Wisdom Publications

199 Elm Street

Somerville, MA 02144 USA

www.wisdompubs.org

2005 Khao Suan Luang Dhamma Community

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any other information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

K. Khaosanlang (K Khaoanlang), 1901-1978.

[Selections. English. 2005]

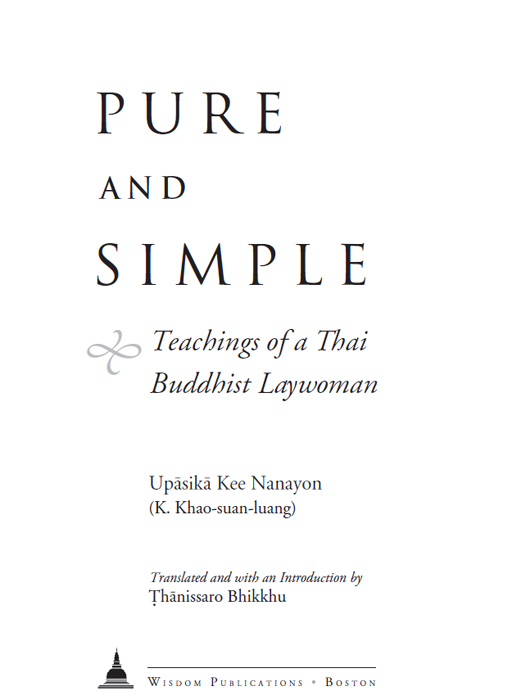

Pure and simple : teachings of a Thai Buddhist laywoman / Upsik Kee Nanayon (K. Khao-suan-luang) ; translated and with an introduction by Thanissaro Bhikkhu.

p. cm.

In English, translated from Thai.

The passages translated here are taken from Upsik Kees extemporaneous talksIntrod.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-86171-492-X (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. MeditationBuddhism. 2. BuddhismDoctrines. I. Title: Pure and simple. II. DeGraff, Geoffrey. III. Title.

BQ5625.K65 2005

294.3444dc22

2004029380

First Edition

09 08 07 06 05

5 4 3 2 1

Cover design by Suzanne Heiser.

Interior design by Dede Cummings. Set in Centaur Mt 11.5/16.25.

Wisdom Publications books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability set by the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Printed in Canada.

CONTENTS

Mindfulness Like the Pilings of a Dam

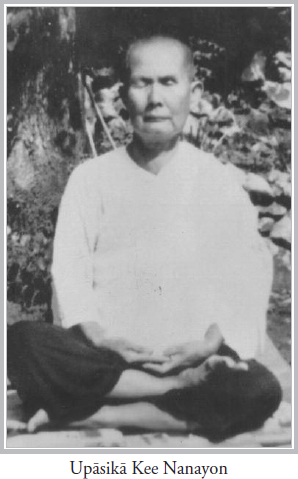

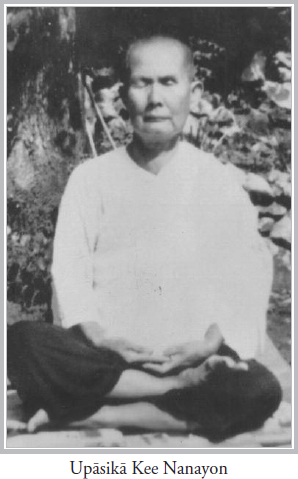

Upsik Kee Nanayon, also known by her pen name, K. Khao-suan-luang, was the foremost woman Dhamma teacher in twentieth-century Thailand. Born in 1901 to a Chinese merchant family in Rajburi, a town to the west of Bangkok, she was the eldest of five childrenor, counting her fathers children by a second wife, the eldest of eight. Her mother was a religious woman and taught her the rudiments of Buddhist practice, such as nightly chants and the observance of the precepts, from an early age. In later life she described how, at the age of six, she became so filled with fear and loathing at the miseries her mother went through during the pregnancy and birth of one of Kees younger siblings that, on seeing the newborn child for the first timesleeping quietly, a little red thing with black, black hairshe ran away from home for three days. This experience, plus the anguish she must have felt when her parents separated, probably lay behind her decision, made when she was still quite young, never to submit to what she saw as the slavery of marriage.

Upsik Kee Nanayon, also known by her pen name, K. Khao-suan-luang, was the foremost woman Dhamma teacher in twentieth-century Thailand. Born in 1901 to a Chinese merchant family in Rajburi, a town to the west of Bangkok, she was the eldest of five childrenor, counting her fathers children by a second wife, the eldest of eight. Her mother was a religious woman and taught her the rudiments of Buddhist practice, such as nightly chants and the observance of the precepts, from an early age. In later life she described how, at the age of six, she became so filled with fear and loathing at the miseries her mother went through during the pregnancy and birth of one of Kees younger siblings that, on seeing the newborn child for the first timesleeping quietly, a little red thing with black, black hairshe ran away from home for three days. This experience, plus the anguish she must have felt when her parents separated, probably lay behind her decision, made when she was still quite young, never to submit to what she saw as the slavery of marriage.

