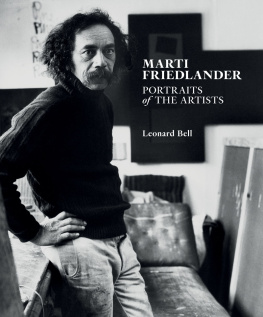

Self-Portrait

Marti Friedlander

with Hugo Manson

Contents

Dont be humble, youre not that great.

Golda Meir

1

Beginnings

At the orphanage, we were always told to begin our letters: I hope youre as well and happy as we are at present. But I was never that well and my sister Anne was never that happy. And we had nobody to write letters to anyway.

I was born Martha Gordon in Bethnal Green, London, on 19 February 1928. My parents were impoverished. They were refugees from the pogroms, living in the East End of London, which was the Jewish Quarter. Bethnal Green was Jewish, then; now its Bangladeshi. Thats how it should be. I love the hopefulness of migration, of people trying to better themselves, wanting a better education for their families and children, then moving onwards.

My parents had come, as far as I know, from Kiev in Russia. I know very little about them. The reason I know very little is that my sister and I were placed in an orphanage, the Ben Jonson Home in Mile End, run by the London County Council, when I was three and she was almost five. It was an awful place. It was a practice there to use the ruler every day on every child just to tell them that they should not misbehave. That is my earliest memory. I remember other things from the Mile End home: I remember sitting at a table at breakfast time with the chairs still up on the table, being forced to eat a meal that I hadnt been able to digest the night before. I was a very sick child, but they obviously hadnt picked that up and they were forcing me to eat the food. But I try not to hold on to too many of those sorts of memories because you have to move on.

When I was five, by some miracle, my sister Anne and I were taken from the Mile End home and put in the Jewish orphanage in Norwood, the Norwood Orphan Aid Asylum. It saved my life. I would love to know how we got there, or even how they knew there were two Jewish children in the Mile End home Ive never been able to find out. But we were rescued from the Mile End home and it saved my life.

It wasnt until Shirley Horrocks took me back to meet the Norwood after-care committee in 2004, when she was making a documentary about me (Marti: The Passionate Eye), that I learned there was some mystery about my father which nobody seemed to want to share. You wonder. With my mother, I do know things. My parents must have suffered terribly, particularly in losing their two daughters that was the fate of so many Jewish people. But I dont want to talk about them further, because I value them too much. I want anything I say about them to be a validation rather than anything else.

....................

Growing up in the Jewish orphanage was one of the best things that ever happened to me. I was born with a deformed duodenum so that I couldnt digest solid food. As a small child I was in tremendous pain and fainted all the time. The feeling of fainting was the most awful. At the age of eleven I was three feet in height and weighed three stone. I couldnt even hold a netball. But the Jewish orphanage gave me access to the best medical care available. There was a Jewish hospital in London staffed by Jewish surgeons and doctors, many of them at the height of their profession. My first operation there made it possible for me to eat.

My sister Anne is only fifteen months older than I am, but we have totally different feelings about the orphanage. I think thats the way it is all through life. Youre born with a character and youre born with a personality and nothing changes that. Its just the way that you perceive and react to life.

Anne likes to go back into the past, but I dont. Im not ready (even though Im doing it now, and I ask myself, how have I been persuaded?). I always say to Anne that Im still living very much in the present. But she reminds me that at the age of six, sitting on a bed in the dormitory and I do remember it very clearly she asked me what Id like to do when I was older, and I said I want to travel the world. It seemed unbearable to me, to think that there was a whole world out there and I might never see it. Anne says, even now, that she thinks it unbelievable I should have expressed such urgency. But it wasnt unbelievable. I think that when you are ill as a child you have a kind of urgency about life that other children just dont have.

Photographer unknown, Martha and Anne Gordon, late 1940s

Anne always hated being in the orph an age. She says that she would have preferred to have been brought up in a family. I felt differently; the orphanage was where I was, and I received a great deal of affection there. But we probably wouldnt have survived if we hadnt had each other we had an especially close relationship, and we tended to have our most intense friendships with each other. Anne felt a responsibility to be a mother to me, to protect me, but I was too fiercely independent to be mothered. She says I was always the leader. I was terribly tiny but it was true. If there was anything that needed to be dealt with I would always go straight up to the headmistress and say, this needs to be resolved. It may be, also, that my receiving so much attention was difficult for a sister, but she says no, it was never difficult for her. She was a sportswoman, and she wrote poems that were reproduced in our magazine I thought they were fantastic. She still writes, mainly screenplays these days. And we are still very close, but now we live far apart.

We were lucky, in a way: not knowing much about our background, we could fantasise about our antecedents, and we did. I cant say that its a good thing to grow up in an orphanage. But sometimes, when people say with pity, Oh, you grew up in an orphanage, I look at them and say, But you grew up in a nuclear family, there must have been incredible tension. And of course they often admit that it wasnt always so wonderful after all.

Love is the most energising thing. Even in the orphanage I was fortunate to receive a great deal, which gave me the ability to recover. Its what you wish for every child. A lot of the children in the orphanage probably didnt feel that they had so much love; some were traumatised. Many of them had a parent still living, who came to visit once a month on visitors day. Anne and I never had visitors. There was no one to visit us. But children just dont give up. We would stand there by the gate, thinking that we might have visitors this is becoming painful for me to remember. The other children would be given parcels of kosher food, wonderful delicacies. But they were always generous and would share it with others.

The orphanage taught a very strong ethical code. I can remember picking up a farthing in the street and handing it to the headmistress. We were given a halfpenny every week for spending money, so an extra farthing in those days was like a fortune, but I would never have thought of keeping it. It was just part of the ethos of the teaching there.

I loved school. I was desperate to learn. In my early years in the orphanage, aside from Anne it was the teachers who had a strong effect on me. One in particular thought I was very bright I had written something clever and he gave me a penny as a reward. I was so flattered. I wanted all my life to meet him again because I felt he had had such an influence on me. Years afterwards, I saw this teacher in a Jewish vegetarian restaurant in Hampstead; he would have been in his eighties then. I went up to him, expecting that he would remember me. Of course he hadnt a clue who I was. I thought I would have been unforgettable. Another salutary lesson in life.