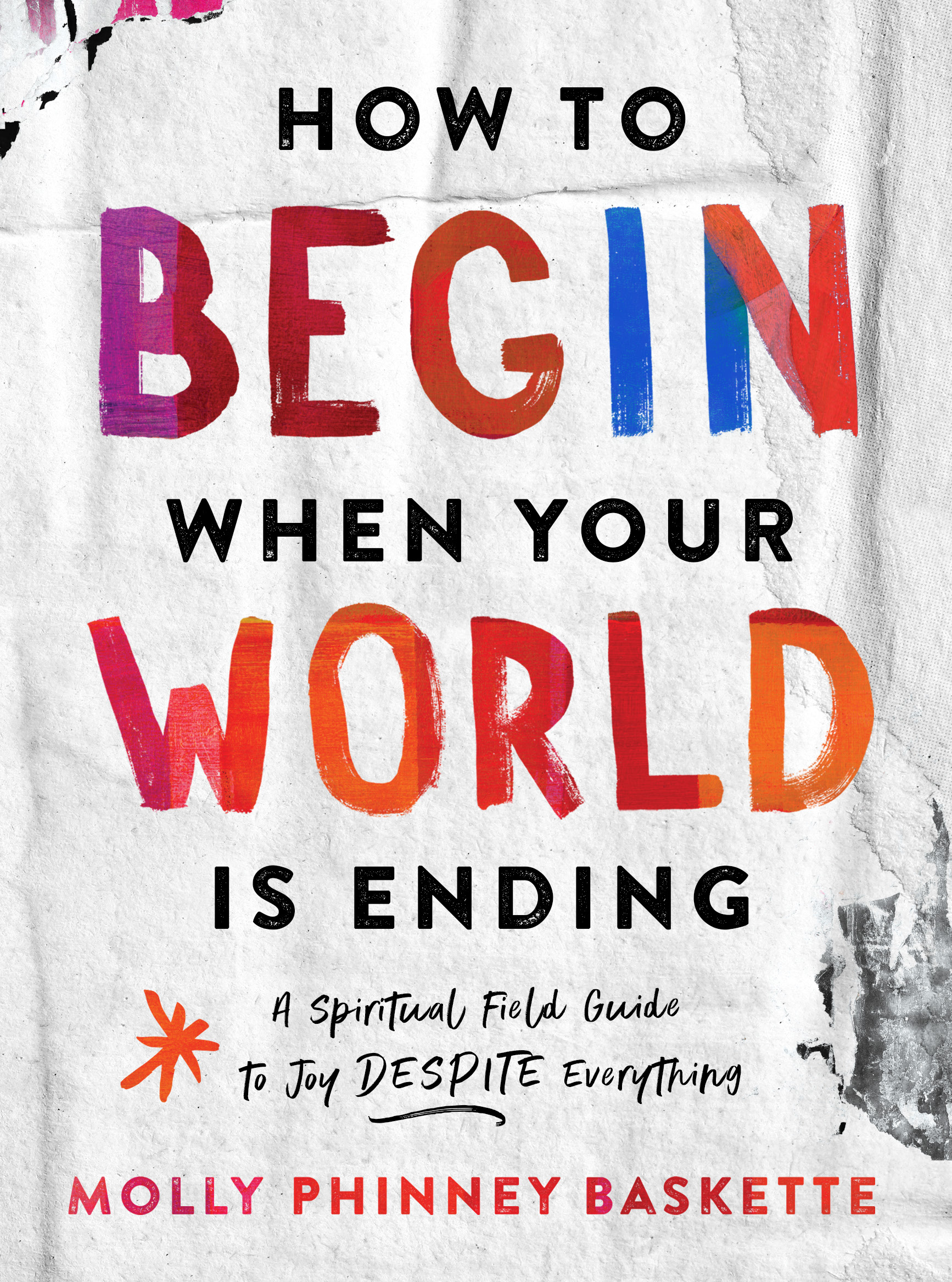

HOW TO BEGIN WHEN YOUR WORLD IS ENDING

Also by Molly Phinney Baskette

Remembering My Grandparent: A Kids Own Grief Workbook in the Christian Tradition (with Nechama Liss-Levinson)

Remembering My Pet: A Kids Own Spiritual Workbook for When a Pet Dies (with Nechama Liss-Levinson)

Real Good Church: How Our Church Came Back from the Dead and Yours Can, Too

Standing Naked Before God: The Art of Public Confession

Bless This Mess: A Modern Day Guide to Faith and Parenting in a Chaotic World (with Ellen ODonnell)

HOW TO BEGIN WHEN YOUR WORLD IS ENDING

A Spiritual Field Guide To Joy Despite Everything

Molly Phinney Baskette

Broadleaf Books

Minneapolis

HOW TO BEGIN WHEN YOUR WORLD IS ENDING

A Spiritual Field Guide to Joy Despite Everything

Copyright 2022 Molly Phinney Baskette. Printed by Broadleaf Books, an imprint of 1517 Media. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Email copyright@1517.media or write to Permissions, Broadleaf Books, PO Box 1209, Minneapolis, MN 55440-1209.

