Table of Contents

ALSO BY WENDY DONIGER

Siva, the Erotic Ascetic

The Origins of Evil in Hindu Mythology

Dreams, Illusion, and Other Realities

Splitting the Difference: Gender and Myth in Ancient Greece and India

TRANSLATIONS:

The Rig Veda

The Laws of Manu

and

Kamasutra

KATHERINE ULRICHstudent, friend, editor supreme

and

WILL DALRYMPLEinspiration and comrade in the good fight

INDIAS MAJOR GEOGRAPHICAL FEATURES

INDIA FROM 2500 BCE TO 600 CE

INDIA FROM 600 CE TO 1600 CE

INDIA FROM 1600 CE TO THE PRESENT

PREFACE:

THE MAN OR THE RABBIT

IN THE MOON

AN ALTERNATIVE HISTORY

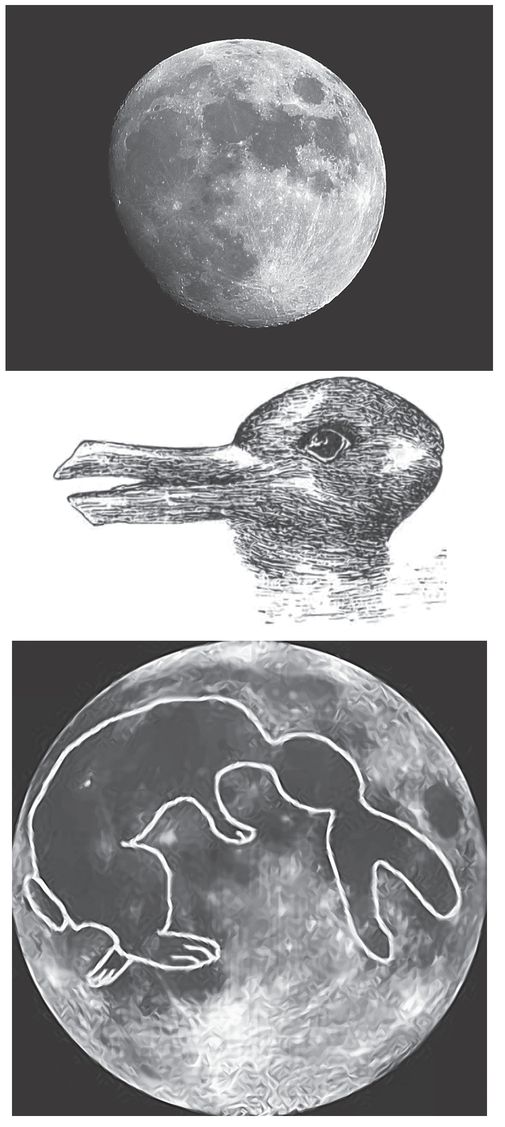

The image of the man in the moon who is also a rabbit in the moon, or the duck who is also a rabbit, will serve as a metaphor for the double visions of the Hindus that this book will strive to present.

Since there are so many books about Hinduism, the author of yet another one has a duty to answer the potential readers Passover question: Why shouldnt I pass over this book, or, Why is this book different from all other books? This book is not a brief survey (you noticed that already; I had intended it to be, but it got the bit between its teeth and ran away from me), nor, on the other hand, is it a reference book that covers all the facts and dates about Hinduism or a book about Hinduism as it is lived today. Several books of each of those sorts exist, some of them quite good, which you might read alongside this one. The Hindus: An Alternative History differs from those books in several ways.

[TOP] The Mark on the Moon, [MIDDLE] Wittgensteins Duck/ Rabbit, and [BOTTOM] The Rabbit in the Moon

First, it highlights a narrative alternative to the one constituted by the most famous texts in Sanskrit (the literary language of ancient India) and represented in most surveys in English. It tells a story that incorporates the narratives of and about alternative peoplepeople who, from the standpoint of most high-caste Hindu males, are alternative in the sense of otherness, people of other religions, or cultures, or castes, or species (animals), or gender (women). Part of my agenda in writing an alternative history is to show how much the groups that conventional wisdom says were oppressed and silenced and played no part in the development of the traditionwomen, Pariahs (oppressed castes, sometimes called Untouchables)did actually contribute to Hinduism. My hope is not to reverse or misrepresent the hierarchies, which remain stubbornly hierarchical, or to deny that Sanskrit texts were almost always subject to a final filter in the hands of the male Brahmins (the highest of the four social classes, the class from which priests were drawn) who usually composed and preserved them. But I hope to bring in more actors, and more stories, upon the stage, to show the presence of brilliant and creative thinkers entirely off the track beaten by Brahmin Sanskritists and of diverse voices that slipped through the filter, and, indeed, to show that the filter itself was quite diverse, for there were many different sorts of Brahmins; some whispered into the ears of kings, but others were dirt poor and begged for their food every day.

Moreover, the privileged male who recorded the text always had access to oral texts as well as to the Sanskrit that was his professional language. Most people who knew Sanskrit must have been bilingual; the etymology of Sanskrit (perfected, artificial) is based upon an implicit comparison with Prakrit (primordial, natural), the language actually spoken. This gives me a double agenda: first to point out the places where the Sanskrit sources themselves include vernacular, female, and lower-class voices and then to include, wherever possible, non-Sanskrit sources. The (Sanskrit) medium is not always the message; its not all about Brahmins, Sanskrit, the Gita. I will concentrate on those moments within the tradition that resist forces that would standardize or establish a canon, moments that forged bridges between factions, the times of the mixing of classes (varna-samkara) that the Brahmins always triedinevitably in vainto prevent.

Second, in addition to focusing on a special group of actors, I have concentrated on a few important actions, several of which are also important to us today: nonviolence toward humans (particularly religious tolerance) and toward animals (particularly vegetarianism and objections to animal sacrifice) and the tensions between the householder life and renunciation, and between addiction and the control of sensuality. More specific images too (such as the transposition of heads onto bodies or the flooding of cities) thread their way through the entire historical fabric of the book. I have traced these themes through the chapters and across the centuries to provide some continuity in the midst of all the flux, even at the expense of what some might regard as more basic matters.

Third, this book attempts to set the narrative of religion within the narrative of history, as a linga (an emblem of the god Shiva, often representing his erect phallus) is set in a yoni (the symbol of Shivas consort, or the female sexual organ), or any statue of a Hindu god in its base or plinth (pitha). I have organized the topics historically in order to show not only how each idea is a reaction to ideas that came before (as any good old-fashioned philological approach would do) but also, wherever possible, how those ideas were inspired or configured by the events of the times, how Hinduism, always context sensitive, This book attempts to extend that particularizing project to the whole sweep of Indian history, from the beginning (and I do mean the beginning, c. 50,000,000 BCE) to the present. This allows us to see how certain ongoing ideas evolve, which is harder to do with a focus on a particular event or text at a particular moment.

This will not serve as a conventional history (my training is as a philologist, not a historian) but as a book about the evolution of several important themes in the lives of Hindus caught up in the flow of historical change. It tells the story of the Hindus primarily through a string of narratives. The word for history in Sanskrit, itihasa, could be translated as Thats what happened, giving the impression of an only slightly more modest equivalent of von Rankes phrase for positivist history: