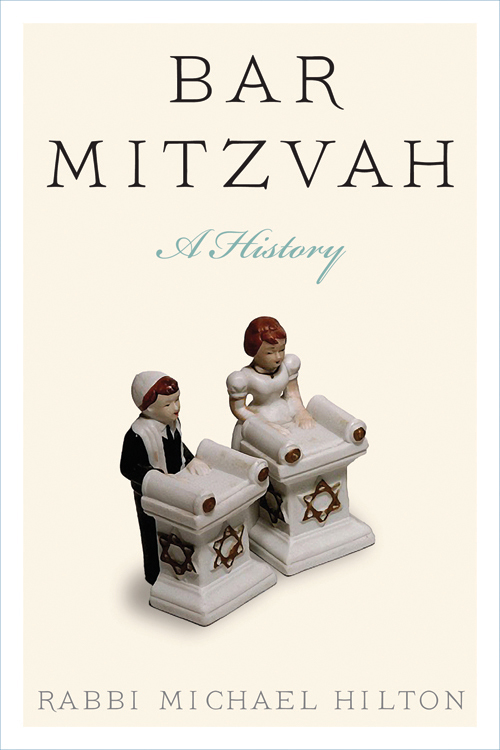

Michael Hiltons book combines a thorough grounding in the primary sources and scholarly literature about the history of bar mitzvah with the experience of an established congregational rabbi. For anyone seeking insight into the origins, development, and significance of this major Jewish lifecycle event, this is the book to consult.

Marc Saperstein, professor of Jewish history and homiletics at Leo Baeck College

Bar mitzvah and bat mitzvah are contemporary Judaisms best-known and least understood observances. Michael Hilton does a wonderful job of assembling the lore, laws, and customs regarding bar mitzvah and bat mitzvah in a way that is easily accessible to scholars, educators, and laypeople. Highly recommended!

Rabbi Jeffrey K. Salkin, author, Putting God on the Guest List: How to Reclaim the Spiritual Meaning of Your Childs Bar or Bat Mitzvah

Bar Mitzvah, a History

Bar Mitzvah

A History

Rabbi Michael Hilton

The Jewish Publication Society | Philadelphia

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London

2014 by Michael Hilton. Portions of this book originally appeared as Bar Mitzvah and Bat Mitzvah: A Reform Perspective Based on History (pamphlet), London: Movement for Reform Judaism, 2010; Israel Jacobson (17681828), in Great Reform Lives: Rabbis Who Dared to Differ, edited by Jonathan Romain, 1218. London: Movement for Reform Judaism, 2010; Jewish Confirmation, published in Research in Jewish Education in the UK: 2010 Conference Proceedings, edited by Helena Miller, 713. London: UJIA , 2010. All are used with permission.

Cover image courtesy National Museum of American Jewish History.

All rights reserved. Published by the University of Nebraska Press as a Jewish Publication Society book.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hilton, Michael.

Bar mitzvah, a history / Michael Hilton.

pages cm

Published by the University of Nebraska Press as a Jewish Publication Society book.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8276-0947-1 (paperback: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8276-1167-2 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8276-1168-9 (mobi)

ISBN 978-0-8276-1166-5 (pdf)

1. Bar mitzvah. I. Title.

BM 707. H 53 2014

296.4'42409dc23

2013050487

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For Samuel, Jacob, and Benjamin, benei mitzvah

Shabbat Lekh Lekha, 5761

Shabbat Bereshit, 5764

Shabbat Aharei-Mot Kedoshim, 5770

Contents

Illustrations

Table

Acknowledgments

This account could not have been written without the help and support of many scholars, libraries, and friends who have been kind enough to share personal reminiscences. In particular my thanks are due to my supervisor and guide, Dr. Sacha Stern at University College London ( UCL ); to scholar and academic Dr. Klaus Herrmann in Berlin; to my friend and fellow history researcher David Jacobs; and to my tireless editors at the Jewish Publication Society and the University of Nebraska Press, Carol Hupping and Elizabeth Gratch.

