At several points I draw from short articles and bits and pieces from longer essays that I have published over the last decade; these are acknowledged in footnotes. I also make use of ideas presented in my 201314 Parchman Lectures at Baylor Universitys Truett Theological Seminary at several points. In chapters 13 and 14 I touch on matters that I explored in more detail in my 201516 Kent Mathews Lectures at Denver Seminary.

The Label Question

When I was thinking about an appropriate title for this book, I was tempted to take my cue from the late singer Prince, who in 1993 decided he no longer wanted to be called Prince. Indeed, he said, he no longer wanted to be known by any name at all. The folks who arranged his concerts did not like that idea, and after trying out several nameswith suggestions from Princes fansthe singer agreed to this one: The Artist Formerly Known as Prince.

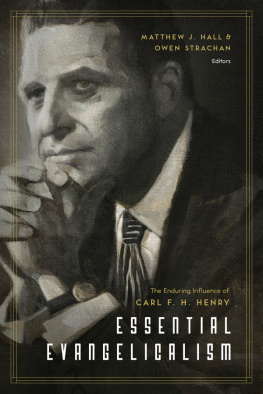

All of this came to mind as I was contemplating different word choices to sum up what this book is about. From the beginnings of my adult career as a teacher-scholar I have identified closely with American evangelicalism. Not that I have always been comfortable with everything associated with that label, but my discomfort has never been strong enough to make me want to move to other spiritual-theological environs. My original plan for this book was to highlight both the discomfort and the commitment by using the phrase restless evangelical in the title.

During the time that I have been writing this book, however, there has been considerable debate about whether evangelical is still a useful label. I wont go into the details that have given rise to this debate, except to say that for a variety of reasons evangelical has come to be seen by many as referring to a highly politicized form of Christianity here in North America.

I dont think the debate is a silly one. My own discomfort with identifying as an evangelical has certainly increased in the past few years. And some folks whom I have known and admired in the evangelical movement have said publicly that they can no longer own the label. I have taken their concerns seriouslywhich is why I thought of this Prince-inspired title: The Movement Formerly Known as Evangelicalism.

I think it will be clear to the readers of this book why I am not ready, though, to join the formerly known as movement. I still think the label stands for something wonderfully important, and I am not ready to give the label over to those who advocate an angry Religious Right politics. I will explain at a couple of points in these pages why I personally still hold on to the label.

Butand this is important for me to emphasize at the beginningI do not want the legitimacy of what I will be discussing in these pages to depend on the continued viability of the label. Suppose that ten years from now evangelical no longer means what it has in the past, as applied to a distinct movement within global Christianity. I hope the distinctives that the label once stood for will still be widely accepted. While I will be discussing here the reasons why I personally continue to find evangelical a viable descriptor, then, what I really care about is that the folks who are gravitating toward a formerly known as identity will still hold on to what has been the distinct spiritual and theological legacy of evangelicalism.

Like so many of my friends, I have no desire to be associated with the politicized excesses of present-day evangelicalism. But there is much in what many of us have loved in the evangelicalism of the past that weunder whatever label we choose to describe ourselves from here onshould not abandon.

I dont want to come off as defensive about my own preference for holding on to the label. I think it is a healthy thing to argue about whether a label like evangelical has outlived its usefulness. Indeed, for most of my life as an evangelical I have been engaged in conversationssome of them extended argumentsabout what it means to be an evangelical. Those have been important exercises for me. So, while not wanting to turn this book into an extended defense for keeping the label, I do want to explain at the outset some of my reasons for hoping that we do not abandon that way of describing ourselves. Then I will add some more reasons, briefly, at the end of this book.

Holding On to the Label

The Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals was established at Wheaton College in 1982, and it ended its existence in 2014. But while it lasted it was a wonderful gathering place for evangelical scholarly discussion. The historians Mark Noll and Nathan Hatch were the founders, and they had a knack for bringing interesting people together to explore fascinating topics. In the early years we often argued quite a bit about the evangelical label itself. Someone would come up with a proposal about what makes for being an evangelical, and someone else would respond that there were a lot of Catholics who fit the description. So we would go back to the drawing board.

In 1989 a British evangelical historian, David Bebbington, published a book in which he proposed a four-part definition of evangelical, and his account pretty much put an end to the

Of course, plenty of Christians who do not self-identify as evangelicals can claim each of those features. And some can even hold all four of them together. What strikes me as distinctively evangelical about the four features of the quadrilateral is, first of all, that these items are singled out as key theological basics, and second, that they are held in a certain way.