Published in 2015 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2015 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means-electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise-without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 9804454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #WS14CSQ

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stevens, Madeline.

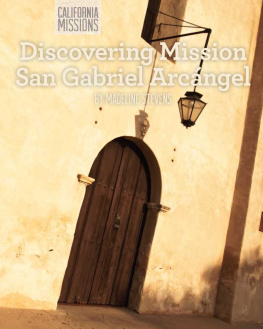

Discovering Mission San Gabriel Arcangel / Madeline Stevens. pages cm. (California missions)

Includes index.

ISBN - - 62713 - 115-5 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-62713-117-9 (ebook)

1. Mission San Gabriel Arcangel (San Gabriel, Calif.)HistoryJuvenile literature. 2. Spanish mission buildingsCalifor-niaSan Gabriel RegionHistoryJuvenile literature. 3. FranciscansCaliforniaSan Gabriel RegionHistoryJuvenile literature. 4. Gabrielino IndiansMissionsCaliforniaSan Gabriel RegionHistoryJuvenile literature. 5. CaliforniaHistoryTo 1846Juvenile literature. I. Title. F869.M655M34 2015

. dc

2014005325

Editorial Director: Dean Miller Editor: Kristen Susienka Copy Editor: Cynthia Roby Art Director: Jeffrey Talbot Designer: Douglas Brooks Photo Researcher: J8 Media Production Manager: Jennifer Ryder-Talbot Production Editor: David McNamara

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of: Cover photo by Eddie Brady/ Lonely Planet Images/Getty Images; Jason O. Watson (USA: California photographs)/Alamy, 1; John Crowe/Alamy, 4; BBVA Collection/File:Charles III, 1786-88.jpg/Wikimedia Commons, 6; Marilyn Angel Wynn/Nativestock/Getty Images, 7; Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, 8-9; 2014 Pentacle Press, 12; North Wind Picture Archives/ Alamy, 13; Courtesy California Missions Resource Center (CMRC), 15; Courtesy CMRC, 16; Courtesy CMRC, 17;

Pentacle Press, 20; Karin Hildebrand Lau/Alamy, 22; Culture Club/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, 25; Edwin J. Hayward and Henry W. Muzzall/File:Juana Maria (Hayward & Muzzall).jpg/Wikimedia Commons, 28; Courtesy CMRC, 32-33; Robert A. Estremo/File:Mission San Gabriel 4-15-05 6611.JPG/Wikimedia Commons, 34; Robert A. Estremo/File:Mission San

Gabriel 4-15-05 6611.JPG/Wikimedia Commons, 41.

