R.G. Collingwood - Religion and Philosophy

Here you can read online R.G. Collingwood - Religion and Philosophy full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: Barnes & Noble, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Religion and Philosophy

- Author:

- Publisher:Barnes & Noble

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Religion and Philosophy: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Religion and Philosophy" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

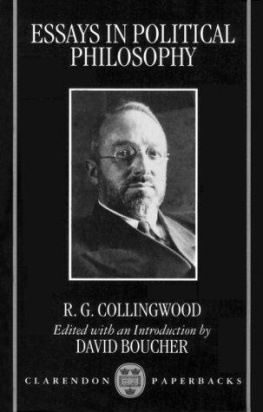

Early 20th century historian and philosopher R.G. Collingwood contends here that religion and philosophy are more closely intertwined than previously assumed. Arguing that the minds workings can be decoded only by self-analysis, and not by scientific methods, Collingwood identifies the characteristics of religion that make it resistant to traditional scientific investigation.

Religion and Philosophy — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Religion and Philosophy" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

R. G. COLLINGWOOD

This 2011 edition published by Barnes & Noble, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.

Barnes & Noble, Inc.

122 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10011

ISBN: 978-1-4114-3893-4

PREFACE

I T was my intention to write this book as an essay in philosophy, addressed in the first instance to philosophers. But the force of circumstances has to some extent modified that plan. To make of it an academic treatise, armed at all points against the criticism of the professed specialist, would require time far beyond the few years I have spent upon it. The claims of a "temporary" occupation, very different from that in which I began to write, leave no opportunity for the rewriting and careful revision which such a work demands, and I had set it aside to await a period of greater leisure. But the last year has seen a considerable output of books treating of religion from a philosophic or intellectual rather than either a dogmatic or a devotional point of view; and I believe that this activity corresponds to a widespread reawakening of interest in that aspect of religion among persons not specially trained in technical philosophy or theology. In the hope of making some small contribution to this movement, I venture to publish this book as it stands.

No one can be more conscious than myself of its shortcomings; that they are not far greater is largely due to the patience with which certain friends, especially E. F. Carritt, F. A. Cockin, and S. G. Scott have read and criticised in detail successive versions of the manuscript. It must not be supposed, however, that they are in agreement with all my views.

69 C HURCH S TREET , K ENSINGTON , W.

July 30, 1916.

INTRODUCTION

T HIS book is the result of an attempt to treat the Christian creed not as dogma but as a critical solution of a philosophical problem. Christianity, in other words, is approached as a philosophy, and its various doctrines are regarded as varying aspects of a single idea which, according to the language in which it is expressed, may be called a metaphysic, an ethic, or a theology.

This attempt has been made so often already that no apology is needed for making it again. Every modern philosophy has found in Christianity, consciously or unconsciously, the touchstone by which to test its power of explanation. And conversely, Christian theology has always required the help of current philosophy in stating and expounding its doctrines. It is only when philosophy is at a standstill that the rewriting of theology can, for a time, cease.

But before embarking on the main argument it seemed desirable to ask whether such an argument is really necessary: whether it is right to treat Christianity as a philosophy at all, or whether such a treatment, so far from being the right one, really misses the centre and heart of the matter. Is religion really a philosophy? May it not be that the philosophy which we find associated with Christianity (and the same applies to Buddhism or Mohammedanism) is not Christianity itself but an alien growth, the projection into religion of the philosophy of those who have tried to understand it?

According to this view, religion is itself no function of the intellect, and has nothing to do with philosophy. It is a matter of temperament, of imagination, of emotion, of conduct, of anything but thought. If this view is right, religion will still be a fit and necessary object of philosophic study; but that study will be placed on quite a different footing. For if Christianity is a philosophy, every Christian must be, within the limits of his power, a philosopher: by trying to understand he advances in religion, and by intellectual sloth his religion loses force and freshness. Above all, if Christianity is a philosophy, it makes a vital difference whether it is true; whether it is a philosophy which will stand criticism and can face other philosophies on the field of controversy.

On the other hand, if religion is a matter of temperament, then there are no Christian truths to state or to criticise: what the religious man must cultivate is not intellectual clearness, but simply his idiosyncrasy of temperament; and what he must avoid is not looseness of thought and carelessness of the truth, but anything which may dispel the charmed atmosphere of his devotions. If Christianity is a dream, the philosopher may indeed study it, but he must tread lightly and forbear to publish the results of his inquiry, lest he destroy the very thing he is studying. And for the plain religious man to philosophise on his own religion is suicide. How can the subtleties of temperament and atmosphere survive the white light of philosophical criticism?

It is clearly of the utmost importance to answer this question. If religion already partakes of the nature of philosophy, then to philosophise upon it is to advance in it, even if, as often happens, philosophy brings doubt in its train. He knows little of his own religion who fears losing his soul in order to find it. But if religion is not concerned with truth, then to learn the truth about religion, to philosophise upon it, is no part of a religious man's duties. It is a purely professional task, the work of the theologian or the philosopher.

These issues have been raised in the First Part of this book, and it may be well to anticipate in outline the conclusions there advanced.

In the first place, religion is undoubtedly an affair of the intellect, a philosophical activity. Its very centre and foundation is creed, and every creed is a view of the universe, a theory of man and the world, a theory of God. If we examine primitive religions, we shall find, as we should expect, that their views of the universe are primitive; but nonetheless they are views of the universe. They may be rudimentary philosophies, but they are philosophies.

Secondly, religion is not, as philosophy is generally supposed to be, an activity of the "mere" intellect. It involves not only belief but conduct, and conduct governed by ideals or moral conduct. Religion is a system of morality just as much as a system of philosophical doctrines. Here, again, systems vary: the savage expresses a savage morality in his religion, but it is a morality; the civilised man's religion, as he becomes more civilised, purges itself of savage elements and expresses ideals which are not yet revealed to the savage.

Thirdly, the creed of religion finds utterance not only in philosophy but in history. The beliefs of a Christian concern not only the eternal nature of God and man, but certain definite events in the past and the future. Are these a true part of religion at all? could not a man deny all the historical clauses in the Creed and still be in the deepest sense a perfect Christian? or be a true Moslem while denying that Mohammed ever lived? The answer given in Chapter III. is that no such distinction can be drawn. Philosophy and history, the eternal and the temporal, are not irrelevant to one another. It may be that certain historical beliefs have in the past been, or are now, considered essential to orthodoxy when in fact they are not, and are even untrue; but we cannot jump from this fact to the general statement that history is irrelevant to religion, any more than we can jump from the fact that certain metaphysical errors may have been taught as orthodox, to the statement that metaphysics and religion have nothing in common.

A fourth question that ought to be raised concerns the relation between religion and art. The metaphorical or poetical form which is so universal a characteristic of religious literature seems at first sight worlds removed from theology's prose or the "grey in grey" of philosophy. Is the distinction between religion and theology really that between poetry and prose, metaphorical and literal expression? And if so, which is the higher form and the most adequately expressive of the truth?

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Religion and Philosophy»

Look at similar books to Religion and Philosophy. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Religion and Philosophy and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.