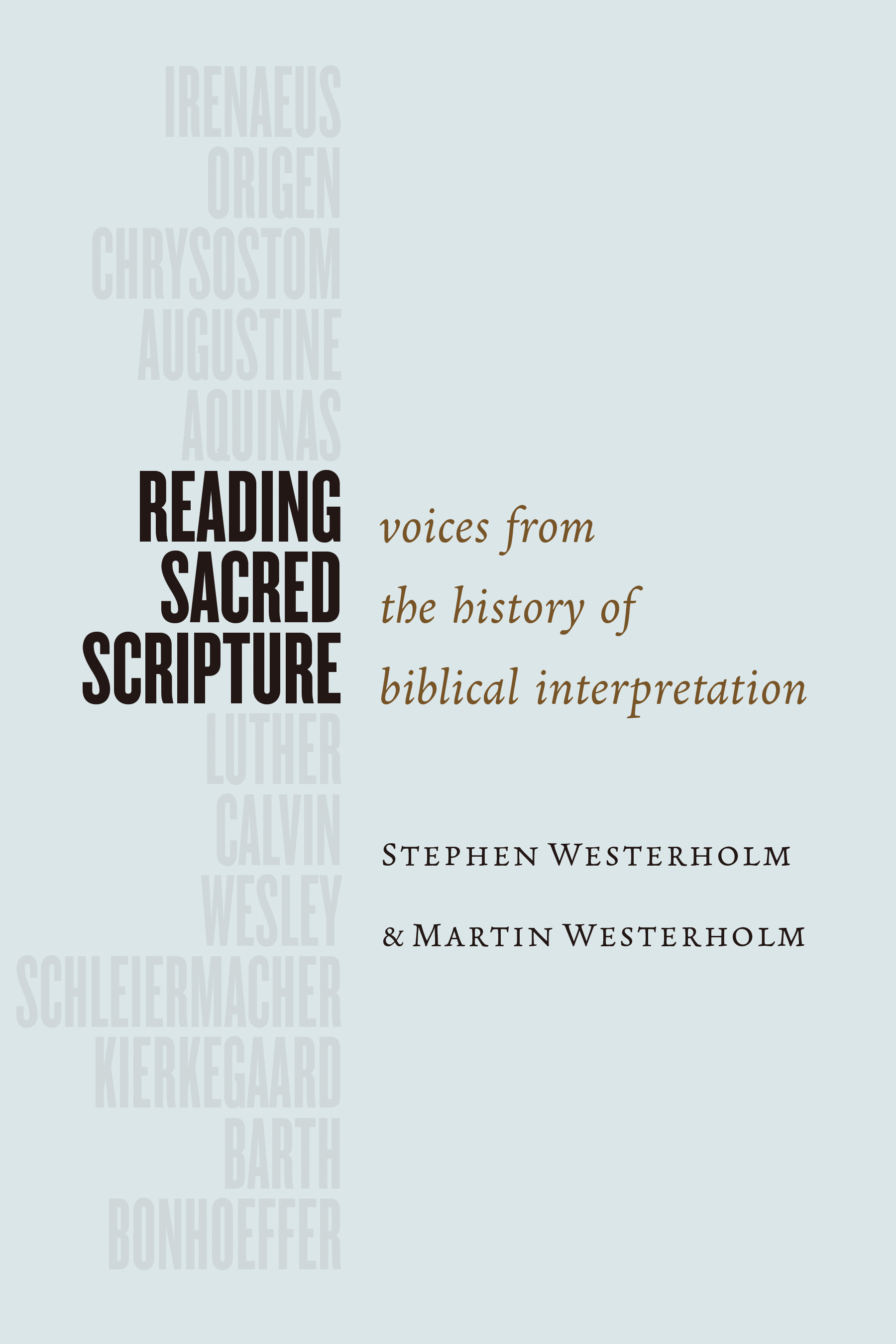

Reading Sacred Scripture

Voices from the History

of Biblical Interpretation

Stephen Westerholm & Martin Westerholm

William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company

Grand Rapids, Michigan / Cambridge, U.K.

2016 Stephen Westerholm and Martin Westerholm

All rights reserved

Published 2016 by

Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

2140 Oak Industrial Drive N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49505 /

P.O. Box 163, Cambridge CB3 9PU U.K.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Westerholm, Stephen, 1949

Reading sacred scripture: voices from the history of biblical interpretation /

Stephen Westerholm & Martin Westerholm.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8028-7229-6 (pbk.: alk. paper)

eISBN 978-1-4674-4551-1 (ePub)

eISBN 978-1-4674-4504-7 (Kindle)

1. Bible Criticism, interpretation, etc. History.

I. Title.

BS500.W445 2016

220.6 dc23

2015034463

www.eerdmans.com

For Paul and Jill

Contents

Some years ago, in reviewing a book with an enormous bibliography, the eminent New Testament scholar C. K. Barrett subtly suggested that the author might have been better served by wrestling with the relatively few books that are really important. His point is surely well taken. We should all be grateful for reference works that introduce dozens, or even hundreds, of figures in the history of biblical interpretation; as need arises, we consult them. The authors of the present work, however, have adopted Barretts proposed approach, inviting readers to engage seriously in the study of a mere dozen of the more important interpreters of Christian Scripture, from the second century to the twentieth.

