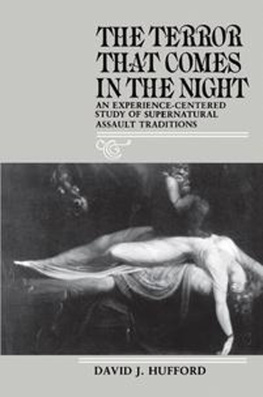

The Terror That Comes in the Night

Publications of the American Folklore Society

New Series

General Editor, Marta Weigle

Volume 7

The

Terror

That

Comes

in the

Night

An Experience-Centered Study of

Supernatural Assault Traditions

David J. Hufford

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia

This work was published with the support of the Haney Foundation.

Copyright 1982 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hufford, David

The terror that comes in the night

(Publications of the American Folklore Society; new ser., v. 7)

Includes Bibliography (p.) and index

ISBN 0-8122-7851-8 (cloth). ISBN 0-8122-1305-X (pbk)

1. Nightmares. 2. Incubi. 3. Witchcraft. 4. Sleep paralysis. I.

| Title. II. Series |

| BF 1099.N53H83 1982 398'.45 | 82-40350

CIP |

Contents

Acknowledgments

It is impossible to list all those who have helped with the research and writing of this book. In fact, I benefited from so much advice and direction before I had any notion of where the research was leading that I doubt that I myself am aware of all the major contributions. Nonetheless, certain invididuals stand out so clearly that I must give them a special word of thanks here.

First of all my family has been crucial in this work. Not only did they frequently have to relinquish my time, but my wife, Ellin, has from the beginning helped me enormously in library research, the location and organization of materials, checking and making suggestions on drafts, and countless other tasks without which the book would still be far from finished. And all of this took place in the context of being unable to give a concise and satisfactory answer when people asked, What is the book about? More than any other she has shared with me the odd feeling of working on a subject for which there is no really useful English vocabulary.

Among my teachers I am particularly grateful to Anthony Wallace and Don Yoder of the University of Pennsylvania for having first made clear to me the wonderful complexity and inherently fascinating nature of belief as a subject for study; and to Kenneth Goldstein of Penn for emphasizing the profound respect and seriousness that we owe to those whom we study. Also, though I never took a course from him and did not meet him until the latter part of my career as a folklore graduate student, I count Wayland Hand of UCLA as one of my teachers, and his interest and encouragement in all of my work with belief have been invaluable.

As the topic of the Old Hag began to resolve into a subject of study, the Folklore Department and the Folklore and Language Archive of Memorial University in Newfoundland provided the only setting in which that study could have been started. Of the many friends and colleagues at Memorial who helped me with the work in its beginning stages I am especially indebted to Neil Rosenberg and Herbert and Letty Halpert for advice and suggestions. After research on the mainland had raised new questions about the Newfoundland beliefs and accounts, they continued to help by making the archive available to me for further investigation.

Help in the form of access to archival material has also been given to me by William (Bert) Wilson at the University of Utah (Logan) and Lynwood Montell at Western Kentucky University. Wayland Hand has also helped enormously in this regard by making his Dictionary of American Popular Beliefs and Superstitions files available to me. And in the use of those files Waylands able assistants, Frances Tally and Sondra Theiderman, helped me repeatedly and continued to send me useful additional references after my visits to the files at UCLA.

Jan Brunvand (University of Utah), Roger Welsch (University of Nebraska), and Michael Taft (University of Saskatchewan) have also kept my research in mind and have not only offered encouragement but have sent me numerous references and copies of useful unpublished material.

At the Penn State College of Medicine my colleague Robert Miller has provided endless help and encouragement by reading drafts, sending a constant stream of pertinent references, and taking a great deal of time to discuss difficult points ranging from the analysis of data to the selection of appropriate vocabulary for use in this book. Finding such interest and enthusiasm, coupled with the distinctly different academic perspective of medical sociology, has been invaluable. Also at the College Arthur Zucker has been very helpful and encouraging as I have struggled with the philosophy of science issues raised by this research.

Of course the cooperation of those whom I have interviewed about their experiences has been essential. Without their willingness to take this time, and to discuss personal experiences which in many cases they had never before mentioned to anyone, this book could not have been written. They have been most generous with both their time and their trust.

To all of these people, and to all of those whose aid I have not been able to mention, I am very grateful. I hope that in this book they will find their support in some measure rewarded.

Introduction

No commonly accepted term exists in modern English for the experience that is the subject of this book. This unusual situation of language is an object of, as well as a complication in, my research. The use of such folk terms as incubus, nightmare, and witch riding, for example, has led to mistaken conclusions about the distribution of the experience that lies behind the associated beliefs. Such problems in terminology have made it necessary to investigate the academic study of belief along with the beliefs themselves. In the absence of a precise name, I have chosen a title for this book that conveys the feeling characteristic of what some have considered to be the most frightening event ever experienced by humansthe terror that comes in the night.

When I began this project I expected it to take only a few months and to result in a single article.that the investigation is complete even now. One reason is that the topic has proved to be much larger than I could have known in the beginning. Another reason is that my subject matter has required the development of a novel approach, a fact that I came to realize gradually in the course of the work. Only when I had completed this book did I begin to see the outlines of what I now call the experience-centered approach to the study of supernatural belief. The study presented here does, however, permit a view of some of the major emphases and characteristics of the approach, and some comments about these may make the implications of the book as a whole easier to grasp. I present this approach as one that can be added to those already in use. I do not propose that it should become the only way that folklorists should study belief or that it should replace any specific alternatives, although I do believe that it can substantially supplement many other strategies.

This approach recognizes the epistemological difficulties of focusing on experience, especially when dealing with the materials of greatest interest in the folkloristic study of supernatural belief. Anothers experience is always a reconstruction to be inferred rather than a fact to be directly observed. The data the folklorist relies on for this reconstruction consist largely of verbal accounts, and these are well known to be loaded with sources of error: faulty memories; the creative processes of oral tradition; the very processes of perception, which are generally recognized to be influenced by expectation. But the folklorist cannot consider such factors to be merely sources of error, for they are themselves important subjects of study, and the changed material is recognized as having its own integrity and authenticity. Some folklorists have gone so far as to say that in the study of supernatural belief the issue of whether a given belief is correct is irrelevant.