Table of Contents

Guide

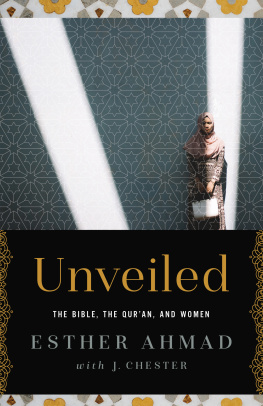

HARVEST HOUSE PUBLISHERS

EUGENE , OREGON

Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV. Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Verses marked NKJV are taken from the New King James Version. Copyright 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Cover design by Studio Gearbox

Interior design by KUHN Design Group

Cover photo Izzaidi Kosno/EyeEm / Gettyimages; Rowena Naylor / Stocksy; New Line, Anna Pogliaeva / Shutterstock

Published in association with Jenni Burke of Illuminate Literary Agency: www.illuminateliterary.com

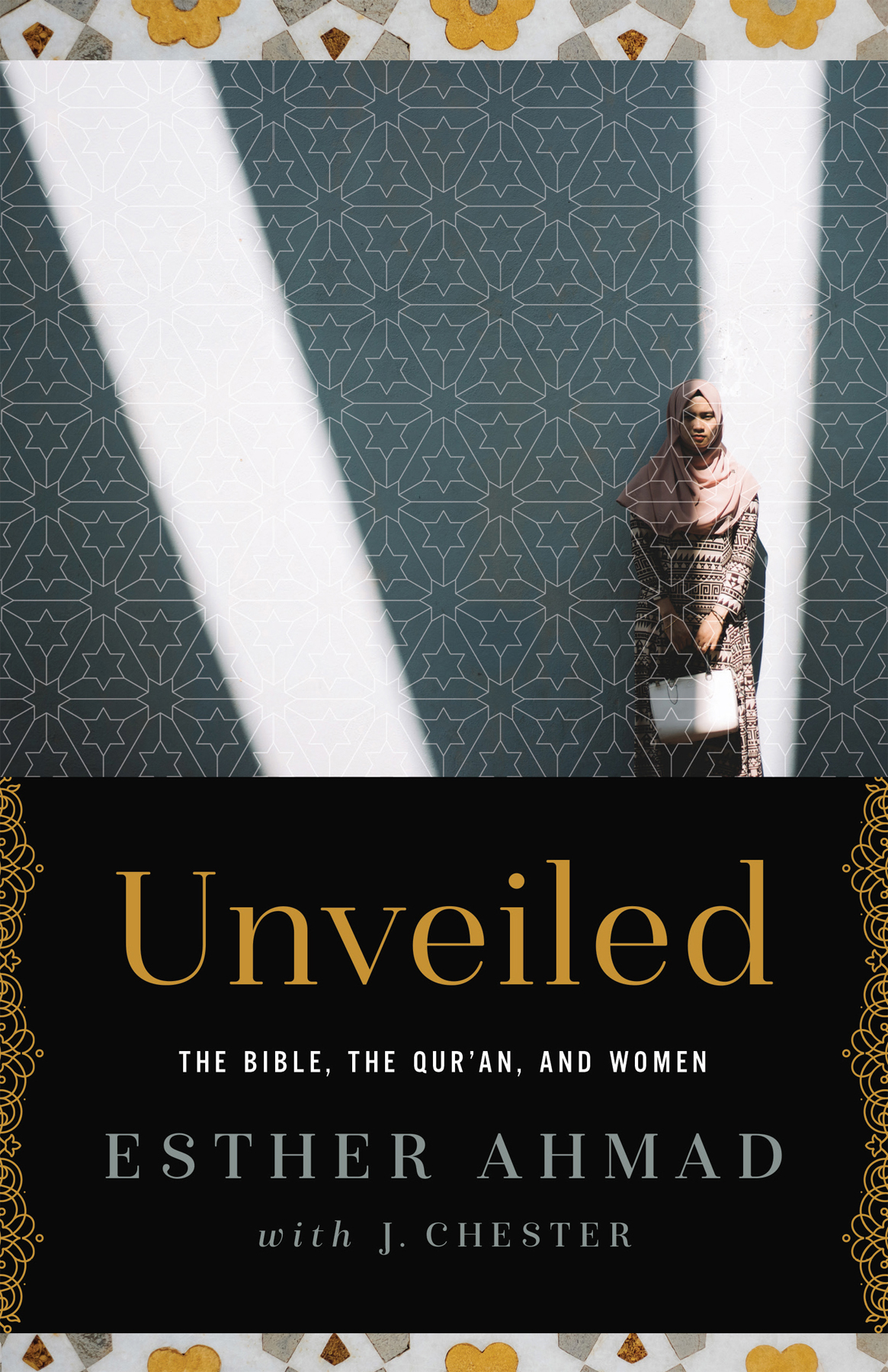

Unveiled

Copyright 2020 by Esther Ahmad

Published by Harvest House Publishers

Eugene, Oregon 97408

www.harvesthousepublishers.com

ISBN 978-0-7369-7230-7 (pbk)

ISBN 978-0-7369-7231-4 (eBook)

Library of Congress Control Number 2019920940

All rights reserved. No part of this electronic publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, digital, photocopy, recording, or any otherwithout the prior written permission of the publisher. The authorized purchaser has been granted a nontransferable, nonexclusive, and noncommercial right to access and view this electronic publication, and purchaser agrees to do so only in accordance with the terms of use under which it was purchased or transmitted. Participation in or encouragement of piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of authors and publishers rights is strictly prohibited.