No dozen figures, however significant, can adequately represent the history of biblical interpretation or exhaust the approaches that have been taken to reading the sacred text; nor would any two informed readers think the same twelve figures most worthy of consideration. But selections have to be made, and no informed reader will doubt the importance of each of the interpreters treated here. The present project was begun by Stephen, who intended to write on ten figures until he was told by a colleague that, however selective his undertaking, he could not omit Barth. That made sense, of course; but it also made sense, for one daunted by the prospect of tackling the Church Dogmatics, to invite the collaboration of Martin, who at the time was working intensively on Barth. Once on board, Martin agreed to treat Schleiermacher as well; the pairing with Barth is a natural one, given the way the latter used Schleiermacher as a foil for his own theology. But Schleiermacher merits study in his own right as one who profoundly influenced later Protestant thought.

Our project is clearly distinct from the several histories of critical scholarship on the Bible that have little or nothing to say on how the Bible was read prior to the seventeenth (or even the eighteenth) century. That story privileges those who programmatically read the Bible like any other book. The interpreters here portrayed, though by no means uniform in their approaches, all insist that the Bible is like no other book, and must be read accordingly. That, too, is a story worth telling indeed, one that, exhaustively told, would encompass many millions of readers more than the other. We stopped at twelve.

It remains only to repeat what Gunilla Westerholm (Stephens wife, Martins mother) is wont to say to dinner guests: Var s goda! (in the vulgar tongue, roughly, Dig in!).

. Barrett, Review, 114.

. Cf. Jowett, Interpretation, 377.

Among the slogans that set the agenda for much modern study of the Bible, the prescription that it should be read like any other book seems to me singularly unhelpful. We do not read Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves or Have It Your Way, Charlie Brown the same way we read Hamlet or King Lear. Critique of Pure Reason and The House at Pooh Corner are both, I believe, eminently worth reading (though, in the one instance, I am relying on others assurances), but they call for rather different approaches. Textbook of Medical Oncology requires yet another. To cut short a game becoming more fun by the minute, we may well ask: Like which other book are we supposed to read the Bible?

To be sure, these and other books can all be read the same way if we approach each with a particular question in mind: How frequently does the author split infinitives, dangle participles, or quote Russian proverbs? Or, what do Romeo and Juliet, Concluding Unscientific Postscript, and Pippi Longstocking tell us about eating habits at the time of their composition? (This game, too, could be fun.) These are, I suppose, legitimate questions doctoral dissertations have certainly been written on stranger topics but they seem somewhat limiting. Classic literature William Shakespeare, Sren Kierkegaard, Astrid Lindgren has more to offer its readers; those open to experiencing the more soon learn that different books make different demands on their readers.

Unless, then, we are reading the Bible merely to carry out our own limiting agendas, the notion that it should be read like any other book will be true only in the sense that the Bible, like any other book, calls for a particular kind of reading. Sensitive readers of the Bible, like sensitive readers of any text, will be alert to what is being asked of them, given the nature of the text before them; it is then, of course, up to their discretion

The Letters of Paul

Pauls Mission and Mandate

When the apostle Paul wrote his first epistle, scarcely twenty years had passed since the central events of his message and that of the other apostles had taken place (cf. 1 Cor. 15:3-11). His last letters were composed little more than a decade later. At that point, the gospel he brought to Gentiles was not only good news, but fresh.

But Pauls depictions of a desperate plight merely set the stage for news of its stunning transformation: though human wickedness abundantly warrants the outpouring of Gods wrath, the Son of God brings deliverance to all who trust in him (1 Thess. 1:10; 5:1-11); though the whole world is culpable before God, God has intervened to put things right, and to declare sinners righteous, through the redemption he has provided in Christ Jesus (Rom. 3:19-24). God demonstrates his love for us in that, while we were still sinners, Christ died for us.... When we were enemies, we were reconciled to God by the death of his Son (Rom. 5:8, 10).

Clearly, for Paul, the transformation of the human condition required, and was brought about by, divine intervention:

[T]here is a new creation; the old has passed away; look, the new has come into being! All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ, and gave us the ministry of reconciliation; that is, in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them; and he has committed to us the message of reconciliation. (2 Cor. 5:17-19)

Yet, as the same quotation makes clear, divine intervention extended beyond the recent work of Christ (through whom God reconcile[d] the world to himself) to include the commissioning of Paul (and the other apostles) to convey to the world the message of reconciliation. Consciousness of a divine commission and a concomitant sense of accountability mark all of Pauls letters and undoubtedly lent conviction to his spoken message as well.

As we have been approved by God to be entrusted with the gospel, so we speak, not pleasing people, but pleasing God who tests our hearts. (1 Thess. 2:4)

If I proclaim the gospel, it is nothing I can boast about; for I am under an obligation, and woe to me if I do not proclaim the gospel! (1 Cor. 9:16; see also Rom. 1:5, 14-15; 1 Cor. 4:1-5; 15:15; 2 Cor. 2:17; 4:1; Gal. 1:1-12)