How has the church come to believe what belongs in the Bible and what does not belong?

STATEMENT OF BELIEF

The church has historically believed that a specific set of writings called the canon of Scripturecomposes the Old and New Testaments. This list of divinely inspired and authoritative narratives, prophecies, gospels, letters, and other writings that make up the Word of God developed in the early church. The canon of the Protestant church differs from that of the Roman Catholic Church. The Protestant canon is composed of sixty-six books, while the Catholic canon is more extensive. It includes the Apocrypha, extra books in the Old Testament (e.g., Tobit, Judith), and additions to certain Old Testament writings as found in the Protestant Bible (e.g., additions to Esther, Bell and the Dragon). Evangelical churches follow the Protestant canon.

THE CANON IN THE EARLY CHURCH

From its beginning on the day of Pentecost, the church considered the Hebrew Bible to be the Word of God (2 Tim. 3:1617; 2 Peter 1:1921). The writings that composed the Jewish Scripturesnow called the Old Testamentwere fixed and had been so for several centuries prior to the coming of Jesus Christ. The eminent Jewish historian Josephus (AD 37100) noted: From Artaxerxes [464423 BC] to our own time the complete history has been written, but has not been deemed worthy of equal credit with the earlier records, because of the failure of the exact succession of the prophets.of the authoritative Word of God. Indeed, the canon of the Jewish Scriptures had come to a close at the time of the writing of Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther (435 BC). No other writings had been nor could have been added to the Hebrew Bible in the intervening period, because divine inspiration of the prophets had ceased.

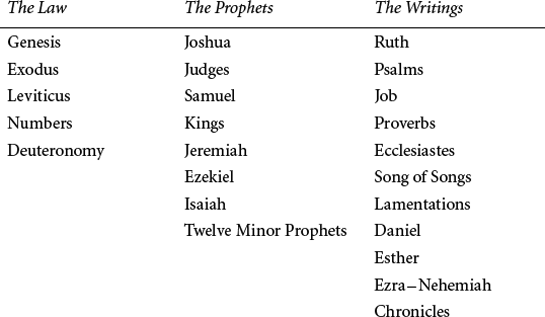

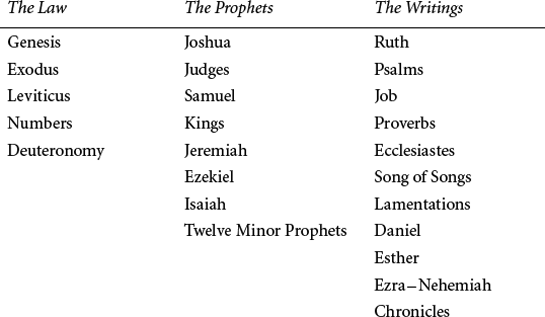

What did the Hebrew Bible look like? Josephus noted twenty-two divinely inspired books in the Hebrew canon: the five books of Moses, thirteen prophetic books, and four books containing hymns and precepts.

This Hebrew Bible, with its fixed canon, was the Bible of the early church.todays church is familiar, all of the books that we consider to be canonical were present and together composed the Word of God for the Jewish peopleand the early church.

Following the death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ, together with the outpouring of the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost to initiate the church, a new phase of revelation began. While relying on the authority of the divinely inspired Hebrew Scriptures, the church was conscious of being the recipient of new truth concerning the person and work of Jesus Christ and the Christian mission in the world.

The ultimate source of this truth was God himself. Justin Martyr resolutely affirmed, For I choose to follow not men or mens doctrines, but God and the doctrines [delivered] by him.

Not everyone agreed with this harmony, however. Beginning in the second century, heretics emphasized an apparent conflict between the prophets and the new Christian truth. To counter this, the apologists (Christian writers who defended the faith) underscored the unity of the prophetic and apostolic revelation. Tertullian, speaking of the church, noted: The law and the prophets she unites in one volume with the writings of the evangelists and apostles; from which she drinks in [receives] her faith.

Our discussion may give the wrong impression that the early church possessed a written Bible readily available to all its members (much like each of us taking our own copy of the Bible to church and Bible study). This, however, was not the case. Indeed, for the first few decades of its existence, the church had only oral stories that it could pass on. Even when the last writings of what was to become the New Testament were being penned, the church was still largely dependent on unwritten tradition, which continued for the first several centuries of the church.

These written records and unwritten tradition were seen as two parts of a unified whole, and the early church appealed to both to express its doctrine and to fight heresy. The only true and life-giving faith, which the church has received from the apostles and imparted to her sons, Moreover, this rule of faith was public knowledge, accessible to everyone. Thus, it stood in contrast to certain heresies that claimed a secret knowledge of the truths of the Christian faith. This hidden wisdom was reserved for the elite of these erring movements and often went against biblical teaching. Not so for apostolic tradition: It was public knowledge in conformity with Scripture.

The recipients and transmitters of this tradition were, in particular, the successors of the apostles, the bishops who led the churches. They were the guarantee that what was believed and practiced by the churches was in accord with this apostolic rule of faith. These bishops were not a source of new revelation that stood alongside of written Scripture. They were, instead, faithful transmitters of the truth received from the apostles and ultimately from God himself. Tertullian held that all doctrine which agrees with the apostolic churchesthose molds and original sources of the faithmust be reckoned for truth, as undoubtedly containing that which the churches received from the apostles, the apostles from Christ, and Christ from God.

Eventually, some of this apostolic tradition was written down. In this way the gospel has come down to us, which [the apostles] did at one time proclaim in public, and, at a later period, by the will of God, handed down to us in the Scriptures, to be the ground and pillar of our faith.

To the collection of authoritative Hebrew Scripture were eventually added some additional writings in the form of gospels, a historical account, letters, and an apocalypse (a revelation of future events). Some of these writings themselves pointed to an expansion of the canon of Scripture. For example, Peter spoke of the letters of the apostle Paul in the context of the other Scriptures (2 Peter 3:1416), and Paul himself connected a saying of Jesus (The laborer is worthy of his wages) with Deuteronomy 25:4, referring to both as Scripture (1 Tim. 5:18).

The earliest Christian writings outside of our New Testament continued this practice of elevating the words of Jesus and the writings of the apostles, recognizing in them the authority of divine revelation. One example was a reference by Polycarp to a portion of Pauls letter to the Ephesians (4:26) as Scripture.

A crucial question arose: Which of the writings from the early church should be included in this expanding canonconsisting of both the Hebrew Bible (our Old Testament) and the New Testament? (Irenaeus was the first to call the two parts of this collection the Old and New Testaments.) The letters of Paul, written by an apostle clearly invested with divine authority, were easily recognized as belonging to canonical Scripture. But what about the anonymous letter to the Hebrews? Why should Mark and Luke be placed alongside the gospels written by the apostles Matthew and John? And what about the Letter of Barnabas