Title page

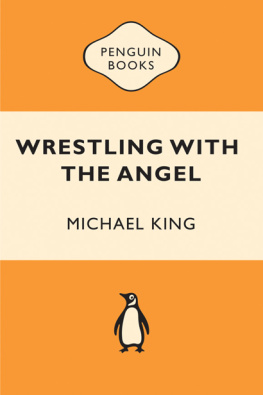

Wrestling With God

The Story of my Life

Lloyd Geering

imprint-academic.com

Copyright page

2013 digital version by Andrews UK Limited

www.andrewsuk.com

Copyright Lloyd Geering, 2006

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

No part of any contribution may be reproduced in any form without permission, except for the quotation of brief passages in criticism and discussion.

First published in New Zealand, 2006, by Bridget Williams Books Limited, PO Box 5482, Wellington, in association with Craig Potton Publishing Limited, PO Box 555, Nelson.

Originally published in the UK, 2007, by

Imprint Academic, PO Box 200, Exeter EX5 5YX, UK

Originally published in the USA, 2007, by

Imprint Academic, Philosophy Documentation Center

PO Box 7147, Charlottesville, VA 22906-7147, USA

Front cover image:

Jacob Wrestling with the Angel (detail)

by Cambiazo Corbis Corporation

Back cover photograph Neil Pardington

Dedication

To Shirley

Quotation

Jacob was left alone; and some one wrestled in the dust with him until the breaking of day. When he saw that he had not won the victory over Jacob, he struck him on his hip socket so that Jacobs hip was dislocated in the struggle. Then the man said, Release me for the dawn has come up. But Jacob said, I will not release you unless you bless me. So the man said to him, What is your name? and he replied, Jacob! Then he said, No longer shall Jacob be the name by which you are called, but Israel, for you have persevered with God and with men, and you have won the victory. Then Jacob questioned him and said, Please tell me your name. But he said, Why is it that you ask for my name? So then and there he blessed Jacob. Then Jacob called the name of that place Peniel, For I have seen God face to face, yet my life has been preserved.

Genesis 32.2430

In Hebrew there is linguistic similarity between Israel and persevere, and between Peniel and the face of God.

Preface

Why write an autobiography when its publication can be so readily interpreted as an exercise in self-promotion? It might be argued that, in my case, it marks an attempt to set the record straight after my involvement in a cause clbre forty years ago one that resulted in a variety of conflicting images preceding me wherever I went. Yet how could that perhaps justifiable aim be achieved when an autobiography is of necessity subjective and hence biased? On the other hand, since no two portraits of a person (whether literary or graphic) present quite the same image, biography is never as objective as one might think. Indeed, over the years many brief profiles of me have appeared in the press, a few of them so warped that they simply added to the confusion.

In former times, such a state of affairs might have inclined one to say that the real inner self is known only to God. But in this secular age that would be tantamount to conceding that no one can know the inner self. And that in turn raises the question of whether there is an inner self apart, that is, from the impressions one has of ones self, together with the personas perceived by others. The Buddhist tradition began to struggle with that issue two and a half thousand years ago.

It is my hope that those who read this book will come to recognise that the real reason for writing it is not personal but theological. I am endeavouring to describe how my thinking about religion in general and God in particular has changed and developed over the years by setting this evolutionary process in the context of the chief influences and events in my life that have helped to shape it. This book is, if you like, a theological diary, written retrospectively.

When writing Every Moment Must be Lived , the story of my late wife Elaine, I noted that I had tried to keep myself out of that portrait as far as possible. But because our lives had been intertwined for over fifty years, it was inevitable that her story would also contain part of my own. The two or three hundred people who have read Elaines story may observe a few overlaps, but for the most part I have narrated those sections a little differently here.

In the present task I have been indebted to a number of people, three of whom in particular I must acknowledge here, for their contributions now lie hidden within these pages. I am grateful to my friends Tom Hall of Foster, Rhode Island (a skilful wordsmith) and Allan Davidson of St Johns College, Auckland (a probing church historian): they both read the initial draft, chapter by chapter, and made many valuable suggestions, nearly all of which have been included. I am also grateful for the continuing encouragement of Bridget Williams, for this is now the fifth of my books she has published.

Lloyd Geering

Wellington, July 2006

1: Who Am I?

People sometimes say that they are trying to find out who they are. Since this expression was never heard when I was young, I suspect its current use reflects the increasing awareness of the absence of the traditional certainties that once taught people from childhood just who they were and where they stood in society. In the Christendom of the past, people were shaped by the Christian view of reality in which God had a plan for the world and for everyone in it. Since for the most part this conviction enabled people to face life with some degree of confidence and equanimity, they had no need to ask who they were.

In todays more secular society we enjoy much more freedom, both in choosing a career and developing our individuality. This breadth of choice means that we have more responsibility for the kind of person we become, but the erosion of traditional certainties leaves us more vulnerable when we encounter lifes many perplexities. Increasingly, it seems, even middle-aged people set out quite consciously on a spiritual quest for ultimate meaning or purpose in life. It is in such circumstances that they say they want to discover who they really are, for having a sense of personal identity and finding a purpose in life are closely correlated.

It was almost universally assumed in our cultural past (and still believed by many today) that ones essential self is a spiritual or non-physical entity a soul that can exist quite independently of the physical body in which it temporarily resides. The presence of this belief in Christian culture reflects the enduring influence of Plato, who indeed regarded the physical body as a kind of prison from which the soul seeks to be free. If there were such an entity as an immortal human soul, separable from the body, it would be logical to conclude (as Plato himself did) that the soul not only survives the death of the body, but also had some sort of prior existence. In his essay Dream Children, Charles Lamb mused upon such a possibility. But early Christian thinkers never entertained this notion in the same way as they adopted the Platonic view that the soul survives death.

In modern times this view of the self as an immortal soul has been slowly eroding, mostly because the human sciences have helped us to understand the essential relationship of the self-conscious mind with the brain and central nervous system. Even before that, the Scottish philosopher David Hume, in his essay On the Immortality of the Soul, had drawn attention to the obvious correlation between soul and body: he observed that in infancy they are both immature; they grow to maturity in tandem; and in old age they show equal signs of decay. Increasingly, therefore, we have ceased to understand the self in terms of the concept of an immortal human soul, but rather acknowledge ourselves to be psychosomatic organisms. This means that the self (or soul) comes to an end when the body dies; we humans live a finite existence between conception and death, just like all the other innumerable forms of planetary life. If any part of us outlasts death (though without quite attaining immortality), it is to be found in our genes. These we inherit from our ancestors and pass on to our progeny; and most of them we have in common with the other higher animals.

Next page