Cover design: Studio Gearbox

Print ISBN: 978-1-5064-8160-9

eBook ISBN: 978-1-5064-8161-6

This is a work of creative nonfiction. I have drawn material from my public blog, private journals, emails, and public testimonies by people in the churches I have served, as well as my own flawed and certainly subjective memory. Preachers, including me, often take poetic license for the sake of narrative flow. I also had new conversations with those whose stories I tellparishioners, friends and family membersincluding sending them early drafts and allowing them to correct the record, change identifying details, choose pseudonyms, or create composite characters with my assistance.

I tell everything that happened from my own perspective and tried not to make myself the hero of this story, but that wily old ego will creep in. I hope you will sense both the full humanity and the tenderness I hold for every person in this book, just as they are, and as they (and I, and you) are all still becoming. We all contain multitudes.

To all the people, in all of my churches and throughout my life, who have been God with skin on.

~

Jesus said, You ought always to pray and not to faint.

Do not pray for easy lives;

pray to be stronger people.

Do not pray for tasks equal to your powers,

but for power equal to your tasks.

Then the doing of your work will be no miracle

you will be the miracle.

Every day you will wonder at yourself and at the richness of life

which has come to you by the grace of God.

Julia Esquivel

CONTENTS

If you are unlucky, or that is to say, an ordinary human, you have emergencies. The thing you found in your teenagers room. The lump you found in the shower. The phone call that changes everything.

When I first heard the shocking news that I had a ball of cancer growing sneakily and silently inside of me, the first call I made was to my husband. By tacit agreement, Id been the unflappable one for the previous decade of our lives. But this time, he agreed to let me do most of the freaking out. It made that particular emergency a lot more bearable.

I first learned unflappability from a Robertson Davies novel, in which a village parson is called to the scene of a murder in the middle of the night. He doesnt race to the scene wild-haired with his PJs peeking out of his raincoat. He takes time to dress, wash, and compose himself before he gets there. He knows that whomever he meets at the other end will need his dignity, empathy, and strengtheven if he would have to fake it in the face of the calamitous.

When I became a pastor, I took this role to heart, which doesnt mean I always get it right. There was the time I raced to the ER to support a mom fleeing partner violence in the middle of the night. My car had gotten broken into earlier that day, and there was still broken glass everywhere. The exhausted mother and her two kids had to wait in the dismal, cold 1 a.m. hospital parking lot while I sweatily cleaned off the seat before driving them to a hotel for the night.

Then there was the time I cried my eyes out in public on the church lawn after a particularly fierce church fight, my heart broken at news earlier that week that my only brother had died by violence. Broken afresh by the pettiness and awfulness of anxious church people facing big decisions and putting me in their crosshairs, I wept.

There was the time I, a newly minted mother, brought my newborn to a restorative justice circle between a confirmed pedophile and the parents of the child he had sexually assaulted. I couldnt line up childcare, and I thought I could manage it the way Id handled so many other demanding, complex things in my life. (Whether it was the massive denial or just the cluelessness of being a new parent, I cant say.) My boy fussed, my boobs geysered ever-flowing streams, and I tried to low-key nurse with awkward beginning breastfeeding skills, holding back tears during one of the most devastating conversations Ive ever participated in.

These are exceptions (I think. I expect some notes from people in the know.) Mostly, over the years, Ive learned to pause when there are big feelings or big doings around me. I check in with God, who reminds me that whatever Im about to face is not quite the emergency I imagine. And I take my cues from there.

Thats what people in crisis need from God and Gods customer service reps: those of us offering first-line spiritual support. Someone recently devastated by the unimaginable looks into our face as they would look into a mirror. What they hope to see is that they will get through this.

And they will. We have, all of us, so far survived everything weve been through, to one degree or another. We know because we are still here. As for those who didnt survivethose who have died, by their own hand or anothers, by the villains of cancer or other catastrophesmy take is a question: do we really know they havent survived, too? (More on that later.)

When I began writing this book, I was sheltering in place along with forty million other Californians as well as people in every other state and around the world. We were hiding out not from a mass shooter, or an alien invasion, but from a microscopic virus similar in design to the common cold that we were told could kill up to 3 percent of the global population. Maybe this qualified as an emergency?

Eight weeks into the shelter order, the biggest problem in our house was that my husband was rationing toilet paper. I told him he could decide how many squares per week I could have when he grew a vagina. Meanwhile, India, a country with one billion people, went into lockdown with only four hours notice. Not enough time to purchase rice and beans, let alone toilet paper.

This pandemic changed all of our lives. It also ended many of our lives.

My biggest problem wasnt really the TP. Besides the expected anxieties about getting sick, my asthmatic children getting sick, or my elderly dad dying alone, I was sick at heart because I couldnt do my job the way I wanted to. Prudence and the internet dictated that, with my skill set, the most heroic thing I could do was stay home and binge-watch something called Tiger King .

I craved a larger purpose.

My arms ached from the hugs bottled up inside them. I wanted to get back to work helping people make meaning, if not sense, from the terrible things that happen to them, and I wanted to be able to do it in person, with a hand on their arm, and with a gaze directly into their eyes.

Next page