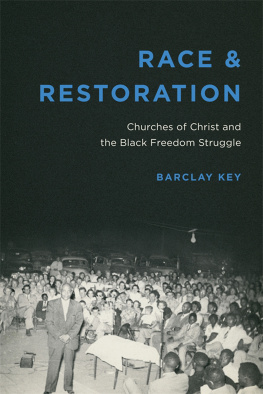

R ace matters. Even within a religious body that at times has claimed virtual immunityfrom the pressures of its social and historical context, the ever present and powerful confrontation between white and black has greatly affectedthe formation of Churches of Christ identity. Without a convention to make officialpronouncements on race relations or a conference to declare the formation of twodenominations along the Mason-Dixon Line some may believe Churches of Christ haveescaped the grasp of perhaps the most volatile issue in American history.

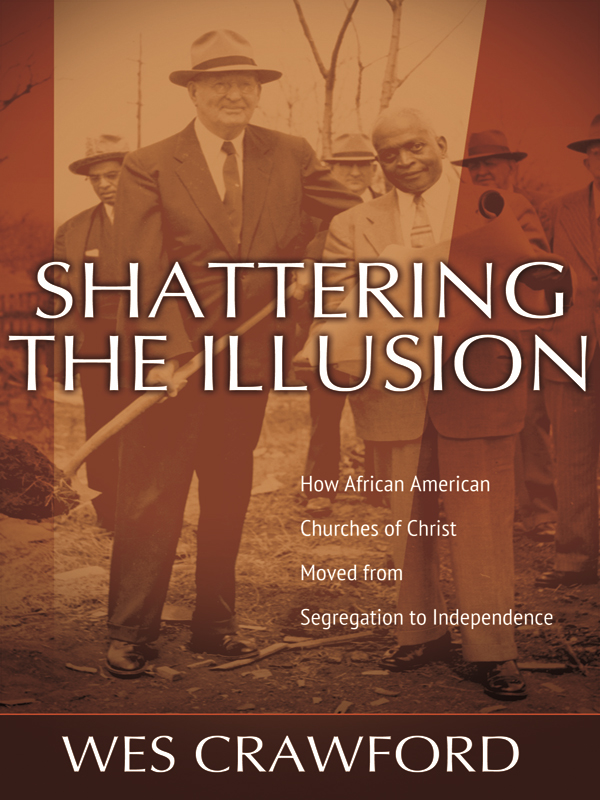

A history of segregation within the Churches of Christ has obscured their evolutionin the late twentieth century towards de facto denominational independence of theirAfrican American congregations. Predictably, much of that independence can be tracedto the cultural and political effects of the Civil Rights Movement at mid century.This book seeks to recover that history. In addition, it seeks to prove that Churchesof Christ journals, colleges, and lectureships shielded from view the full measureof the separation between African American and white members of the denomination.

This study contributes to the study of American church history in two ways. First,it challenges the illusion of racial unity among those congregations associated withChurches of Christ. African American and white members of this predominantly southernbranch of the Stone-Campbell Movement mirrored the white-imposed segregation of theirregional peers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; and, followingthe American Civil Rights Movement, the denomination remained divided as AfricanAmericans formally declared their independence from white paternalism and control.Second, this study reveals the power of unofficial denominational bodies to masksignificant division existent within its ranks. Lacking centralized authority, Churchesof Christ sought to mediate their theology through journals, colleges, and lectureships.As the only centralized voices of the denomination, these entities failed to addressthe division between African Americans and whites, thereby providing a false veneerof cohesion to insiders and outsiders alike. These three bodies not only failedto cohere African Americans and whites, they also helped maintain the illusion ofracial unity within Churches of Christ.

To set the stage for this study, one must become familiar with two key terms: raceand racism. Race is a socially constructed phenomenon; therefore, one is incorrectto speak of the white race or the African American race as if lighter skinnedindividuals are necessarily and by nature classified separately from darker skinnedindividuals. In 1887, a Presbyterian leader made the statement, The distinctionsof race are drawn by God Himself. For example, a person with a large nose or red hair doesnot automatically have to fight the stereotypes of mental inferiority or financialhardship. A person born with black skin, however, often has to fight both.

