To Robert W. Funk and my fellow members of

the Westar Institutes Jesus Seminar

for their courage, collegiality, and consistency .

Rome, Museo Nazionale delle Terme. (Alinari/Art Resource, NY.)

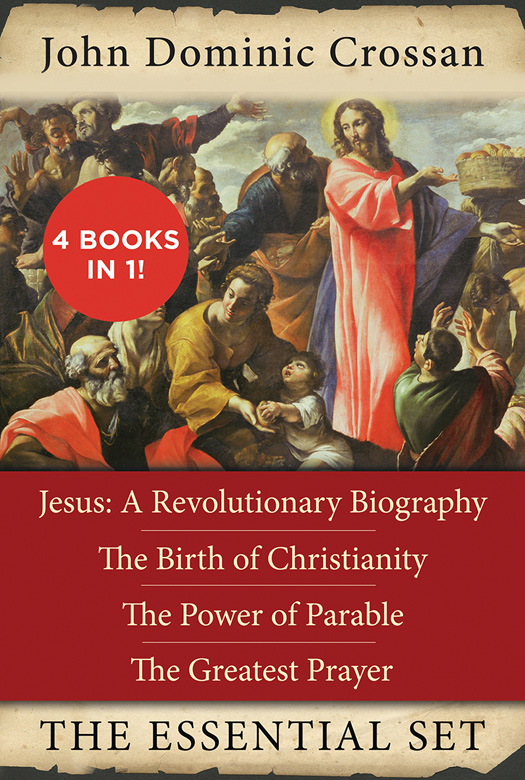

The above relief is not so much decoration as summary of this book. The relief is one of two twin-registered polychrome marble plaques containing biblical scenes and dating to the first years of the fourth century C.E.

Twin scenes of free healing frame a central image of open eating, which are, as this book maintains, the heart of Jesus original vision and program. At left Jesus heals the paralytic who carries off his bed, as in Mark 2:112. And at right the widows son at Nain arises from his bier, as in Luke 7:1116. Jesus faces inward at the plaques half-broken left side; he presumably looked inward at the right, which is totally broken. In the lower center are four figures in typical pose for a pagan meal with the dead. The middle two are reclining behind a barely visible curved bolster while the outer pair seem to be serving them. They have six basketsthat is, lots of foodand are both eating and drinking (note goblet in right hand of third from left). That classical scene in the lower center is subsumed into a multiplication of the loaves (but no sign of fishes), as in Mark 6:3544 or John 6:513, by its conjunction with the upper center scene where three disciples, at left, lead toward Jesus, at right. Finally, Jesus himself is designated as a teacher or philosopher by the scroll in his hand. In both cases he wears the pallium of Greek wisdom rather than the toga of Roman power. But, while in the scene to the left he wears both outer pallium and inner tunic, in the center he wears the pallium without the tunic, leaving his right shoulder and body bare. He is portrayed as not just any type of philosopher but, precisely, a Cynic philosopher.

We find Jesus healing, eating, teaching, and more like a Cynic philosopher than anything elsein other words, this book in iconographic miniature.

T RYING TO FIND THE ACTUAL J ESUS is like trying, in atomic physics, to locate a submicroscopic particle and determine its charge. The particle cannot be seen directly, but on a photographic plate we see the lines left by the trajectories of larger particles it put in motion. By tracing these trajectories back to their common origin, and by calculating the force necessary to make the particles move as they did, we can locate and describe the invisible cause. Admittedly, history is more complex than physics; the lines connecting the original figure to the developed legends cannot be traced with mathematical accuracy; the intervention of unknown factors has to be allowed for. Consequently, results can never claim more than probability; but probability, as Bishop Butler said, is the very guide of life.

Morton Smith, Jesus the Magician

(San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1982)

This book gives my own reconstruction of the historical Jesus derived from twenty-five years of scholarly research on what actually happened in Galilee and Jerusalem during the early first century of the common era. But why should any such research be necessary at all? Have we not, for Jesus, this first-century Mediterranean Jewish peasant, four biographies, by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Johnindividuals all directly or indirectly connected with him, and all writing within, say, seventy-five years of his death? Is that not equal to or even better than the research on the contemporary Roman emperor, Tiberius, for whom we have biographies by Velleius Paterculus, Tacitus, Suetonius, and Dio Cassius, only the first of whom was directly connected with him, the others writing from seventy-five to two hundred years after his death? Why, then, with such abundant documentation, is there a need for any scholarly search for the historical Jesus?

It is precisely that fourfold record that constitutes the core problem. If you read the four gospels vertically and consecutively, from start to finish and one after another, you get a generally persuasive impression of unity, harmony, and agreement. But if you read them horizontally and comparatively, focusing on this or that unit and comparing it across two, three, or four versions, it is disagreement rather than agreement that strikes you most forcibly. And those divergences stem not from the random vagaries of memory and recall but from the coherent and consistent theologies of the individual texts. The gospels are, in other words, interpretations. Hence, of course, despite there being only one Jesus, there can be more than one gospel, more than one interpretation.

That core problem is compounded by another one. Those four gospels do not represent all the early gospels available, or even a random sample within them, but are instead a calculated collection known as the canonical gospels. This becomes clear in studying other gospels either discerned as sources inside the official four or else discovered as documents outside them.

An example of a source hidden inside the four canonical gospels is the reconstructed document known as Q , from the German word Quelle , meaning source, which is now imbedded within both Luke and Matthew. Those two authors also use Mark as a regular source, so Q is discernible wherever they agree with one another but lack a Markan parallel. Since, like Mark, that document has its own generic integrity and theological consistency apart from its use as a Quelle or source for others, I refer to it in this book as the Q Gospel .

An example of a document discovered outside the four canonical gospels is the Gospel of Thomas , which was found at Nag Hammadi, in Upper Egypt, in the winter of 1945 and is, in the view of many scholars, completely independent of the canonical gospelsMatthew, Mark, Luke, and John. It is also most strikingly different from them, especially in its format, and is, in fact, much closer to that of the Q Gospel than to any of the canonical foursome. It identifies itself, at the end, as a gospel, but it is in fact a collection of the sayings of Jesus given without any compositional order and lacking descriptions of deeds or miracles, crucifixion or resurrection stories, and especially any overall narratival or biographical framework. The existence of such other gospels means that the canonical foursome is a spectrum of approved interpretation forming a strong central vision that was later able to render apocryphal, hidden, or censored any other gospels too far off its right or left wing.

Suppose that in such a situation you wanted to know not just what early believers wrote about Jesus but what you would have seen and heard if you had been a more or less neutral observer in the early decades of the first century. Clearly, some people ignored him, some worshiped him, and others crucified him. But what if you wanted to move behind the screen of credal interpretation and, without in any way denying or negating the validity of faith, give an accurate but impartial account of the historical Jesus as distinct from the confessional Christ? That is what the academic or scholarly study of the historical Jesus is about, at least when it is not a disguise for doing theology and calling it history, doing autobiography and calling it biography, doing Christian apologetics and calling it academic scholarship. Put another way, no matter how fascinating result and conclusion may be, they are only as good as the theory and method on which they are based.