For Katharine, Nathan, Max and Holly-Rose

Contents

Writing the early-modern history of Youghal was a difficult but hugely rewarding experience. It would not have been possible without the support of several people. I am very grateful for the education, inspiration and support I received from the history department at University College Cork, in particular from Prof. Jennifer OReilly, Dr Diarmuid Scully, Dr Hiram Morgan and Dr Andrew McCarthy. My research was enhanced with conversations with David Kelly whose knowledge and enthusiasm of, and for, the subject were invaluable and whose work on an Atlas of Youghal will have a far-reaching influence on future generations researching the history of the town. I received generous support and advice from writers, whose works were a constant reference point, my thanks to Prof. Nicholas Canny, Dr Michel Siochr and Dr Peter Elmer for their willing correspondence. I am eternally grateful to Ronan Colgan of The History Press Ireland for his initial interest in the subject. Many thanks are due to my son, Nathan for enhancing the book with his arresting illustrations and to my close friends Louise and Conor Hegarty for their interest and for reading a draft of part of the book, affording it very helpful comments. My primary gratitude and debt is to my wife, Katharine whose perpetual encouragement seems to me an endless upward spiral of inspiration; the reading, conversations and support were the foundation, continuance and completion of the work.

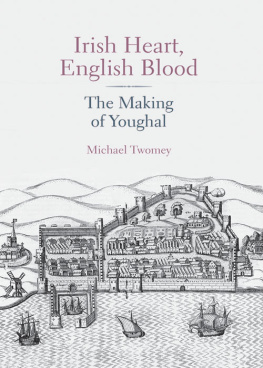

The map of Youghal on the front of this book was drawn in the 1630s, having been commissioned by former President of Munster, Sir George Carew. The original drawing, with its precise lines and neat composition, is the construct of a propaganda-driven desire to suppress the fluid nature of reality. In effect, the map is a lie. Its very cleanliness betrays a murkier design. Yet, the DNA that makes up all propaganda contains a necessary strain of truth, no matter how fragile in this case, to make it believable. This illustration is an impression of the town of Youghal in the 1630s and there is much in the image that represents the reality of early modern Youghal; it was indeed, a walled seaport town. The purpose of creating this image was to promote the idea of Youghals progress, its security and its wealth. It represents the success of Youghals assimilation into English manners, culture and design. The image is boastful, the towns seemingly indestructible walls protecting those inside. It also invites those outside, such as merchants, adventurers in Ireland and England, as well as government officials, to muse over the great possibilities the town has to offer them. It was created at a time of high confidence in the belief that the English plantation programmes in Munster had yielded a sort of self-contained Eutopia, a minor jewel, but a jewel nonetheless, in the English Crown. This image has endured over other images and drawings of Youghal, drawings that are far less sterile. Like the story of Walter Raleigh planting the first potato in Ireland at his residence in the town, the image of this map has seeped into the public consciousness and solidified therein as historical fact.

The early modern history of Youghal from the mid-1500s to the mid-1600s is not as neat and clean as the map illustrates. Complex, never anything less than extraordinary, bloody and equally industrious, it is a history of survival, blind ambition and feats and failures from individual as well as national entities. It is also the history of the troubled relationship between Ireland and England. The ebb and flow of cultural assimilation, colonisation and resistance created a volcanic landscape of political and religious tension out of which the town grew to prominence. Populating this volatile and smouldering environment was a host of irrepressible characters and peoples whose stories reveal the unpredictable nature of the early modern period. Irish Heart, English Blood is an attempt to make sense of the social, political and religious tumult that erupted from these dynamics. For almost a century the town of Youghal acted as the theatre that housed the IrelandEngland power play. Its history is imbued with shame and sadness, terror and triumph. I believe that in the years between the 1579 Munster rebellion and the witch trial of 1661, in the aftermath of the Restoration of Charles II, Youghal witnessed an unparalleled history that shaped its future for the next 300 years in a way that no history of the town had done before or has done since.

I have attempted to view this period of history through some of the main figures who played a significant role in the towns formation, such as Gerald Fitzgerald, Walter Raleigh, Edmund Spenser, Richard and Roger Boyle, Murrough OBrien, Oliver Cromwell and others. All of these mens lives have been written about extensively elsewhere and while there are some narrative themes that are inevitably touched upon, the focus for this book is their direct involvement in, or effect on, the history of Youghal. Therefore, some general points of national or international historical interest are used only as frameworks to support the primary purpose of the book to understand how Youghal was affected by the extraordinary events of the times and what role it played in them.

This is not the first history written about early modern Youghal. The most well-known document is Samuel Haymans The New Hand-book for Youghal , which combines an ecclesiastical history of the religious buildings in and around Youghal with records taken from the Annals of the Four Masters . Haymans content is valuable for research in these particular areas. The other significant and somewhat superior record is Richard Caulfields The Council Book of the Corporation of Youghal . This monumental volume of Corporation records from 1610 to 1800 is complemented by the Annals of Youghal , including various letters and correspondences. Without Caulfields Trojan work, this book would not have been possible, nor would many other works about Youghal. Caulfields history comes closest to helping us understand the everyday life of the town. Details of the towns social and political workings provide the reader with an insight into the life of the early modern citizen, what the town might have been like in times of war and in times of peace. While Caulfields collection of documents lacks a cohesive narrative to stitch them together, Haymans history is full of romance, is unapologetically religious and desires to delight the reader as well as inform. Local modern writers, documentarians and historians relating the histories of Youghal have tended to draw more from the Hayman style of historiography with its emphasis on mixing facts with myths and legends. These works, from a plethora of journals, articles, pamphlets and so on, also rely on Caulfield. All of these works offer varying degrees of insight. And while they tend to include a cross-section of differing periods of history from ancient to medieval, modern and early modern they possess value in what might be termed fascinating history and fun facts in heritage stories and have, to their great credit, driven a local history revival in recent years. This book attempts to bring together the social, religious and political history of the early modern period only and without the myths and legends, in some cases arguing against them.

Irish Heart, English Blood is the first book since Hayman and Caulfield to relate the history of Youghals involvement as a significant player in the relations between Ireland and England in the early modern period. I have tried to write the narrative of the towns history in a way that has not been done before. To achieve this, and a better understanding of how Youghal came into being, I have relied mostly on Caulfields collection of documents, Irish and British national archives as well as historians writings on political explorations of the period and studies on the central historical characters. I have also relied on academic journals and articles on various topics from economics and religion to society at large.

Next page