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

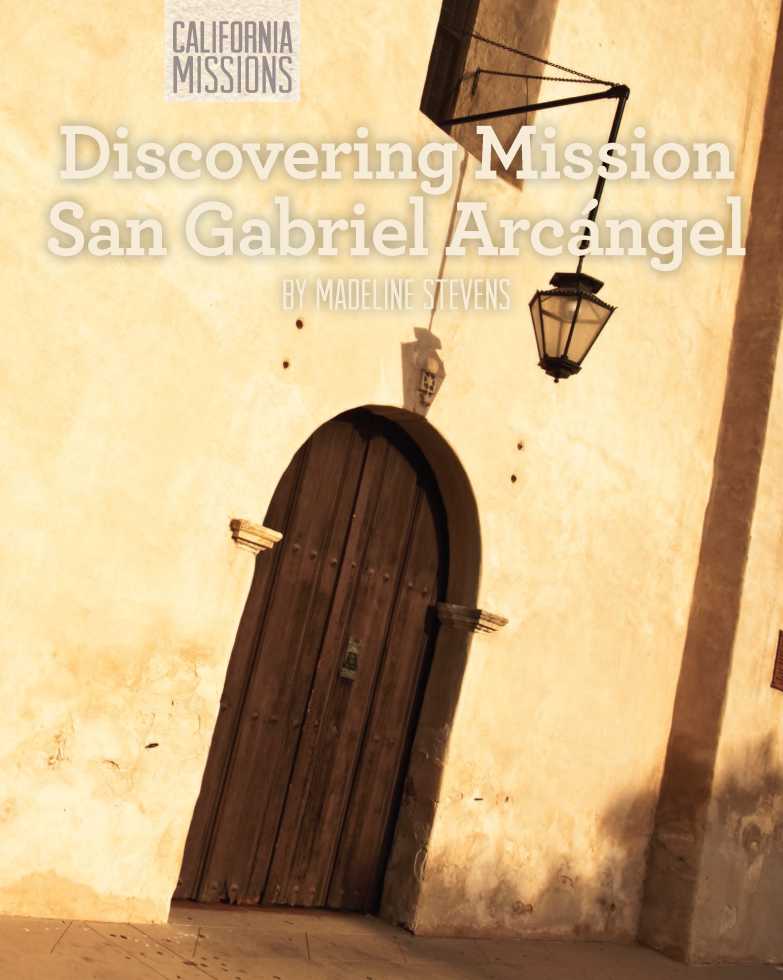

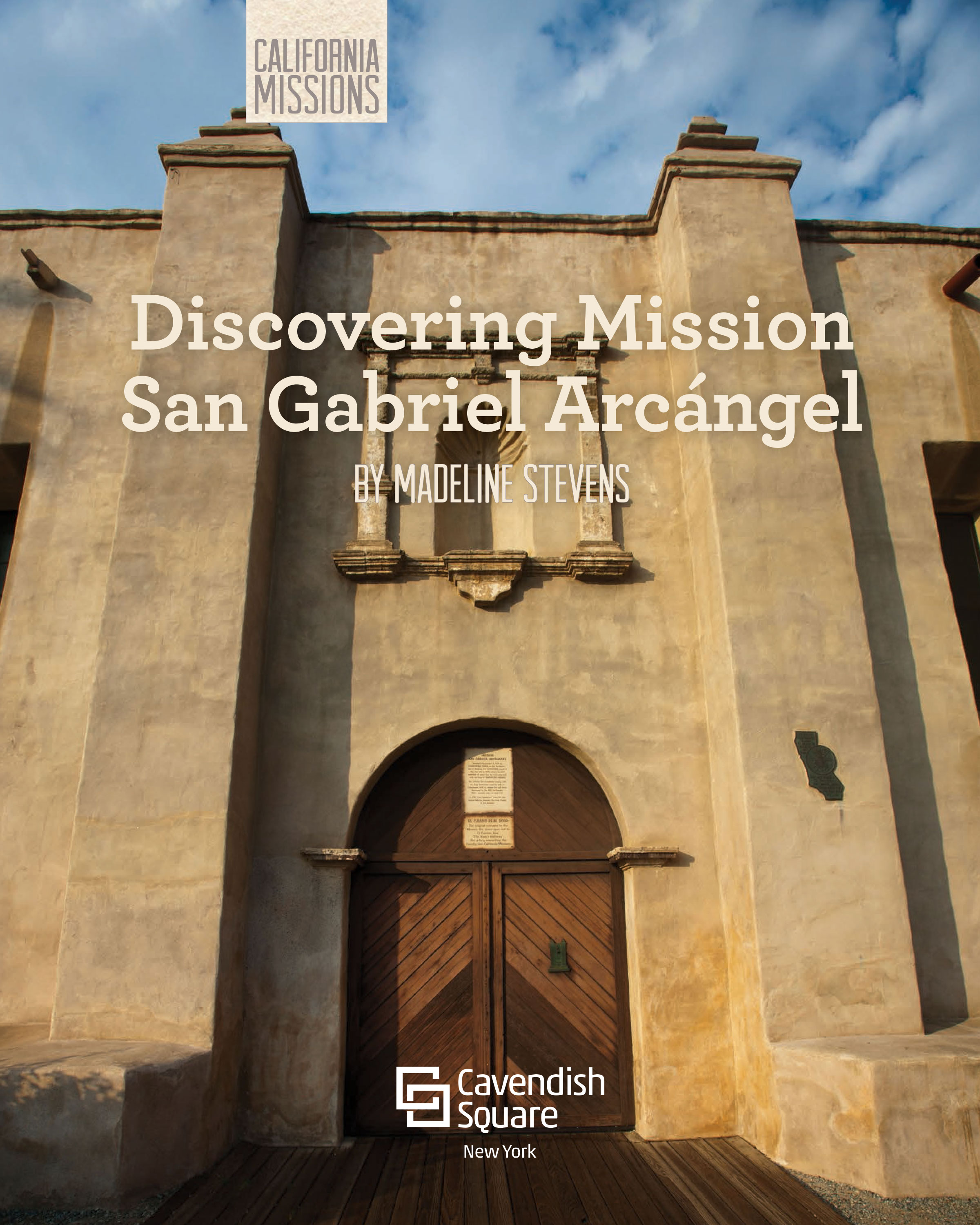

Tucked away in downtown San Gabriel stands a large fortress-style church building that looks somewhat out of place in modern California. Yet the structure played a primary role, both good and bad, in the history of the region. Named for Saint Gabriel, Holy Prince of Archangels, Mission San Gabriel Arcangel's story tells of struggle, accomplishment, difficulties, and the founding of one of the great cities in North America.