During her teens she devoted her spare time to Dhamma books and to meditation, and her working hours to running a small store to support her father in his old age. Her meditation progressed well enough that she was able to teach him meditation, with fairly good results, in the last year of his life. After his death she continued her business with the thought of saving up enough money to enable herself to live the remainder of her life in a secluded place and give herself fully to the practice. Her aunt and uncle, who were also interested in Dhamma practice, had a small home near a forested hill, Khao Suan Luang (Royal Park Mountain, the place that inspired her choice of pen name), outside of Rajburi, where she often went to practice. In 1945, as life disrupted by World War II had begun to return to normal, she handed her store over to her younger sister, joined her aunt and uncle in moving to the hill, and there the three of them began a life devoted entirely to meditation, taking on the titles of upsaka and upsikmale and female lay devotees of the Buddha. The small retreat they made for themselves in an abandoned monastic dwelling eventually grew to become the nucleus of a womens practice center that has flourished to this day.

Life at the retreat was frugal, in line with the fact that outside support was minimal in the early years. However, even now that the center has become well known and fully established, the same frugality is maintained for its benefitssubduing greed, pride, and other mental defilementsas well as for the pleasure it offers in unburdening the heart. The women practicing at the center are all vegetarian and abstain from such stimulants as tobacco, coffee, tea, and betel nut. They meet daily for chanting, group meditation, and discussion of the practice. In the years when Upsik Kees health was still strong, she would hold special meetings at which the members would report on their practice, after which she would give a talk touching on important issues they had brought up in their reports. It was during such sessions that most of the talks recorded in this volume were given.

In the centers early years, small groups of friends and relatives would visit on occasion to give support and to listen to Upsik Kees Dhamma talks. As word spread of the high standard of her teachings and practice, larger groups came to visit and more women joined the community. Although many of her students were ordained eight-precept nuns, robed in white, she herself maintained the status of an eight-precept laywoman all her life.

When tape-recording was introduced to Thailand in the mid-1950s, friends began recording her talks, and in 1956 a group of them printed a small volume of her transcribed talks for free distribution. By the mid-1960s, the stream of free Dhamma literature from Khao Suan LuangUpsik Kees poetry as well as her talkshad grown to a flood. This attracted even more people to her center and established her as one of the best-known Dhamma teachers, male or female, in Thailand.

Upsik Kee was something of an autodidact. Although she picked up the rudiments of meditation during her frequent visits to monasteries in her youth, she practiced mostly on her own without any formal study under a meditation teacher. Most of her instruction came from booksthe Pali Canon and the works of contemporary teachersand was tested in the crucible of her own relentless honesty.

In the later years of her life she developed cataracts that eventually resulted in blindness, but she still continued a rigorous schedule of meditating and receiving visitors interested in the Dhamma. She passed away quietly in 1978 after entrusting the center to a committee she appointed from among its members. Her younger sister, Upsik Wan, who up to that point had played a major role as a supporter and facilitator for the center, joined the community within a few months of Upsik Kees death and soon became its leader, a position she held until her own death in 1993. Now the center is once again being run by committee and has grown to accommodate sixty members.

A NOTE ON THE TRANSLATIONS

With two exceptions, the passages translated here are taken from Upsik Kees extemporaneous talks. The first exception is the prologue, excerpted from a poem she wrote on the twentieth anniversary of the founding of the center at Khao Suan Luang, in which she reflects on life at the center in its early years. The second exception is the first piece, The Practice in Brief, a brief outline of the practice that she wrote as an introduction to one of her early volumes of talks.

With two other exceptions, all of the passages are translated directly from the Thai. Many have previously appeared in books privately printed in Thailand or published by the Buddhist Publication Society in Sri Lanka. One book of her talksprinted under the titles

Next page

Upsik Kee Nanayon, also known by her pen name, K. Khao-suan-luang, was the foremost woman Dhamma teacher in twentieth-century Thailand. Born in 1901 to a Chinese merchant family in Rajburi, a town to the west of Bangkok, she was the eldest of five childrenor, counting her fathers children by a second wife, the eldest of eight. Her mother was a religious woman and taught her the rudiments of Buddhist practice, such as nightly chants and the observance of the precepts, from an early age. In later life she described how, at the age of six, she became so filled with fear and loathing at the miseries her mother went through during the pregnancy and birth of one of Kees younger siblings that, on seeing the newborn child for the first timesleeping quietly, a little red thing with black, black hairshe ran away from home for three days. This experience, plus the anguish she must have felt when her parents separated, probably lay behind her decision, made when she was still quite young, never to submit to what she saw as the slavery of marriage.

Upsik Kee Nanayon, also known by her pen name, K. Khao-suan-luang, was the foremost woman Dhamma teacher in twentieth-century Thailand. Born in 1901 to a Chinese merchant family in Rajburi, a town to the west of Bangkok, she was the eldest of five childrenor, counting her fathers children by a second wife, the eldest of eight. Her mother was a religious woman and taught her the rudiments of Buddhist practice, such as nightly chants and the observance of the precepts, from an early age. In later life she described how, at the age of six, she became so filled with fear and loathing at the miseries her mother went through during the pregnancy and birth of one of Kees younger siblings that, on seeing the newborn child for the first timesleeping quietly, a little red thing with black, black hairshe ran away from home for three days. This experience, plus the anguish she must have felt when her parents separated, probably lay behind her decision, made when she was still quite young, never to submit to what she saw as the slavery of marriage.