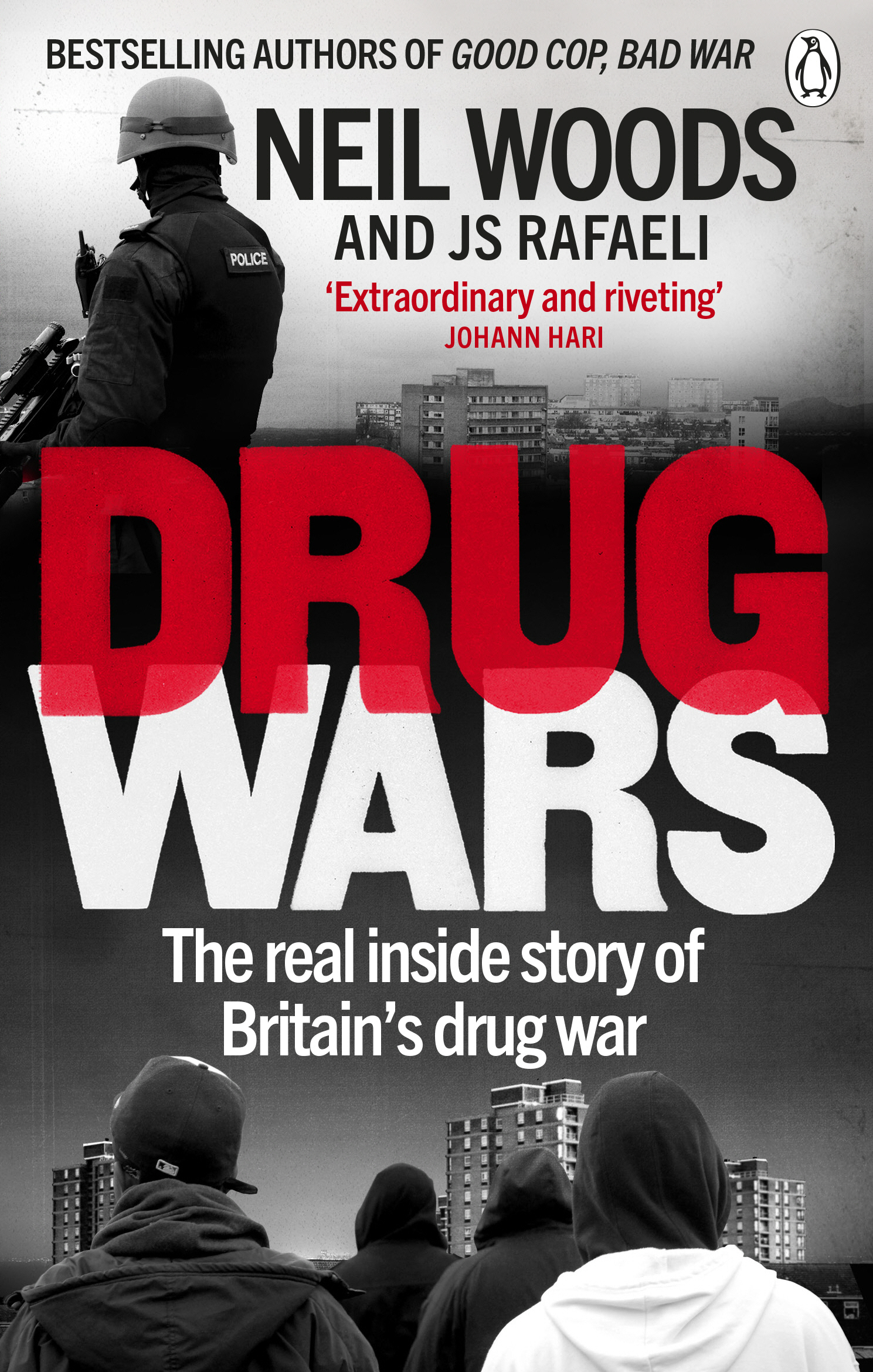

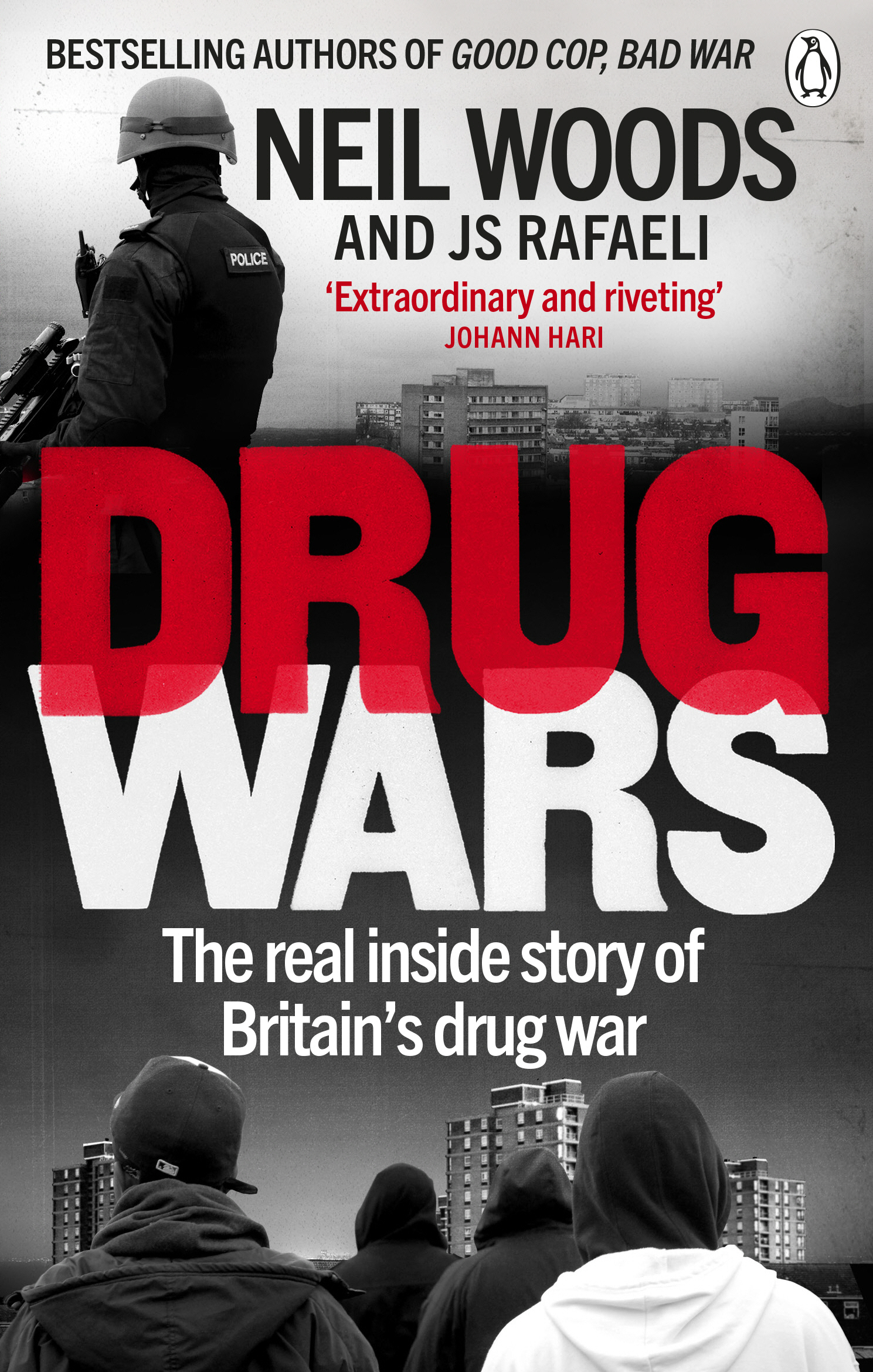

NEIL WOODS

& JS RAFAELI

Contents

About the Authors

Neil Woods spent fourteen years (1993-2007) infiltrating drug gangs as an undercover police officer befriending and gaining the trust of some of the most violent, unpredictable criminals in Britain. With the insight that can only come from having fought on its front lines, Neil came to see the true futility of the War on Drugs that it demonises those who need help, and only empowers the very worst elements in society. Neil is on the board of LEAP (Law Enforcement Action Partnership) in the US and is the Chair of LEAP in the UK. LEAP is an organisation made up exclusively of law enforcement professionals, past and present, who campaign for drug law reforms. Neil has also starred in Channel 4 Drugs Live.

JS Rafaeli is a writer and musician based in London. He is the author of Live at the Brixton Academy, worked closely with Neil Woods on Good Cop, Bad War and is a frequent contributor to Vice.

Dedicated to all those around the world who fight against unjust laws.

Preface

by Neil Woods

The observation van is parked on a rough, dead-end street in Leeds, running surveillance on a high-level Bradford drug dealer. Suddenly, the van is surrounded by men in balaclavas. It is tied shut, doused in petrol and set on fire. The two cops inside barely get out alive.

It was no accident that the gangsters knew there was an obs van outside their safe house that night. They had moles inside the police feeding them information.

That incident was never reported in the press, but I remember the operation well. The thought of those two officers trapped inside the burning vehicle stuck with me it forced me to once again ask myself a gnawing question. How has it come to this? How has it got to the point where the police come under attack because their own systems have been corrupted?

This wasnt the first time on the force Id experienced high-level corruption. When I was working under cover in Nottingham, my own unit had been infiltrated by the sociopathic drugs kingpin, Colin Gunn.

Gunn had hired a 19-year-old kid named Charles Fletcher to join the police with specific instructions to get into CID. For years, Gunn paid Fletcher 2,000 a month on top of his police salary to pass on intelligence about ongoing investigations.

When I confronted my superiors about this I was met with a shrug. With so much money in the drugs game, how can corruption not happen? It had got to the point that with drug investigations, police corruption had just become an accepted part of the game. How has it come to this?

On another major operation, the first lawful order we received was that under no circumstances were we to speak to anyone from Greater Manchester Police and that if anyone from GMP approached us, we were to immediately report it. We were forced to work under the assumption that a major British police force was so riddled with moles and informants that any contact with them whatsoever was suspect. How has it come to this?

That question stuck with me throughout my final years on the force. It continued to trouble me even after I had left the police and tried to dedicate my life to undoing some of the harm that I had caused. Then we published the book Good Cop, Bad War.

The response to Good Cop hit me for six. We started receiving letters and emails from all over the country and from around the world. There were messages from cops and ex-cops; addicts and family members of addicts; drug dealers and serving prisoners who had read the book in the prison library. These were all people who had experienced the War on Drugs at first hand from both sides of the battle line.

Somehow, what we had written in Good Cop resonated with their experience. This outpouring of support and encouragement was both humbling and profoundly inspiring. Then, one letter came through that stopped me in my tracks.

It was from a young man named Adam, whose parents had both been intravenous heroin users. Adam spent his childhood caught in the chaotic mess of overdoses and arrests that often define the life of drug users under a system of prohibition. He spoke of witnessing the beatings his parents received at the hands of ruthless gangsters. He remembered seeing the desperation and shame in their eyes, and of knowing, even as a child, that what they needed was help, support, and understanding, not prison and judgement.

Adam wrote of how he watched the arms race of the War on Drugs unfold how it got more and more violent, more and more difficult. He wrote of how this war wasnt going to be won with force, arrests, prison and isolation.

He wrote of having to watch his own mother being forced to drink petrol over a 20 drug debt.

Once again, that question how has it come to this?

In the face of Adams letter, and hundreds more like it, I decided I would finally try to answer that question.

We didnt get here by accident. The situation Adam, myself and thousands of others caught up in the War on Drugs have found ourselves in, is the result of very specific decisions, taken over decades. These decisions need to be looked at.

The British War on Drugs is almost 60 years old. To explain how it functions, you need to look back into its roots. This is a story that has never been told until now.

On Good Cop, Bad War, I worked closely with the writer JS Rafaeli. Throughout that process, we had begun to ask questions about the wider meaning of the personal story we were telling. How did the War on Drugs develop? What impact has it had on British policing and law enforcement? What can this tell us about the relationship between the individual and the state? On a personal level, considering these questions turned out to be invaluable in helping me begin to understand and process the PTSD from which I had suffered since leaving the police.

So, we decided to take on this new project together. By combining my inside perspective of the police with JSs skills as a historian and journalist, we could confidently approach this hugely complex story. This book is a completely equal, joint effort between us and has been an incredibly challenging, but rewarding, process for us both.

The first thing we decided was that we needed to talk about people. All too often when discussing drug policy, the conversation gets caught up in statistics and vague political ideas. Its academics arguing with politicians arguing with cops and everyone loses sight of the fact that behind the numbers lie real people, with real stories.

We wanted these voices to be heard. We wanted them brought back into the conversation. So, we spent months going up and down the country interviewing drug dealers, cops, addicts, health workers, activists and politicians getting to the truth of what the British War on Drugs has meant to the people who actually fought it.

We met some extraordinary people. We cannot thank each and every one of them enough for their courage and generosity in sharing their experiences with us. By necessity, we have had to edit these interviews for flow and brevity, but this is absolutely

Next page