staking a claim

The Spanish first arrived along the coast of what they called Alta,or upper, California in 1542. Explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo sailed out of Navidad, near Manzanillo, Mexico, on June 24, to search for legendary wealthy cities and a water route from the North Pacific to the North Atlantic. Neither existed. Cabrillo discovered the Bay of San Diego on September 28. He stopped along the shores of Santa Catalina and San Pedro on October 6, and the Tongva, the region's indigenous people, canoed out to meet him. They invited him to land but he declined. Members of his expedition later reached as far north as today's Oregon before returning to Navidad on April 14, 1543.

In the 1760s, King Carlos III sent friars and soldiers to Alta California to start missions.

By the 1760s, King Carlos III of Spain wanted to ensure his claim on this land before Russian or English people settled there. In 1768, the king told the viceroya person chosen to rule for the king in a new landof New Spain (today's Mexico) to start settling the northern frontier of New Spain, using the mission system. The king sent his officer, Inspector General Jose de Galvez, to help. Spain had already used the mission system to take over land in New Spain, Florida, Texas, and Baja, or lower, California.

In the spring of 1769, the governor of Baja California, an army captain named Gaspar de Portola, led a group of soldiers, missionaries, and some Christian Native Americans from the Baja California missions into Alta California. Some traveled in three ships. Others, including the president of the missions, Fray Junipero Serra, traveled the 715 miles by land. Their destination was the San Diego harbor, discovered more than 225 years earlier by Cabrillo. Nearly half of the 219-member expedition died or deserted before reaching their destination in early July. One of the three ships was lost at sea.

On July 16, 1769, Fray Serra founded the first of the twenty-one missions near the harbor. He named it San Diego de Alcala.

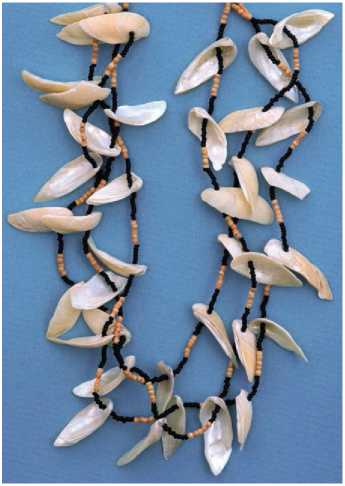

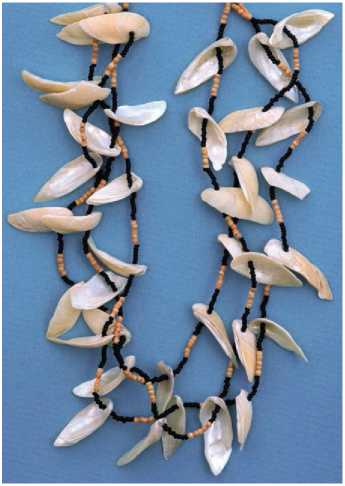

Like the Tongva, the Chumash used seashells to make jewelry.

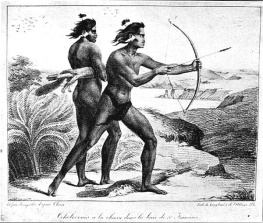

The Native Californians near Mission San Gabriel Arcangel belonged to the Tongva tribe. There were many villagesas many as thirty-one known sites spread over a wide area. There were an estimated 5,000 Tongva in the region when the Spanish arrived. Each village was ruled by a group of elders. The Tongva leaders could be men or women, and were called wots. Each Tongva village also had a religious leader and healer called a shaman.

ocean traveler

The Tongva and the Chumash, their neighbors to the north and west, were among the few indigenous populations that navigated the ocean. They made plank canoes called tiats or tomols, which were up to 30 feet long. The tomols were large enough to hold twelve men and their goods, and strong enough for ocean travel. These canoes were made from planks held together with hemp or dowels. They were then coated with pine pitch and tar, which could be found at the La Brea Tar Pits, or asphaltum that washed ashore from natural oil seeps.