My thanks also to the many people who have assisted greatly by offering advice, finding sources, translating difficult texts, and reading drafts, especially Rabbi Marc D. Angel, Dr. Helen Beer, Rabbi Jeff Berger, Dr. Annette Bckler, Rabbi Barbara Borts, Vanessa Freedman, Rabbi Amanda Golby, Dr. Claire Hilton, Rabbi Yuval Keren, Yoav Landau-Pope, Rabbi Dr. Abraham Levy, Rabbi Josh Levy, Dr. Naftali Loewenthal, Miriam Rodrigues-Pereira, Rosita Rosenberg, Rabbi Professor Marc Saperstein, Dr. Jeremy Schonfield, Rabbi Dr. Michael Shire, Rabbi Daniela Thau, and Victor Seedman.

Help with photography has been kindly provided by Rabbi Frank Dabba Smith and help with finding illustrations by Fabian Graham and by the Temple Museum of Religious Art, the Temple-Tifereth Israel in Beachwood, Ohio. Figure 3 is reproduced with its permission, and figure 1 with the permission of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. The archives of West London Synagogue were consulted and are here quoted with permission.

Every library where I have conducted my research has been helpful, but the library of Leo Baeck College in London surpasses them all for being willing to obtain and even purchase rare material. I have also learned a great deal from comments made by those attending my lectures and seminars at Kol Chai Hatch End Jewish Community, the Liberal Jewish Synagogue, Leo Baeck College, Limmud, and elsewhere.

I owe a very special debt of gratitude to Kol Chai for generously allowing me time to study and sharing so many fascinating reminiscences. This book was researched and written in its entirety while I was serving as rabbi to Kol Chai. Bar mitzvah and bat mitzvah have been vital parts of its community life, as they have of mine.

Introduction

Laura Jean from Dallas, Texas, was twelve years old when she told her parents in 2003 that she would like a bat mitzvah: She loved bat mitzvahs: the singing was inspiring; the parties were exciting; the attention, no doubt, was flattering. Why couldnt she have one? The suggestion is that the African American parents want to express the same kind of pride in their children that they notice among Jewish families.

How did bar and bat mitzvah come to be so popular? What is it that appeals to Jews with totally different beliefs and lifestyles from each other and even to non-Jews? How did the ceremony start, and why is it that a higher proportion of Jewish children celebrate it today than at any time in the past?

The original ceremony, which was only for boys, was invented by fathers for their own sons. Bar mitzvah, many books tell us, means son of the commandment.the term was used in ancient times, before anyone had thought of celebrating a boys coming of age. The meaning of the term changed as the ceremony became important; it came to mean a Jewish boy aged at least thirteen and one day who from now on had the responsibility of carrying out all the religious duties of a Jewish man. In the twentieth century bar mitzvah changed its meaning again and came to refer to the celebration, rather than the child. In English today this is what the phrase means, and the child is called the bar mitzvah boy or the bat mitzvah girl.

If you attend a boys bar mitzvah today, you are likely to see some or all of four traditional elements that have been combined into a single sequence for the last four hundred years. First, during the synagogue service the boy is called up to the Torah to say the traditional blessings and, if he is able, to read or chant his own portion from the Torah scroll, instead of the usual weekly practice of it being read by a skilled volunteer or professional. In the main Ashkenazic tradition followed today in Israel, much of Europe, and in English-speaking lands, the boy is called up for maftir and haftarah on Shabbat morningthat is to say, on a Saturday morning in the synagogue, after the whole of the weeks section has been read and seven adult men called to the Torah, the bar mitzvah recites the blessing before reading the Torah, repeats the prescribed last few verses that have already been read, recites the blessing after reading the Torah, and then reads the prescribed reading from the Prophets, with blessings said before and after.

The blessings recited by the bar mitzvah are the same ones said by everyone called up to the Torah. Before the reading the boy says, Bless the Eternal whom we are called to bless. The congregation responds, Blessed is the Eternal whom we are called to bless forever and ever. The boy repeats the response and then carries on, Blessed are You, our Eternal God, Sovereign of the Universe, who chose us from all peoples to give us your Torah. Blessed are You, Eternal One, who gives us the Torah.

Next page