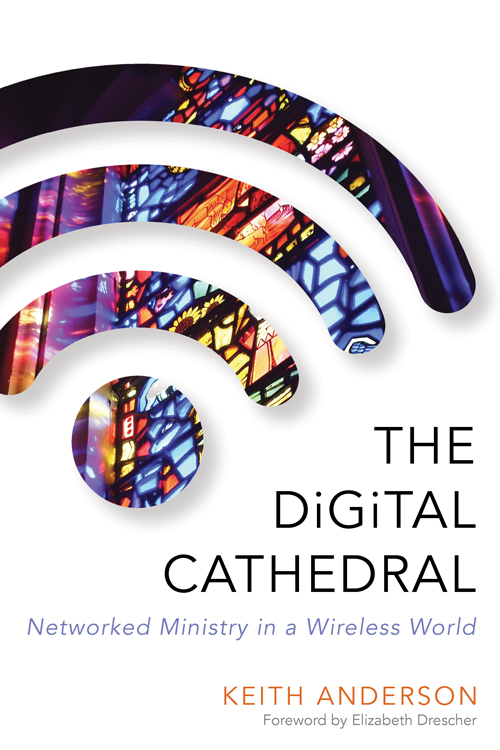

Copyright 2015 by Keith Anderson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

Unless otherwise noted, the Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Morehouse Publishing, 19 East 34th Street, New York, NY 10016

Morehouse Publishing is an imprint of Church Publishing Incorporated.

www.churchpublishing.org

Cover design by Laurie Klein Westhafer

Typeset by Rose Design

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Anderson, Keith, 1949

The digital cathedral : networked ministry in a wireless world / Keith Anderson.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8192-2995-3 (pbk.)ISBN 978-0-8192-2996-0 (ebook) 1. Pastoral careData processing. 2. Internet in church work. 3. Social media. I. Title.

BV4011.9.A53 2015

253.0285'675dc23

2014047353

Printed in the United States of America

In thanksgiving to the living God for all ministers who have borne

the hot coal of [Gods] Word upon their lips and in their lives.

Inscription at Washington National Cathedral

SOME YEARS AGO, in my late twenties, I worked for a while in England as a management consultant. I had a little basement flat in London, on Dorset Square, just around the corner from Sherlock Holmes digs at 221B Baker Street. I was an easy walk away from the enchantments of Regents Park and at least a half a dozen amazing Indian take-away shops. My London pied--terre had all the makings of a remarkable locale for a young woman abroad were it not for the fact that I traveled outside of London most weeks to dank office buildings or soulless industrial parks in Birmingham, Blackpool, Coventry, Lincoln, Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield, and so on. And I worked such long hours that I was almost always exhausted by the time I got back to my humble flat, very late most Friday evenings. As I dragged myself to bed, I barely felt the rattle of the underground trains as they passed beneath me on their way from Baker Street to Marylebone Station.

It turns out that, while jumbling up corporations across the globe can sound like an exciting job, it was something of an overwhelming grinddays following around hapless middle managers to see where their work might be made more efficient (and they might be rendered redundant); hours coaching executives on everything from globalization strategies to modes of leadership that would improve employee productivity; late nights pouring over organization charts, financial reports, and personnel files. All of that made the experience for me, even then in my decidedly unreligious and only vaguely spiritual days, profoundly soul sucking. The only salvation from this was, ironically, Sunday.

Sundays truly were Sabbath for me. Having caught up on sleep and done sundry chores and errands on Saturdays, Id wake early on Sunday mornings and take the train to Canterbury. I did it almost every week for the better part of a yearan hour and a half of tea and quiet through the countryside from London to Kent. Once I got to the station in Canterbury, if the weather was reasonably fair, Id wend my way into the center of town to the famed cathedral, varying my routes to take in more of the storied city where the blood of Thomas Becket was shed and, on route to which, more famously, Chaucers fictional pilgrims spun their many wondrously tawdry tales. Most Sundays, Id stop at one of any number of small bookshops that dotted the city back thenthey all seem to have become Starbucks these dayswhere Id pick up (yet another) pocket copy of The Canterbury Tales, or perhaps something from the anonymous Pearl Poet of Sir Gawain fame, or a dry bit of something from Chaucers less celebrated friend, moral Gower. Every so often, Id come upon an ancient seeming illuminated psalter or a slightly mildewed Book of Common Prayer, but I seldom took the baittoo overtly religiousy for my tastes at the time, though I would take a spiritual lean once in a while. I found Julian of Norwich for the first time in Canterbury that year; and, the strangely compelling lay mystic and pilgrim Margery Kempe literally jumped off a shelf in a little shop on Longmarket, nearly smacking me in the head. Mostly, it was Chaucer, though, who Id take with me to some nook in the cathedral, where, often as the boys choir rehearsed, Id let the round, guttural Middle English syllables roll with whispered ineptitude off my tongue.

One particularly stunning Sunday morning in August, as I sat outside in the Cloisters reading, as ever, from The Tales, I was greeted by a young cleric. He invited me to the Holy Communion service that was to begin shortly. No thank you, I said. Im just reading my book.

Oh, he smiled, we have lots of books. Were a very bookish sort of church.

Well, yes, I sighed a little, I suppose thats true. But Im not really religious.

Ah, he said finally, smiling still as he turned back toward the cathedral, and yet here you are with your pious pilgrims.

I shrugged off his quip at the timeit would be a few more years before my pilgrimage would take me, a wobbly sort of believer, into a church for services proper. As the bells rang for the service, I gathered my things and made my way to a nearby tea shop, where I would commit the heresy of insisting on weak American tea (bag dipped briefly into the steaming water rather than steeped robustly in it for long minutes) and eavesdrop on the tales of random fellow pilgrims. Most weeks, someone would strike up a conversation with me as I doodled in a notebook or looked up from my reading. Our stories would weave together for a few moments over a simpler communion of tea and scones that, nonetheless, held a certain air of the holy.

It was, indeed, a religious practice, these regular trips to Canterbury, if by religious we mean something vaguely ritualized in time, locale, and the general order of activities. It was religious, too, as a claim on sanctuaryon a place where one is immune from the persecutions of everyday life, especially the constant pull of progress and improvement that were so much a part of my profession at the time. The reflective quiet I found within the precincts of Canterbury Cathedral; the freedom to amble around the town through secreted gates and back alleys cobbled with centuries old stones; the hours spent sipping tea while listening in on the lives of strangers from around the world; and, not least, the strange and alluring voices of medieval English poets and the occasional spiritual writer were all as much a part of my religious formation as any inquirers class in a drafty church hall might have been. When I eventually made my way to an Episcopal church in Pennsylvania several years later, it was clear to me that I owed my conversion, such as it was, as much to Chaucer as to Christ, as much to Canterbury as to Calvary. Canterburythe cathedral; the history, legends, and literatures that emanate from it; and the city in which it is centered at a busy intersection of past, present, and futureconnected me to an idea of the past, to a rich tradition, and to a widely distributed and diverse community that reached into and well beyond the particularities of my personal experience. Sociologist of religion Danile Hervieu-Lge refers to such connections as links on a religious chain of memory.