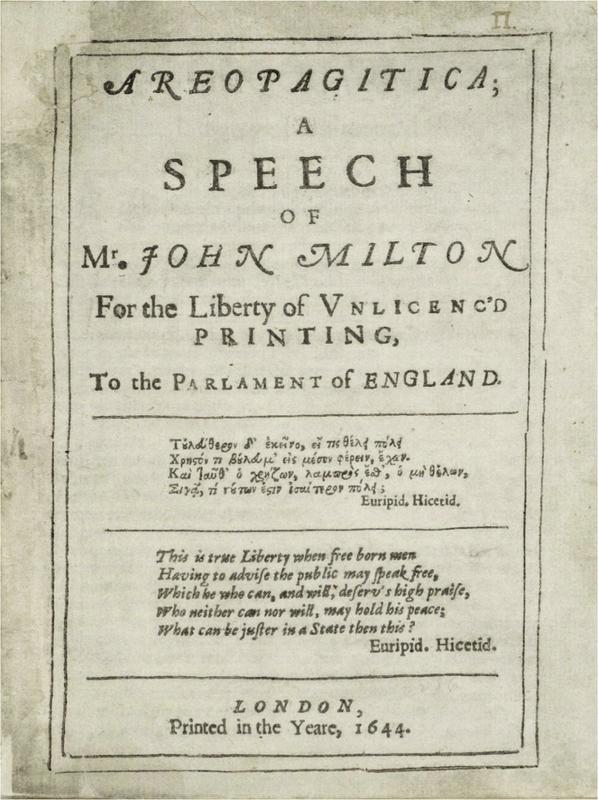

One of the books that I had to read in 1952 for the Higher School Certificate which was to become the A Level was Miltons Areopagitica. As I had never heard of it before, and as it had an uninviting Greek title and I hadnt studied Greek, and since it is a long essay, it didnt look as interesting as the other books we had to read: King Lear, The Tempest, The Rape of the Lock, The Lyrical Ballads and The Woodlanders. So I left it to the end. But I was soon enthralled by Miltons passionate and eloquent condemnation of censorship and his assertion of the right of every individual to think, write and speak freely for that was to him the essence of personal and political freedom.

Miltons arguments were compelling but what made his great prose memorable for me was his eloquence in fashioning phrases and sentences that have resonated throughout history and are just as significant and relevant today:

As good almost kill a man as kill a good book. Who kills a man kills a reasonable creature, Gods image; but he who destroys a good book, kills reason itself, kills the image of God, as it were in the eye.

Give me the liberty to know, to utter, to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties!

A good book is the precious life-blood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.

Books are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are; nay they do preserve as in a vial the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them.

The lack of freedom of expression that rankled with Milton was Charles Is censorship of books and pamphlets, which led to their authors being pilloried or having their ears cut off or their noses split. He argued against the authority of the Star Chamber with its Imprimaturs Let it be printed and its Nihil Obstats Nothing stands in its way. One of the many tragedies of Miltons life was that he was to see his words in Areopagitica ignored and even rejected by his friends. The Puritans of the Long Parliament were little better, for they banned all stage plays in 1642 and in 1644 they passed an Act to regulate printing; it was this that prompted Milton to write Areopagitica.