For John and Amiyah

Contents

I suppose you could say that this all started with a search. It was not a physical search, you understandI did not even have to leave the house. My daughter, Amiyah, was at school, my husband, John, was studying opposite me at the kitchen table, and I had completed my chores for the morning. All I had to do was open the laptop, make my way to the Facebook search bar, and type.

Why was I doing this? It was a feeling, a vague notion that had been on my mind for days. Like a compass needle swinging north, my thoughts had returned to it constantly. When I was sleeping, when I was reading my Bible, when I was reading Amiyahs bedtime story or talking with John about his day, the same idea returned again and again: there was someone out there to whom I needed to talk in Urdu, the language of my birth. Someone I needed to find and start a conversation with about what it means to follow Jesus.

So after praying about it, talking with John, and then praying some more for almost another week, I was finally ready. Even though I had no idea where the search would take me, I knew exactly what I was looking for: someone who would identify themselves by two simple wordsPakistani and Muslim.

For my first eighteen years, I was also defined by those two words. I know they are powerful enough to direct every single aspect of your life, from what you wear and what you eat to everything about your work and marriage. And I know how these words can even dictate the manner of your death.

But what I did not know, as I stared at the endless page of results, was what I was supposed to do next.

Him, said John from behind me, taking a sip of his chai as he pointed to one of the first results. You should click on him. He looks Johns voice trailed off. It was hard to say what the man in the picture looked like. In some ways, he looked like a typical conservative Muslim from my homeland, with his long beard and beige shalwar kameez , a traditional garment common in Pakistan. But he was holding the hand of a little girl, who I guessed was his daughter. His smile was almost as big as hers. It was unusual to see a man identify as the father of a girl like that.

Different? I said.

Lost.

I sent a friend request with a simple greeting. He was online and replied within minutes.

I dont know you. Who are you?

My name is Esther. I am living in the US.

Yes, I can see this. Why are you messaging me?

It was a good question. He deserved an honest answer. I used to live in Pakistan. I like the picture of you holding your daughters hand; it reminds me of my childhood. He went silent after that. I checked my watch. It was after midnight in Pakistan. Had I found the right person? I had no idea.

There was a message waiting for me the next day: I have a question I would like you to answer. Esther is a Christian name and Ahmad is Muslim. Why do you have two different types of name?

Another good question, but this time the truth would be a little more complicated to explain. I decided to tell him what I could of my story without scaring him off. One of my parents converted, but they both liked both the names. I paused before hitting send and added a final line: I am a Christian. That was one bit of my story I had no intention of skipping over. If it ended our conversation, so be it.

It did not. He came straight back to me.

Do you know about Islam?

Oh, Ive had some experience, but Id like to ask you some questions about it. And maybe if you have any questions for me about Christianity, you could ask me.

I was not surprised that he ignored my offer, but he started telling me about his life. His name was Mustafa, he was thirty-seven, and he was from a city in Pakistan Id visited a few times. He was married with four childrentwo girls and two boysbut he was not living with his family. Mustafa explained that he was actually living in Qatar, working with some friends on a start-up.

It must be hard to be separated from your wife and children like that, I wrote. Your kids are cute, by the way. But tell me, Mustafa, why didnt you put a picture of your wife up?

Most people I know dont allow their wives to be on Facebook. And if ever they do, they dont let them share their own pictures. We are very strict about this. We would only ever let them put up pictures of their husband, other family, or places. Never of themselves.

Nothing about his words surprised me, but his response reminded me so much of what it meant to be a Muslim woman in Pakistan. Back when I was growing up, there had been no Facebook or sharing of photos online, but the rules were just as strict. Almost every decision I ever faced was made for me by my father, and for almost two decades, I was a slave in so many senses of the word.

That is why, whenever I got to the end of one of Mustafas messages, I started to believe that he was precisely the person with whom God had planned for me to talk. Beneath his name, he would always write the words slave of Muhammad.

Look, J, I said, pointing it out to John. I dont know that hes lost. But I do know that hes trapped. Maybe Gods going to set him free.

Over the next few days, Mustafa and I carried on trading messages with each other. I told him a bit about my family, about John and Amiyah, and about how in 2016 we had been granted asylum by the United States. I did not explain where we had been living before or why we had been forced to leave in the first place, and Mustafa did not ask. I was glad about that. I wanted to tell him my full story one day, but not yet.

Next page