Beacon Press

25 Beacon Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02108-2892

www.beacon.org

Beacon Press books

are published under the auspices of

the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations.

1975,1976 by Thich Nhat Hanh

Preface and English translation 1975,1976,1987

by Mobi Ho

Afterword 1976 by James Forest

Artwork 1987 by Vo-Dinh Mai

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

09 08 07 06 05 11 10 9 8 7

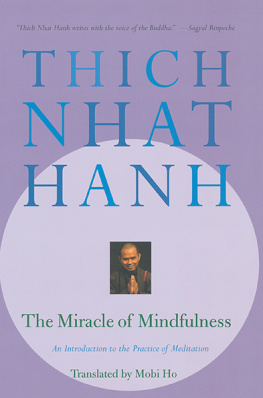

The Library of Congress catalogued the previous paperback edition as follows:

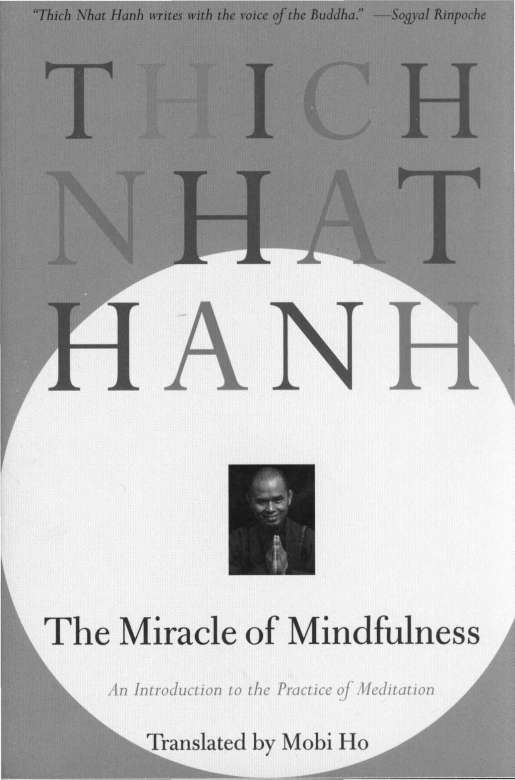

Nhat Hanh, Thich.

The miracle of mindfulness. Translation of Phep la cua su tinh thuc. ISBN 0-8070-1232-7 (cloth) ISBN 0-8070-1239-4 (paper) 1. Meditation (Buddhism) 2. Buddhist meditations. I. Title. BQ5618.V5N4813 1987 294.3'433 87-42582

Contents

Translator's Preface by Mobi Ho vii

One

The Essential Discipline 1

Two

The Miracle Is to Walk on Earth 11

Three

A Day of Mindfulness 27

Four

The Pebble 33

Five

One Is All, All Is One: The Five Aggregates 45

Six

The Almond Tree in Your Front Yard 55

Seven

Three Wondrous Answers 69

Exercises in Mindfulness 79

Nhat Hanh: Seeing with the Eyes of Compassion by James Forest 101

Selection of Buddhist Sutras 109

Translator's Preface

The Miracle of Mindfulness was originally written in Vietnamese as a long letter to Brother Quang, a main staff member of the School of Youth for Social Service in South Vietnam in 1974. Its author, the Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, had founded the School in the 1960s as an outgrowth of "engaged Buddhism." It drew young people deeply committed to acting in a spirit of compassion. Upon graduation, the students used the training they received to respond to the needs of peasants caught in the turmoil of the war. They helped rebuild bombed villages, teach children, set up medical stations, and organize agricultural cooperatives.

The workers' methods of reconciliation were often misunderstood in the atmosphere of fear and mistrust engendered by the war. They persistently refused to support either armed party

vn

and believed that both sides were but the reflection of one reality, and the true enemies were not people, but ideology, hatred, and ignorance. Their stance threatened those engaged in the conflict, and in the first years of the School, a series of attacks were carried out against the students. Several were kidnapped and murdered. As the war dragged on, even after the Paris Peace Accords were signed in 1973, it seemed at times impossible not to succumb to exhaustion and bitterness. Continuing to work in a spirit of love and understanding required great courage.