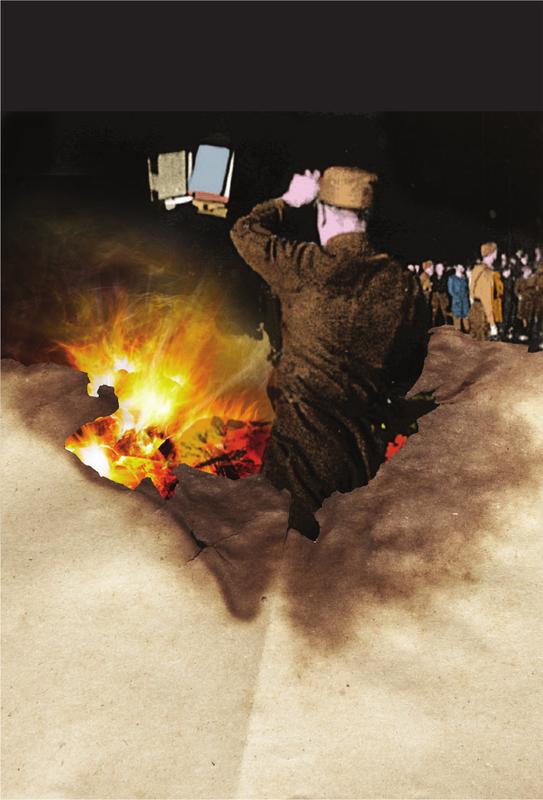

His hero, Oliver Cromwell, was just as censorious as Charles I. The Puritans smashed beautiful stained-glass windows, lamented by George Herbert in his poem The Windows, and they banned and burnt books as well.

The title page of Areopagitica, 1644.

To Milton the book was sacred, as it combined the memory of the past with a prospect of a life extending over centuries to come, and this really started my long love affair with books. Their significance has been recognised in many civilisations throughout the world and throughout history. In the Abbasid Caliphate of the ninth century the great Arabic scholar Al Jahiz, born in Basra and writing mainly in Baghdad, observed:

The composing of books is more effective than building in recording the accomplishments of the passing ages and centuries. For there is no doubt that construction eventually perishes and its traces disappear, while books handed down from one generation to another and from nation to nation remain ever renewed. Were it not for the wisdom garnered in books most of the wisdom would have been lost. The power of forgetfulness would have triumphed over the power of memory.

In the twentieth century Jorge Luis Borges said, Of all mens instruments the most outstanding is, without any doubt, the book. The others are extensions of his body. The microscope, the telescope are extensions of his eyes; the telephone an extension of his voice, then we have the plough and the sword extensions of his arm: the book is extension of memory and imagination. The key word is memory: for a book is not just a compendium of information, it also preserves the collective memory of its people with its foundation myths and fables, telling of its heroes and of battles won. It is the collective memory that any conqueror has to destroy. In Rome the Senate expunged the memory damnatio memoriae of those who had as traitors brought shame upon the city. George Orwells totalitarian government in 1984 had a department whose duty it was to collect books on the written record of the past, to be burnt in secret furnaces. Ray Bradbury in his novel Fahrenheit 451 (the temperature at which books burn) envisages a future America where all books are burnt, as they are old-fashioned, irrelevant or subversive. But there is a group of book drifters exiled to the country, where each learns a book by heart, so that the collective memory of America is preserved and one day they can be printed again.

Book burning has been so extensive and so perverse in its effect that I started to keep a note of the occurrences I came across which is how this book has come about. It does not attempt to be a comprehensive collection of all the many instances of mans folly there are other studies that list all the libraries and collections, great and small, that have been destroyed and the individual volumes consigned to the flames. Such studies are usually written by scholars and librarians for scholars and librarians.

As books have been victims throughout history I decided to focus on those events where books have been burnt quite deliberately for political, religious or personal reasons, as the motive behind their destruction is what has interested me. It is a personal anthology.

One of the first things I discovered was that those who inspired or organised the destruction of books were not louts, looters or thugs, but well-educated people often scholars who would have described themselves as civilised, just like the German professors who instructed their students to follow Goebbelss order to burn certain un-German books. They all had a common characteristic a conviction that their views must prevail, since theirs was the one certain route either to personal salvation or to political stability. If the retention of power, whether in a church, a mosque, a temple or a castle or cabinet room, was threatened by the written word, then throwing dangerous and offensive publications on the fire was the necessary first step to retain, enhance, defend and extend their power.

The power of religions or political regimes derives from their leaders absolute conviction that what they are doing is right. It is this moral certainty that has driven so many religions and regimes to impose belief, to compel obedience, to censor and burn books, to spy on dissidents, to imprison, to torture and to kill. Totalitarian regimes whether Fascist, Communist or Nationalist and fanatics nurtured by fundamentalist religions become so convinced of the utter correctness of their own position that they can justify the burning, the elimination of dissidents and today the public beheading of prisoners. This certainty was behind the Inquisition in Spain, Calvin in Geneva, Stalin in Russia, Hitler in the Third Reich, Mao in China, the Stasi in East Germany, the Generals in Brazil and Argentina and today the Taliban, Al-Qaeda and ISIS.