FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION , November 1988

Copyright 1987 by Laura Palmer

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published, in hardcover, by Random House, Inc., in 1987 .

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Charlie King: Excerpt from the lyrics to Trying to Find a Way Home by Charlie King. Copyright 1983 Charlie King/Pied ASP Music (BMI), 158 Cliff Street, Norwich, CT 06360.  1984 Flying Fish Recording, MY HEART KEEPS SNEAKIN UP ON MY HEAD, FF .

1984 Flying Fish Recording, MY HEART KEEPS SNEAKIN UP ON MY HEAD, FF .

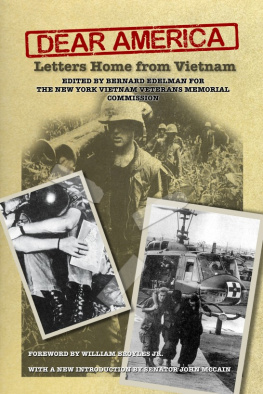

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc: The excerpt from a letter from Phil Woodall to his father, from Dear America: Letters Home from Vietnam, edited by Bernard Edelman for the New York Vietnam Veterans Memorial Commission, is reprinted by permission of Phil Woodall and the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. Copyright 1985 by the New York Vietnam Veterans Memorial Commission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Palmer, Laura.

Shrapnel in the heart.

1. Vietnam Veterans Memorial (Washington, D.C.)

2. American letters. 3. Vietnamese Conflict, 19611975 Biography.

4. Washington (D.C.)Buildings, structures, etc. I. Title.

D S559.83. W18P35 1988 959 70438 8817375

eISBN: 978-0-307-76563-5

v3.1

This book is dedicated to those

who never made it home from Vietnam,

both the living and the dead,

and to the people who love them

so very, very much

Few had forebodings of their destiny. At the halts they lay in the long wet grass and gossiped, enormously at ease. The whistle blew. They jumped for their equipment. The little gray figure of the colonel far ahead waved its stick. Hump your pack and get a move on. The next hour, man, will bring you three miles nearer to your death. Your life and your death are nothing to these fieldsnothing, no more than it is to the man planning the next attack at G.H.Q. You are not even a pawn. Your death will not prevent future wars, will not make the world safe for your children. Your death means no more than if you had died in your bed, full of years and respectability, having begotten a tribe of young. Yet by your courage in tribulation, by your cheerfulness before the dirty devices of this world, you have won the love of those who have watched you. All we remember is your living face, and that we loved you for being of our clay and our spirit.

G UY C HAPMAN , A Passionate Prodigality

Magnicourt-sur-Canche, France

21 October 1916

For we do not want you to be ignorant, brethren, of the affliction we experienced in Asia; for we were so utterly, unbearably crushed that we despaired of life itself. Why, we felt that we had received the sentence of death; but that was to make us rely not on ourselves but on God who raises the dead; he delivered us from so deadly a peril, and he will deliver us; on him we have set our hope that he will deliver us again. You also must help us by prayer, so that many will give thanks on our behalf

2 C ORINTHIANS 1: 811

Contents

Introduction

They were ours.

In the simplicity of those three words is the power of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and the purpose of this book. The memorial asks that you remember; here are their names. Shrapnel in the Heart lets you listen; here are their stories, told by the people who loved them.

We have heard about Vietnam from the generals and journalists, soldiers and spies, politicians and historians. Now it is the turn of the people who lost the most and have said the least: the mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, children, friends, wives, sweethearts, and buddies of the men who died in Vietnam. They tell tenderly, painfully, and sometimes angrily about what it means to lose someone you love in a war that much of the country came to hate. But this is not a book about despair. This is a book about love, love that bombs cant shatter and bullets cant kill.

Shrapnel in the Heart is a collection of letters and poems that have been left at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. In the five years of its existence, the memorial, unexpectedly, became a place not only to honor but to communicate with the dead. The messages that have been left there speak eloquently of loss and remembrance:

I have dreamed of the day youll come home and finally be my Dad. You would have been the best Daddy in the whole world.

Im the one who rocked him as a baby.

My prayer, my dear and sweet husband, is that the world would forever know peace.

Hi Lover! Seventeen years youre still twenty-oneforever young, but gone. Murdered. And nothing will make your loss to us less of a tragedy.

Material like this does not exist at any other American monument. Never before, it seems, have people unburdened themselves on paper and left their intimate thoughts at a public memorial.

When I went to the memorial for the first time, on New Years Day, 1986, I had no inkling this book was in the offing. I went alone and spent six hours at the wall, mesmerized and moved. The names seemed to go on forever; it felt eternally sad.

Vietnam has been a large part of my life. I grew up in the sixties and worked in Saigon as a reporter in the early seventies. But oddly, when I made that initial visit to the memorial, none of that seemed to matter. I was moved simply as a mother. Name one child, your own, and each of the 58,132 names on the wall will break your heart.

I was fascinated by what was happening at the memorial: one by one, without anyone suggesting it, people were silently crossing over their moat of grief and leaving a letter, poem, or other offering at the wall. It seemed almost un-American; we are so proud, so noisy, so extroverted. Yet here, in a sacred and silent ritual, a side of ourselves that we are reluctant to show was being revealed.

This rite of remembrance began with the plunk of a Purple Heart into wet cement. As the foundation of the memorial was being poured, a man asked construction workers if he could drop his brothers medal into the concrete. He saluted as it slid beneath the surface. There have been more than six thousand similar salutes since the memorial was officially dedicated on Veterans Day, November 11, 1982.

It was then that America finally turned to embrace her own. Engraved on the walls black granite panels that pry open the earth are the names of every man and woman who went to Vietnam and never came back. In dedicating the memorial, America finally acknowledged that we lost more than the war in Vietnam; we lost the warriors. The war was deplorable, not the men who served. But that distinctionthat the outcome of the war was not the fault of the men who fought ithad never been adequately made before. It had been nearly a decade since the fall of Saigon, but the most powerful nation in the world was finally able to say, They were ours, and begin a long-overdue period of national mourning.

Since then, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial has become the place where America is coming to terms with the Vietnam War.

1984 Flying Fish Recording, MY HEART KEEPS SNEAKIN UP ON MY HEAD, FF .

1984 Flying Fish Recording, MY HEART KEEPS SNEAKIN UP ON MY HEAD, FF .