He came to power upon the death of his father, Philip, in 336 b.c.

Temple Scroll, first century B.C.; Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com. The Temple Scroll, the largest surviving text of the Dead Sea Scrolls, offers a first-person commandment to build the temple, including its dimensions. It also preserves laws that governed a persons standing before God, which differ from those of the later rabbis.

Roman Cameo, 27 B.C.; Nimatallah/Art Resource, NY. This cameo depicts a Roman eagle with symbols of victory relating to the end of the civil war under Augustus.

Back cover images:

Antigonus Coin, 4037 B.C.; Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com. One of the best-recognized Jewish coins depicts a Jewish menorah and was minted by the last Hasmonean claimant to the throne (supported by the Parthians). He was eventually deposed by Herod the Great, who returned from Rome as the King of Judea.

Greek and Persian Warrior Vase, mid-fifth century B.C.; Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY. This vase depicts a hand-to-hand struggle between a Greek and a Persian soldier and underscores the long conflict between the two nations. From the artistic representation of these soldiers it is clear that Greek soldiers relied more on their skills than on extensive armor to protect themselves. The style of painting is red-figured oenochoe on a black background. Alexander the Great finally ended the conflict by defeating King Darius and the Persian army at the Battle of Issus in Asia Minor in 333 b.c.

Oil Lamp, second century B.C.; Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY.

An Archer, Detail from Procession, 515 B.C.; Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY. The fine detail of this archer, one of several in a procession depicted on the palace wall of the Persian king, Darius the Great (491486 B.C.), reveals the hair style that men wore in the early fifth century, including the band that bound the hair, as well as the cut of the beard. Persian archers also carried spears for protection, though not shields. The arrows in the quiver should probably be thought of as round rather than flat. Otherwise, the number of arrows in the quiver would only be around ten.

Ptolemy Cameo, 278 B.C.; Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY. This graceful cameo of Ptolemy II and his queen points to the era when the Old Testament was translated from Hebrew into Greek.

Jericho Mikveh, c. 30 B.C.; Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com. Ritual purification, as represented in this mikveh at Jericho, became the dominant feature of religious life away from the temple and synagogue.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brown, S. Kent

The lost 500 years : what happened between the Old and New Testaments /

S. Kent Brown, Richard Neitzel Holzapfel.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-10 1-59038-584-5 (pbk.)

ISBN-13 978-1-59038-584-5 (pbk.)

1. JudaismHistoryPost-exilic period, 586 B.C.210 A.D. 2. JewsHistory586 B.C.70 A.D. I. Holzapfel, Richard Neitzel.

II. Title.

BM176.H564 2006

220.95dc222006006522

Printed in the United States of America

R. R. Donnelley, Allentown, PA

10987

For Karilynne, Julianne,

Heather, Shoshauna, and Scott

S. Kent Brown

For Zanna and Brian,

my daughter and son-in-law

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel

Front Matter

Preface

Even the most casual reader of the Bible senses vast differences in tone, texture, and doctrines between the Old and New Testaments. After reading Malachi and then turning to Matthews Gospel, we sense that more than unspoiled time has passed lazily between the end of the Old Testament period and the beginning of the New Testament. The nearly five centuries that separate the two parts of the Bible represent far more than a mere chronological divide. They also represent a hefty cultural gap.

By almost any account, an entirely new group of people rises into view within the pages of the New Testament in contrast to the group portrayed in the Old. Certainly the people, one group in the Old Testament and another in the New, inhabited the same geographical area, shared a basic religious point of view, and were of the same families and clans. Yet these two chronologically separate peoples seem deeply dissimilar in significant ways.

One obvious example of differences that we encounter between the Old and New Testaments appears in common personal names. In the Old Testament, we become familiar with the names Jacob, Joshua, Miriam, Hannah, and Elijah. In the New Testament, we read regularly of James, Jesus, Mary, Anna, and Elias. In actuality, the New Testament names are the Greek equivalents of the same names found in the Hebrew Old Testament. The case is much like the names of Paul and Pablo. They are the same name, but one is English and the other is Spanish.

However, the major differences between the Old and New Testaments do not lie simply in language. The Old Testament has come down to us in Hebrew, with a few Aramaic sections, and the New Testament comes to us in Greek. Nevertheless, the central difference between the peoples who lived at the end of the Old Testament period and those at the beginning of the New was the ever-shaping, ever-renewing passage of time. Those nearly five centuries brimmed with far-reaching changes that included periods of crippling crisis, brilliant inventiveness, cautious adaptation, and painful transition. By all odds, the major influence in that era arose from Hellenization (from Hellas, the term for Greece). By definition, Hellenization sought to repackage the world as Greek. Making its relentless influence felt initially with the coming of Alexander the Great into the Near East in the late fourth century B.C., Hellenization affected people in profound ways and explains many of the differences in tone and texture between the Old and New Testaments.

This book, The Lost 500 Years: What Happened between the Old and New Testaments, is an updated, expanded, and illustrated edition of our earlier work, Between the Testaments: From Malachi to Matthew (2002). In The Lost 500 Years, we attempt to connect the Old and New Testaments by opening a window onto events that unfolded from the time that members of the covenant people returned from their Babylonian exile, not long before the end of the Old Testament age, to the period when Jews lived under Roman dominion at the beginning of the first century A.D., coinciding with the beginning of the New Testament era. Admittedly, one of the nettlesome challenges that face any student of this period is the lack of sources for vast expanses of time. For these gaps, we have tried to be restrained in what we can legitimately conclude.