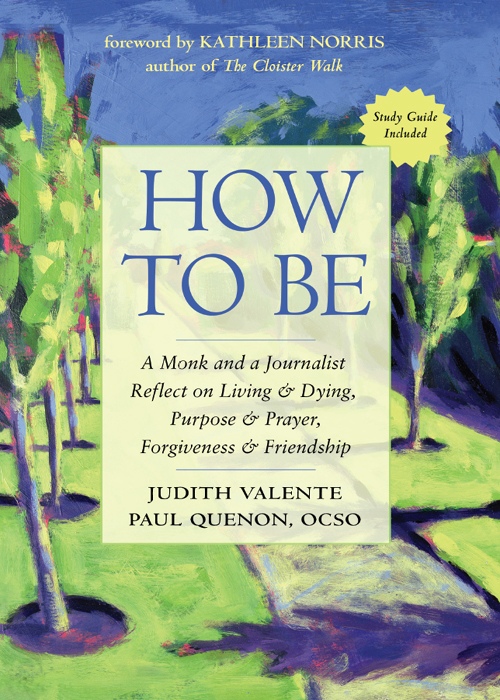

PRAISE FOR

HOW TO BE

______________________

Snow fell outside my dark study as I read these exquisitely simple letters by computer light. I was a blissed-out fly on their writing desks as I buzzed back and forth between these wise words exchanged between a married woman and a monk. In the end, I was overjoyed for having spent hours in their good company. Their friendship saturated me with comfort and calm. So many good words made me happy, especially I know you and you know me. But wait. I hardly know myselfat least not, as yet, in the totality of what I will be. The little letters we write, the casual contacts we make in life, the fragments of acquaintance, the relationships, broken or made whole, are just the beginning. Each is a small seed of what can develop in eternity. None of it is ever lost. Nothing is ever lost. Oh, thank you both for including me.

JON MONTALDO, editor of The Intimate

Merton (with Brother Patrick Hart)

These letters remind us that the monastic life is a gift to the world. The prayers and teachings of monks and nuns are here to help make contemplatives of all of us, regardless of where we live.

JON M. SWEENEY, coauthor of Meister Eckhart's Book of

the Heart; translator of Francis of Assisi in His Own Words

This small book brought me joy and solace at a difficult timewhat more may I say? Such a pleasure to read the correspondence of two thoughtful, perceptive people about what really matters. This small book demonstrates again that letters are among our most important literary forms.

FENTON JOHNSON, author of At the Center of All Beauty

This book is a small taste of eternity as Judith and Br. Paul invite us into stories of ancient wisdom lived in contemporary contexts. Modeled through letter writing and spiritual friendship, they tackle some of the biggest questions: change and stability, humility and purpose, time and eternity, life and the afterlife. This book preserves ageless monastic wisdom as monasticism itself is evolving before our eyes. People of all spiritual backgrounds and across generations will find insight on how to live through challenging times, personally and societally, in these pages.

KATIE GORDON, cofounder of Nuns and Nones

and staff member of Monasteries of the Heart

Copyright 2021

by Judith Valente and Paul Quenon

Foreword copyright 2021 by Kathleen Norris

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC. Reviewers may quote brief passages.

Cover design by Kathryn Sky-Peck

Cover photograph Avenue Sara Hayward/Bridgeman Images

Interior by Maureen Forys, Happenstance Type-O-Rama

Typeset in Sabon and Centaur

Hampton Roads Publishing Company, Inc.

Charlottesville, VA 22906

Distributed by Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC

Sign up for our newsletter and special offers by going to www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter.

ISBN: 978-1-64297-034-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

Printed in the United States of America

IBI

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

www.redwheelweiser.com

For my husband,

Charles Reynard,

and for the monks of

the Abbey of Gethsemani

past, present, and future.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

______________________________

FOREWORD

______________________________

T his book of correspondence is a refreshment, a reminder that although interconnectivity has become a buzzword, and technology allows us to contact one another in a dazzling variety of new ways, something vital is missing. Emails travel around the world in seconds, but in gaining efficiency and speed, we risk losing the ability to listen. We long for deeper communion with others, and this book shows us one way to find it.

How to Be introduces us to Judith Valente, a married woman, a journalist and retreat leader with a hectic schedule, and Brother Paul Quenon, a celibate and a contemplative Cistercian monk of the Abbey of Gethsemani. We all benefit from the decision they made to deepen their relationship by means of letters. Br. Paul's helpful comment about the difference between an email message and correspondence is borne out in etymology. The word message is related to mission and implies using words to advance an agenda. The word correspondence, by comparison, is derived from engagement, suggesting something deeper, a pledge to be open and honest with another person. In corresponding with a friend, we have no agenda other than fostering friendship.

That's inspiring, but the reader might wonder about the value of paying attention to the ramblings of two people, as interesting as they are. Reading their letters could seem as meaningless as hearing another person's dreams. But the subjects these two touch on are universal. We all deal with illness and death, grief and loss, work, play, and the use of our time, and the musings in these letters can help us determine our own path through the glorious mess called life.

Like Judith, most of us know what it's like to be so consumed by work that we lose sleep over it. We fret over being so overloaded and distracted that at the end of the day we feel it's all been wasted time. But few of us hear the wisdom of Br. Paul's response to her lament: that a good way to get over the feeling that you're wasting your time is to waste more of it. He suggests that she intentionally slow down and look around her to see what's really there. How liberating to embrace his Zen-like wisdom, that the purpose of life is that it doesn't need a purpose: the purpose of life is life.

It's good to hear two thoughtful people reflecting on their lived experience. Judith, a self-described over-achiever, is often anxious and Paul is more calm, reflecting on the fruits of a monastic life structured so as to foster contemplation. Both are modern people, well aware of the uneasiness that pervades our culture. But Paul reminds is that it's all right to admit that we don't always know what to hope for. If we don't understand what's happening to and around us, maybe that's how God wants it. Citing a comment by his mentor Thomas Merton that Jesus will always seek out the most lowly crib, he adds that the holy is often found in the places we are most reluctant to look.

Many of us can identify with Judith's difficulty in devoting time to pray, let alone praying attentively, and with Br. Paul's admission that he tends to fall asleep when he's meditating. Fortunately their views on spirituality and religion are not sectarian, and both reflect on experiences with people of other faiths. Paul offers an indelible image of Buddhist monks playing soccer with children outside Merton's hermitage; Judith discusses her study of meditation with a Tibetan Lama. As Christians, both ponder their experience of receiving the eucharist at Mass. Judith speaks of the wonder of carrying the body of Christ within her; Paul says it makes him realize that every Christian is a reincarnation of Christ.

One thing that connects these two disparate people is poetry, and it's delightful to see the way they share their own poems as well as the work of others who have inspired them: Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and a contemporary, Mary Oliver. Poets do not shy away from difficult subjects, and the reflections on suffering and death in these letters have been especially helpful to me. Judith recalls that a man she'd interviewed for a

Next page