From exile in France, Thich Nhat Hanh wrote to Brother Quang to encourage the workers during this dark time. Thay Nhat Hanh ("Thay," the form of address for Vietnamese monks, means "teacher") wished to remind them of the essential discipline of following one's breath to nourish and maintain calm mindfulness, even in the midst of the most difficult circumstances. Because Brother Quang and the students were his colleagues and friends, the spirit of this long letter that became The Miracle of Mindfulness is personal and direct. When Thay speaks here of village paths, he speaks of paths he had actually walked with Brother Quang. When he mentions the bright eyes of a young child, he mentions the name of Brother Quang's own son.

I was living as an American volunteer with the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation in Paris when Thay was writing the letter. Thay headed the delegation, which served as an over

vm

seas liaison office for the peace and reconstruction efforts of the Vietnamese Buddhists, including the School of Youth for Social Service. I remember late evenings over tea, when Thay explained sections of the letter to delegation members and a few close friends. Quite naturally, we began to think of other people in other countries who might also benefit from the practices described in the book.

Thay had recently become acquainted with young Buddhists in Thailand who had been inspired by the witness of engaged Buddhism in Vietnam. They too wished to act in a spirit of awareness and reconciliation to help avert the armed conflict erupting in Thailand, and they wanted to know how to work without being overcome by anger and discouragement. Several of them spoke English, and we discussed translating Brother Quang's letter. The idea of a translation took on a special poignancy when the confiscation of Buddhist publishing houses in Vietnam made the project of printing the letter as a small book in Vietnam impossible.

I happily accepted the task of translating the book into English. For nearly three years, I had been living with the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation, where day and night I was immersed in the lyrical sound of the Vietnamese language. Thay had been my "formal" Vietnamese teacher; we had slowly read through some of his earlier books, sentence by sentence. I had thus acquired a rather unusual vocabulary of Vietnamese Buddhist terms. Thay, of course, had been teach

ing me far more than language during those three years. His presence was a constant gentle reminder to return to one's true self, to be awake by being mindful.

As I sat down to translate The Miracle of Mindfulness, I remembered the episodes during the past years that had nurtured my own practice of mindfulness. There was the time I was cooking furiously and could not find a spoon I'd set down amid a scattered pile of pans and ingredients. As I searched here and there, Thay entered the kitchen and smiled. He asked, "What is Mobi looking for?" Of course, I answered, "The spoon! I'm looking for a spoon!" Thay answered, again with a smile, "No, Mobi is looking for Mobi."

Thay suggested I do the translation slowly and steadily, in order to maintain mindfulness. I translated only two pages a day. In the evenings, Thay and I went over those pages, changing and correcting words and sentences. Other friends provided editorial assistance. It is difficult to describe the actual experience of translating his words, but my awareness of the feel of pen and paper, awareness of the position of my body and of my breath enabled me to see most clearly the mindfulness with which Thay had written each word. As I watched my breath, I could see Brother Quang and the workers of the School of Youth for Social Service. More than that, I began to see that the words held the same personal and lively directness for any reader because they had been

written in mindfulness and lovingly directed to real people. As I continued to translate, I could see an expanding communitythe School's workers, the young Thai Buddhists, and many other friends throughout the world.

When the translation was completed we typed it, and Thay printed a hundred copies on the tiny offset machine squeezed into the delegation's bathroom. Mindfully addressing each copy to friends in many countries was a happy task for delegation members.

Since then, like ripples in a pond, The Miracle of Mindfulness has traveled far. It has been translated into several other languages and has been printed or distributed on every continent in the world. One of the joys of being the translator has been to hear from many people who have discovered the book. I once met someone in a bookstore who knew a student who had taken a copy to friends in the Soviet Union. And recently, I met a young Iraqi student in danger of being deported to his homeland, where he faces death for his refusal to fight in a war he believes cruel and senseless; he and his mother have both read The Miracle of Mindfulness and are practicing awareness of the breath. I have learned, too, that proceeds from the Portuguese edition are being used to assist poor children in Brazil. Prisoners, refugees, health-care workers, educators, and artists are among those whose lives have been touched by this little book. I often think of The Miracle ofMind