Those members of society who have exercised their hegemonic power have attached significantmeaning to white and black skin color. In his discussion of scientific racism,Brad Braxton reminds his readers that countless white scientists, in their effortsto support the myth of white intellectual superiority, have attempted to prove thatthe skulls of white persons were larger than the skulls of black persons. Thesequasi-scientific efforts, however, followed centuries wherein society attached positiveconnotations to white and negative connotations to black.

Some scholars have suggested that white racism toward African Americans began onanother continent, arguing that even before American colonization began, the Englishhad certain views of white and black. Of that time and place, wrote Winthrop Jordan,white and black connoted purity and filthiness, virtue and baseness, beauty andugliness, beneficence and evil, God and the devil.

Upon this discovery, English explorers, scientists, and clerics offered explanationsfor the black complexion. Although some borrowed more ancient and fanciful explanationslike the Phaeton myth, which implied that Ethiopians inherited their black skin fromPhaeton, a lad who drove his chariot too close to the sun, others proponents ofnaturalistic explanations postulated that darker skin somehow originated from thestronger heat of the African sun.

As Europeans encountered Africans, they not only found biblical justification fordark skin and slavery, they also attached new meaning to blackness. Black Africansbecame the picture of savagery to white Europeans, and their treatment of Africanslaves bore witness to this fact.

Other scholars such as Oscar and Mary Handlin have argued that whites attached negativeconnotations to blackness much later. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,English colonists, argued the Handlins, sought to justify the emerging institutionby referring to the Africans as barbarians and finding biblical justification forblack inferiority. In doing so, English colonists separated black slaves from otherslaves, including whites.

Whether white racism preceded American slavery or vice versa, the end result remainedconstant: in America, black skin had meaning.

The picture of black Africans painted by sixteenth-century explorers and scholarsas cursed, sexual savages ordained by God to servitude influenced generations ofEuro-Americans. By the eighteenth century, as scientists set out to classify planets,diseases, and animals, men like Francois Bernier and Carolus Linnaeus took on thetask of classifying humans as an integral part of the animal world; and the centralphysical feature they used to differentiate one human from the next was skin color.The next logical step was to rank humans from their lowest orders to their highest.Viewed as cursed, sexual savages, black-skinned humans were customarily viewed towardthe bottom of the Great Chain of Being, while whites were consistently near the top.

By the time of Americas revolution, the idea of black inferiority was firmly embeddedin the white, Western psyche. Even those whites who looked down upon slavery stillheld to the idea of black inferiority. Thomas Jefferson wrote, in reason they [blacks]are much inferior, as I think one could scarcely be found capable of tracing andcomprehending the investigations of Euclid; and that in imagination they are dull,tasteless, and anomalous.

From the pen of an American founder, one realizes, blackness had meaning. The portraitof blacks developed over centuries by scholars and politicians struck fear intothe minds and hearts of Americans. In the antebellum period, white Americans fearedslave revolts; after all, they had been taught that blacks were naturally savage.In the days following slavery, Harvard Professor Nathanial Southgate Shaler promotedhis theory of retrogression, causing some white Americans to fear that in freedomAfrican Americans would regress toward their natural barbaric state. White Americanshave used their fear to justify all manifestations of racism, including slavery,segregation, and paternalism.

Joel Williamson, in his book The Crucible of Race, reminds his readers that whiteracism has many faces, or mentalities. Specifically, Williamson traces three racialmentalities among whites in the southern post-bellum period: liberal, radical, andconservative. Racial liberals believed in the potential of African Americans; therefore,though few in numbers, they worked harder than any other group to ensure AfricanAmerican equality. Racial radicals existed at the other end of the continuum, believingAfrican Americans incapable of moving beyond their natural state of barbarism. Radicalgroups such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) found inspiration from Shalers theory andworked to purge America of African Americans. Racial conservatives existed in themiddle of the long continuum. Conservatives did not actively work for African Americanequality nor did they believe African Americans would naturally gravitate towarda natural barbaric and savage state. Conservatives actively engaged in paternalisticefforts to help African Americans stay in their white-relegated place in society.