First published in 2015

Copyright David Wyn Williams 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Allen & Unwin

Level 3, 228 Queen Street

Auckland 1010, New Zealand

Phone: (64 9) 377 3800

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065, Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.co.nz

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the National Library of New Zealand

ISBN 978 1 877505 54 6

eISBN 978 1 925267 39 6

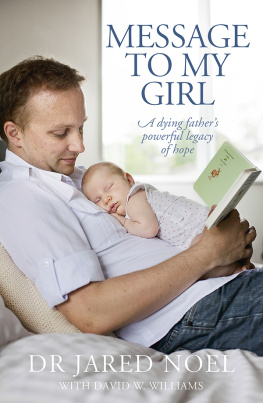

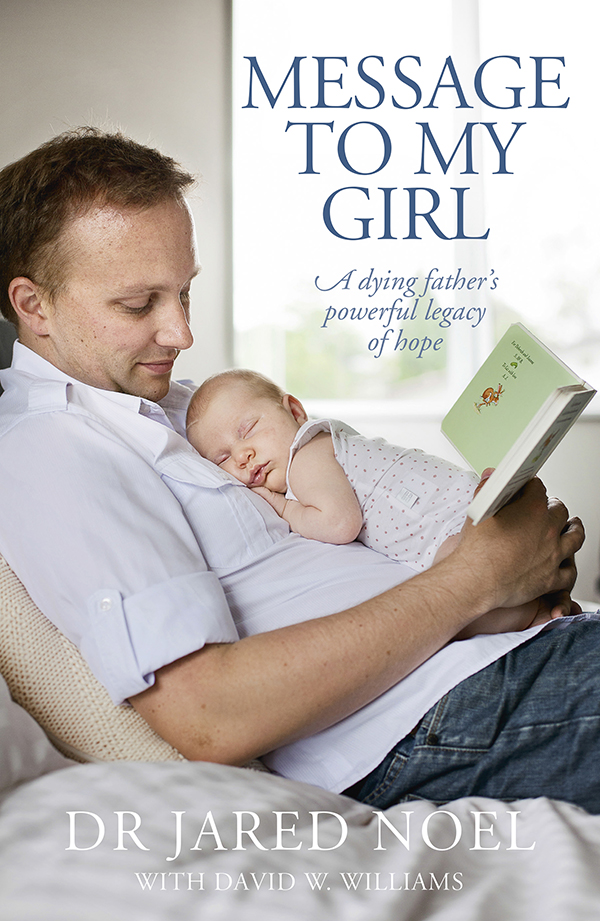

Cover images: Sam Mothersole/OHBaby!

Cover design: Kate Barraclough

Contents

I have a job that confronts life, death and everything in between.

I have a life that confronts living, dying and the reality of being in the middle.

I have patients who have to confront their own mortality in order to find their life.

Currently I work on the cardiothoracic ward at Auckland Hospital. We have people of all ages who have to go through what can only be described as major surgery, not without its risk, in order to squeeze more out of life. For some, they squeeze an extra five years; for others, the younger patients, they aim to squeeze another 50. Some are successful and, as I discovered in the first week of the job, some make great progress only to have their heart stop, and despite all efforts, not restart.

When life and death are so closely intertwined with day-today work, you can almost become desensitised to death. Death can become another statistic and then I remember my diagnosis. I remember that I am going to become that statistic. I remember that behind that statistic is a life. One lived (hopefully) well, and one that hopefully dies well.

Then I remember that we are all dying. Ten out of ten people will die, we just do it at different rates; we do it unpredictably. Whether it is being hit by a bus, or being diagnosed with cancer, or passing away in our sleep in the distant future, we are all heading in the same direction.

And then I realise that while I might be at risk of desensitisation to death and dying, what I have noticed is that others are desensitised to being alive. Somehow, the value of life has been forgotten because medicine has been so good at hiding us from death.

Life for me has become a precious commodity, one that carries more value than any comparative analogy might offer. I know my life is short, but it is worth every second, and every breath, because they are breaths and seconds that I will never get to relive. I have seen too many people who have become desensitised to life, those for whom money, Apple products, ambition or self-interest retain more value than the breath they just took. Apple products are cool, but the breath I just took is what allows me to appreciate them; and the breath I just took has no value but for the grace of God who gives it to me.

And if I value my own breath so much, then it is a waste if it is not spent serving those who also breathe otherwise Im a self-serving fool.

Life, death, and breathing, The Boredom Blog, June 22, 2011

At the funeral of Dr Jared Noel on Monday, October 13, 2014, his friend and colleague Dr Paul Sharplin told a story about what he called Jareds cancer bombs, one-liners Jared was fond of using about his cancer as a way of making conversation with friends unbearably awkward. He was the consummate conversation stopper, drawing on his black humour to help him cope with the fact that he was dying, while also acting on his conviction that those around him should approach his condition with the same level of humour, honesty and humanity as he did himself.

For almost six years, from his initial diagnosis through to his death, Jared used words to help him face his illness with grace and nobility. He also used words to educate people on how to live well in the face of their mortality, and how to confront taboo subjects such as cancer, dying, suffering, love, faith and doubtconversation stoppers Jared had a knack of turning into conversation starters. Soon after his diagnosis in November 2008, Jared began a blog that, by the time of his death, had attracted three-quarters of a million views. He began the blog initially to alleviate his boredom during rounds of chemotherapy, but it quickly became the means by which he kept friends and distant family members abreast of his condition. Ultimately, it became a didactic tool, challenging the taboos of death and dying with humour and unnerving honesty, and encouraging readers to recognise and treasure moments in life they would ordinarily take for granted. As Jareds readership grew, he wondered at the extraordinary turn his life had taken and the audience he had been given to share his thoughts with. This was a gift he never took for granted. His customary sign-off, Thanks for listening, was an authentic note of gratitude that gave Jared purpose until his very last days.

From one small post titled The birth of something new Jareds words became thoughts, his thoughts became blogs, the blogs became interviews, the interviews resulted in articles, the articles became conversations, and then, one day, the conversations ended. The ultimate taboo, death itself, brought an end to Jareds moment in the spotlight. But not before he impacted thousands of people with his inspirational message of living a full life in every moment while acknowledging and tackling head-on the brutal realities of that same life. In his final weeks, Jared became determined to record his reflections so the conversation could continue well after his own voice had ceased to play its part.

When I met Jared for the first time, on August 26, 2014, he was alone in a room in the West Auckland Hospice, sitting upright in bed and waiting for nothing in particular. Some weeks later, I discovered from his wife, Hannah, that this was a particularly difficult time for Jared, not just because he was preparing to die but because, in his words, he had nothing to do and nothing to say. His dream of putting his story together, primarily so that his baby daughter, Elise, might one day know her dad, was fading quickly. By his own estimate, he had no more than eight weeks to live.

I had known Jared for about eighteen months or so, but we had never met. I had seen him from time to time in my favourite caf, which was owned and operated by a collective of which he was a member. Like others, I had followed his growing media profile and read his blog. What I liked about Jareds posts was his ability to speak about taboo matters with disarming and confrontational honesty but also, because he was a doctor, with clinical precision and pragmatism. His was a refreshing and healing approach to a heavy topic that had become very personal to me in the preceding twelve months.

The magazine I published at the time ran a small story when friends of Jared began a Givealittle crowdfunding campaign to raise money for a course of chemo treatment that would keep him alive long enough to meet his then unborn child. It was a remarkable campaign, and Jareds story had a great impact on the New Zealand public. The picture of Jared I had in my head when I fronted up to the hospice that day was the smiling, youthful face that had been published on the front page of the national newspaper, The New Zealand Herald.