Rethinking

Human Nature

Rethinking

Human Nature

A CHRISTIAN MATERIALIST

ALTENATIVE TO

THE SOUL

KEVIN J. CORCORAN

2006 by Kevin J. Corcoran

Published by Baker Academic

a division of Baker Publishing Group

P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287

www.bakeracademic.com

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meansfor example, electronic, photocopy, recordingwithout the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Corcoran, Kevin, 1964

Rethinking human nature : a Christian materialist alternative to the soul / Kevin J. Corcoran.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 10: 0-8010-2780-2 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-8010-2780-2 (pbk.)

1. Philosophical anthropology. 2. Man (Christian theology). 3. Christianity Philosophy. I. Title.

BD450.C635 2006

128dc22

2005037188

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations labeled NIV are from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION. NIV. Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved.

In Memoriam

Patrick G. Corcoran

(193268),

the father I never got to know,

and

Samuel J. Baum

(19562004),

faithful friend, dearly loved

Contents

I WISH TO ACKNOWLEDGE THE FOLLOWING journals and people for kindness and generosity. Parts of chapter 3 previously appeared as Persons, Bodies, and the Constitution Relation, Southern Journal of Philosophy 37 (1999): 120. Part 1 of chapter 4 borrows heavily from my Material Persons, Immaterial Souls, and an Ethic of Life, Faith and Philosophy 20 (2003): 21828. Material in chapter 5 previously appeared as Dualism, Materialism, and the Problem of Post Mortem Survival, Philosophia Christi 4 (2002): 395409. I thank these journals for permission to include that material here.

Writing this book was made enormously pleasurable largely because it was written in conversation with people I know and love. Some of them (perhaps even most) do not agree with the view of human nature I defend in these pages. But all of them provided invaluable, generous assistance.

First, Steve and Susan Matheson provided exceptionally good, incisive feedback. Steve is a biologist and Calvin colleague, and he helped save me from making many errors in the discussion of embryology and stem cell research covered in chapter 4. Whatever errors remain in those sections exist in spite of Steves best efforts. Susan read both an early and a penultimate draft of the entire manuscript and provided excellent feedback. Again, whatever deficiencies remain do so in spite of Susans best efforts to help spare me embarrassment.

I thank, too, my good friend Ron Scheller, who, like Susan, is exactly the kind of reader I am aiming for in this book. Ron is not a professional philosopher or a theologian, but he has the virtue of being naturally inquisitive, and he enjoys a rigorous intellectual workout. His comments, objections, and criticisms on the material in chapter 4 were enormously helpful. Where I failed to heed the sober advice of Ron and Susan, it is probably my undoing.

Greg Ganssle is another good friend. Greg forced me to rethink, rearrange, and reconsider many of the matters I take up in these pages. It is truly no exaggeration to say that this book would be much the worse if not for Gregs helpful, fair, and often humorous feedback on the entire manuscript.

Thanks are also due to two anonymous readers who provided helpful feedback on the manuscript.

Finally, I thank my dear friend Samuel Baum, who discussed with me all the issues addressed in this book and lots more over the course of a seventeen-year friendship. Sam passed away before I could bring the book to completion.

Introduction

WHAT KIND OF THINGS ARE WE ?

IN 1968 , I LOST MY father to cancer. I was four years old. I can still remember the funeral home. And I can remember that as I looked into the casket my mother told me that my father was now with God in heaven. I remember being perplexed. And why not? For all appearances, my father was lying lifeless before me. How could he be with God in heaven? Now I understand that my mother believed what most Christians have believed down through the centuries, namely, that we human persons are immaterial souls. According to this view, my fathers lifeless body may have been lying before me but not my father. For although we human persons may be contingently and tightly joined to human bodies during the course of our earthly existence, so the view goes, we can, and in fact one day will, exist without them.

During the final stages of writing this book, I lost a dear friend to a malevolent brain tumor. I watched as the tumor and the medications used to treat the tumor ravaged his body, stole his short-term memory, and radically altered his appearance and personality. The destruction was complete in a matter of months. Through much of his short illness, my friend and I explored together, as we had done for so many years, some of the more obvious possibilities concerning what we human persons most fundamentally are: We are immaterial souls; we are material bodies; we are a composite of immaterial soul and material body. We explored as well some not so obvious alternatives.

The topics we discussedwhether we human persons are or have immaterial souls capable of disembodied existence or whether we are merely human animals ultimately destined to dusthave long been topics of interest to professional philosophers, theologians, social scientists, and ethicists. But they have also been topics of interest to ordinary peopleto four-year-old children trying to understand what happened to Daddy when Daddy is said to have died and to forty-eight-year-old computer programmers struggling to comprehend their quick and tragic disintegration.

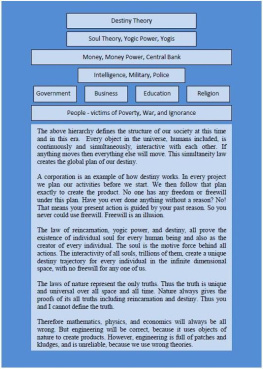

Augustine (AD 354430) and Ren Descartes (15961650) believed what my mother believes: that we are immaterial souls. My friend Sam, a man with a unique blend of Jewish and Eastern beliefs, believed something along these lines too. Despite a few dissenting voices, however, today the dominant view among professional philosophers, ethicists, neurobiologists, psychologists, and cognitive scientists is a nothing but version of materialism, the view that creatures like us are nothing but complicated neural networks or mere biological beasts.

The question of human nature ought to concern us all. Human cloning, tissue transplant therapies, stem cell research, and other genetic and reproductive technologies are reigniting debate about the issue of personhood and human nature and revealing the urgency and importance of careful thinking about the topic for ordinary people. Indeed, it is ordinary people who must make very practical, and often very gut-wrenching, beginning of life ethical decisions. Moreover, the question of human nature obviously touches on beliefs central to orthodox Christianity, such as belief in life after death and the claim that we human beings have been created in the image of God.

The central question addressed in the following pages, then, is the metaphysical question that Augustine ponders in book 7 of his

Next page