Gerrard Winstanley

Revolutionary Lives

Series Editors: Brian Doherty, Keele University; Sarah Irving, University of Edinburgh; and Professor Paul Le Blanc, La Roche College, Pittsburgh

Revolutionary Lives is a book series of short introductory critical biographies of radical political figures. The books are sympathetic but not sycophantic, and the intention is to present a balanced and where necessary critical evaluation of the individuals place in their political field, putting their actions and achievements in context and exploring issues raised by their lives, such as the use or rejection of violence, nationalism, or gender in political activism. While individuals are the subject of the books, their personal lives are dealt with lightly except in so far as they mesh with political issues. The focus of these books is the contribution their subjects have made to history, an examination of how far they achieved their aims in improving the lives of the oppressed and exploited, and how they can continue to be an inspiration for many today.

Published titles:

Leila Khaled: Icon of Palestinian Liberation

Sarah Irving

Jean Paul Marat: Tribune of the French Revolution

Clifford D. Conner

www.revolutionarylives.co.uk

First published 2013 by Pluto Press

345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

www.plutobooks.com

Distributed in the United States of America exclusively by

Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martins Press LLC,

175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010

Copyright John Gurney 2013

The right of John Gurney to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 3184 3 Hardback

ISBN 978 0 7453 3183 6 Paperback

ISBN 978 1 8496 4676 5 PDF eBook

ISBN 978 1 8496 4678 9 Kindle eBook

ISBN 978 1 8496 4677 2 EPUB eBook

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services Ltd

Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England

Simultaneously printed digitally by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, UK and Edwards Bros in the United States of America

To Rachel, Thomas and Anna

Contents

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Ann Hughes for suggesting that I write this book, and to David Castle and Brian Doherty for all their expert advice and help. In the course of working on the book I have had valuable exchanges on Winstanley with Scott Ashley, Fabrice Bensimon, Andrew Bradstock, Jeremy Boulton, Ian Bullock, Fergus Campbell, Colin Davis, Martyn Hammersley, Rachel Hammersley, Ariel Hessayon, Geoff Horn, Ann Hughes, William Lamont, David Taylor and Derek Winstanley, and I am grateful to them all. Rachel, Thomas and Anna have been immensely supportive and patient throughout this book is dedicated to them, with love.

1

Introduction

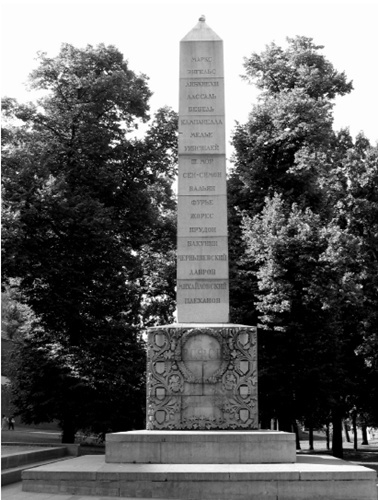

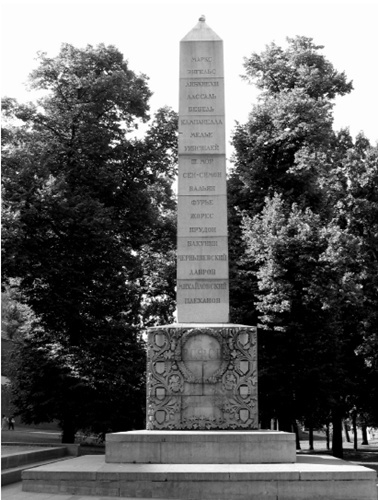

In the summer of 1918, as the first anniversary of the October Revolution approached, steps were taken in Moscow to implement one of Lenins pet projects, his plan for monumental propaganda. According to a decree that had been issued on 12 April, surviving symbols of the Tsarist regime were to be systematically removed, and monuments to past revolutionary thinkers and activists set up along major routes in the metropolis. Similar plans were laid for Petrograd. Among the old Tsarist symbols which faced destruction was a large granite obelisk standing prominently in the Alexander Gardens by the Kremlin, and which had been erected as recently as 1913 to commemorate 300 years of Romanov rule. It was Lenin who took the decision to save the obelisk, when it became clear that re-use might be preferable to demolition. As civil war in Russia intensified, work on new monuments had proved much more difficult than expected, and it was apparent that few would be ready for the first anniversary celebrations. It made good sense to recycle an older monument, even at the risk of upsetting Moscows avant-garde artists and sculptors. The Romanov two-headed eagle was removed from the Alexander Gardens obelisk, and the names of tsars were effaced; in their place the names of 19 leading revolutionary thinkers were inscribed. As might be expected, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels headed the list, but the eighth name was that of Uinstenli, or Gerrard Winstanley (160976), best known as leader of the seventeenth-century English Diggers, who in April 1649 had occupied waste land at St Georges Hill in Surrey, sowed the ground with parsnips, carrots and beans, and declared their hope that the Earth would soon become a common treasury for all, without respect of persons.

The Alexander Gardens obelisk, Moscow. Winstanley is eighth on the list, after Marx, Engels and other leading revolutionary thinkers. Credit: Mitrius (wikimedia commons).

Why should Lenin and his associates have chosen Winstanley as one of the thinkers whose work might be seen to have helped pave the way for the massive upheavals of October 1917? What was it that brought Winstanley into this Pantheon of

Winstanley was a religious thinker and visionary, strongly influenced by the mystical writings that were so popular among radicals in the English Revolution; his work was suffused with biblical quotation and he shared fully in the millenarian excitement of the age. In many ways there was a world of difference between him and late nineteenth-century Marxists. Yet it is possible to understand how the latter might come to take an interest in Winstanley and to see in him a precursor, however distant, of Marx. Winstanleys views were always distinctive: he chose to use the word Reason in place of the word God, he insisted that humanity and the whole creation had been corrupted by covetousness, competitiveness and false dealings, and he anticipated a time when all would come to

Winstanleys appeal to Marxists lay not only in his perceptive social criticism, but also in his recognition of the importance of agency and self-emancipation. Like many seventeenth-century radicals Winstanley proclaimed his preference for action over words, but while some radicals advocated charitable help for the poor, Winstanley was insistent that the poor should take responsibility for freeing themselves from their burdens. The actions of the poor in working the land in common, and in refusing to work for hire, would both signal the impending changes and help usher them in. Marxist readers of Winstanley, deeply engaged as many of them were in the political struggles of their own time, would find no difficulty in endorsing Winstanleys

In his religious writings too Winstanley might be seen to have gone further than many of his contemporaries. His deep anticlericalism was directed not only against the institutions and personnel of the established church, but against all organised religion, including the radical sects. Marxists encountering Winstanley for the first time would welcome Winstanleys fierce criticism of the social functions of religion, and of versions of Christianity that focused primarily on individual salvation. It was actions here on earth, rather than any promise of future salvation, that for Winstanley formed the essence of true religion; the question of the existence of heaven or hell was consequently of lesser concern to him. While most historians today would identify Winstanleys religious position as an extreme example of a belief in a religion of conduct, it is easy to understand why turn-of-the-century Marxists might see him as many of his contemporaries had as at heart an atheist, and as someone who used religious language principally to cloak secular arguments. In this, as in so many other ways, Winstanley could appear to them to be one of the most interesting forerunners of modern scientific socialism.