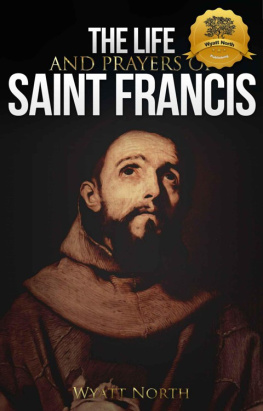

A Portrait of St. Francis

He was quite an eloquent man, with a cheerful and kindly face. He was without cowardice or insolence. He was less than medium in height, bordering on shortness. His head was of moderate size and round, his face somewhat long and striking, with a smooth, low forehead. His eyes were black and clear and of average size; his hair was black and his eyebrows straight, his symmetrical nose was thin and straight. His small ears stood up straight and his temples were smooth. His speech was peaceable, but fiery and crisp; his voice was strong, sweet, clear, and sonorous. His teeth were closely fitted, even, and white; his lips were small and thin; his beard was black and not bushy. He had a slender neck, straight shoulders, short arms, slender hands with long fingers and extended nails; his legs were thin, his feet small. He had delicate skin and was quite thin. He wore rough garments, slept sparingly, gave most generously. And because he was very humble, he showed mildness to everyone, adapting himself to the behavior of all. Among the holy he was even more so; among sinners he was one of them.

Celano, First Life, 83

Introduction

1

I have been on a spiritual journey to and with St. Francis since my thirteenth year, and most of the selections in this book were made on actual pilgrimages to Assisi. Therefore what I say here in this introduction and the daily entries themselves are after the manner of a notebook from a pilgrim who has drawn on the words of St. Francis to guide him on lifes way.

The way of pilgrimage is the way of death leading to life. You leave behind loved ones and home, entrusting their safety and care to God, who is drawing you away from them. It is God who leads the pilgrim as he leads the dying person, and you follow shyly, awkwardly, fearfully, at first; then letting go somewhere along the way, you surrender what youve left behind into the very hand that is clasping yours on the journey.

An image of all this rises in my mind, a poem by the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke entitled The Swan:

This laboring through what is still undone,

as though, legs bound, we hobbled along the way,

is like the awkward walking of the swan.

And dyingto let go, no longer feel

the solid ground we stand on every day

is like his anxious letting himself fall

into the water, which receives him gently and which, as though with reverence and joy, draws back past him in streams on either side; while, infinitely silent and aware, in his full majesty and ever more indifferent, he condescends to glide.

It is not so much where you are going as the going away, the leaving itself, that matters. It is consigning to God what you thought was so dependent on your presence: your loved ones, your affairs. You leave, not knowing for certain that you will return. You embark upon a journey of faith, from faith to faith.

It is not that one place on earth is more in Gods hearing than another, so that he hears me better there than here. But it is what happens to my own hearing in traveling there to listen, when the things and people of here begin to speak too loudly for me to hear my own inner voices and the voice of the Spirit.

In the Middle Ages those who went on pilgrimage wondered if they would ever return; the slowness of the journey and the dangers along the way made reaching ones destination doubtful. Today the pace is fasterjet travel, telephone communication with ones loved ones back homerealities that make our pilgrimage seem less radical, less drastic a decision than it was in ages past. And in one sense that is true.

In another sense, however, nothing has changed. There is still the decision to set forth on ones own in the company of strangers, in order to lay ones ear, opened along the way, against the mouth of God that spoke once in the place or through the person whose shrine we are drawn to.

And somehow we go alone, even if we are in the company of others, even of our loved ones. For our journey is largely made in the heart (perhaps from the mind to the heart), an inner rather than an outer journey. The outer journey can indeed be made with others; the inner cannot, though perhaps the words of someone living or dead may make our journey seem less solitary.

And so it has been and is, that I bring with me on all my travels the words of St. Francis. They are food for the journey because most of them were written or spoken for those who are on the road, so to speak, mendicants, beggars who travel two by two throughout the world, though inwardly they are hermits, because, as St. Francis says, they carry their cell with them. He envisions the brothers as pilgrims on the road, and what he says is like practical advice for those who are constantly leaving something or someone behind.

Unlike the usual idea of a pilgrim, however, St. Franciss conception is not of someone going to a place made holy by others; rather, it is of those who make every place holy in their going there. His words are a way of making holy the journey to anywhere. His words sanctify the way.

As we journey through life, we not only leave something behind, but we gain something as well. Like Rilkes swan, infinitely silent and aware, in full majesty and ever more indiffrent, we condescend to glide.

In essence, that is what the words of St. Francis, when put into practice, enable us to do. And it is God in whom we glide so easily, the God we feared, the God we perhaps did not think was there anymore as we labored out of our element like swans on land looking for water.

We learn that the water is there, that it is not so frightening as we thought, that if we let go, we will begin to glide easily, gracefully, to where we one day will remain forever. Pilgrimage is a testing of the waters of eternity. And the words of St. Francis make that testing less frightening; they make it, in fact, exciting. In the spoken and written experience of St. Francis we discover someone who lives comfortably in the waters of eternity, even while on earth.

There is always in the pilgrims way the way of the penitent. For as we embark upon a journey to God, we are immediately aware of how far we really are from him for whom we long, toward whom we are journeying. That is the main reason why the words of St. Francis sound at times rather negative, rather deprecatory of what is earthly, even of what is human.

He is not saying that the body, the world, the human person are evil. He is only saying that apart from God, without God, in comparison to God, we and everything else that exists are really nothing. Of ourselves we are worthless and vile. Of ourselves, on our own, as it were.

St. Franciss viewpoint is that of someone whose journey has led him into another dimension, the world of the Spirit, which completes and makes intelligible all that is. He sees the whole picture and is therefore unimpressed with the works and deeds of humankind. He sees human beings in the total scheme of thingshow insignificant they really are compared to the Most High, Omnipotent, Good God, who alone is Good, who alone is God.

We who live for the most part on the human level find it hard to stomach some of the things St. Francis says, because we tend to affirm and celebrate only what is thoroughly human: human goodness, human dignity, human worth. All of which is valid and gooduntil you move into that other world within our world, the world of Gods Spirit. For you cannot experience that world by human effort, or goodness. Only God can take you there, and his leading you begins with an experience of conversion which humbles you before the Good God, an experience which opens up for you the infinite chasm between Creator and creature.