ADVANCE PRAISE FOR

Liberal and Illiberal Arts

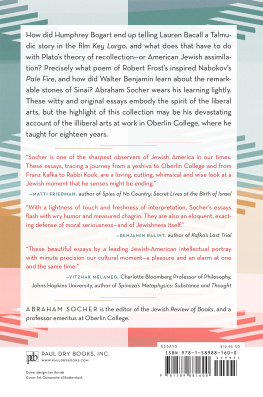

With a wicked wit and expansive erudition, Abraham Sochers collected essayswritten, as he says, while playing hooky from academic researchadd up to much more than the half-dozen scholarly books that he might have written on the job. Whether pondering the meaning of death in the Kaddish, dissecting a series of ugly incidents at Oberlin College, or riffing on American popular culture, Socher offers succinct and bracing wisdom for our contentious times. Taken together, Liberal and Illiberal Arts establishes Socher as a master of the art of the essay. David Biale, Emanuel Ringelblum Distinguished Professor of Jewish History, University of California, Davis, and author of Gershom Scholem: Master of the Kabbalah

Liberal and Illiberal Arts is at once both dazzling and engaging. David Ellenson, Chancellor Emeritus of Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, and author of Jewish Meaning in a World of Choice

In an era where our intellectual life is muddy with ideology, our religious life muddy with politics, our political life muddy with moral posturing, and our morality muddy with self-righteousness, Socher performs an enormous public service and clears away the mud. In this moving collection, he offers us what we direly need: clarity. Dara Horn, author of People Love Dead Jews

What has Los Angeles to do with Jerusalem? More than you might think, Abraham Socher shows in these wonderfully learned and inviting essays. Here Bogart and Maimonides, baseballs steroids scandal and a raucous party at a 19th-century yeshiva, Nabokovs Pale Fire and the Kaddish prayer, all mingle happily, brought together by Sochers love of intellectual exploration. Plenty of books have been written in defense of the idea of the liberal arts, but this one is a living example of their power to charm and enlighten. Adam Kirsch, author of The Blessing and the Curse: The Jewish People and Their Books in the Twentieth Century

Abraham Socher is that rare writer who combines a light touch with vast learning and deep insight. On matters as ostensibly diverse as classical Jewish thought, the history of baseball, the relationship of philosophy to religion, and the groupthink currently undermining colleges and universities, he has valuable things to say and says them in a delightful style, leavened by subtle wit. Jon D. Levenson, Albert A. List Professor of Jewish Studies, Harvard Divinity School, and author of The Love of God: Divine Gift, Human Gratitude, and Mutual Faithfulness in Judaism

With his insatiable curiosity, eye for the killer detail, and frame of reference wide as the diaspora, Abraham Socher is an essayist for the ages. These gems remind us what the rabbis meant by learn: to inquire as deeply of texts as one does of life, death, and love. Esther Schor, Leonard L. Milberg 53 Professor of American Jewish Studies, Princeton University, and author of Bridge of Words: Esperanto and the Dream of a Universal Language

Socher has an enviable command of Jewish texts, ancient, modern, esoteric, and popular. But hes not just a scholar. Hes a magician. In these lovely, lucid essays, Socher turns his considerable erudition into deceptively plain prose. Encountering cant and contradiction, he politely slices them asunder. We who care about Jewish ideas and letters are lucky to have a Socher to keep them honest and intelligible. Judith Shulevitz, author of The Sabbath World

Few master the complexities of contemporary culture as deftly as Abraham Socher, whose breadth of knowledge never fails to astonish. To all that he touches, he brings an uncommon blend of erudition, wit, and moral engagement. Steven J. Zipperstein, Daniel E. Koshland Professor in Jewish Culture and History, Stanford University, and author of Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History

First Paul Dry Books edition, 2022

Paul Dry Books, Inc.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

www.pauldrybooks.com

Copyright 2022 Abraham Socher

All rights reserved

ISBN-13: 978-1-58988-160-0

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021952879

For Shoshana

Contents

A LITTLE OVER twenty years ago, I interviewed to be an assistant professor of Jewish history at a big state university, which Ill call the U of A. After giving a job talk about the quirky philosopher-heretic Solomon Maimon, in which I tried to impress a skeptical just-the-facts-maam historian with my command of the demography of eighteenth-century East European Jewry, I was taken to meet an associate dean (big building, small office, blue blazer).

The dean, who was a scientist of some kind, asked me if I enjoyed teaching. I leapt into an enthusiastic, largely sincere bit about the first-year humanities courses I was teaching as a post-doc at Stanford that year. Two or three sentences in, the dean waved me off. Oh, I dont care, he said, its just something Im required by the state legislature to ask you. Were an R-1 university. Youll live and die here based on your research: for tenure, youll need several articles in peer-reviewed journals in your subfieldyou guys do have those, dont you?a book with an excellent university press and maybe another one on the way, or at least an active research agenda.

Although Id never before heard the term R-1 university (perhaps because the schools I had attended thought that they were tiers unto themselves), I knew the rest. Still, the bluff, bureaucratic good humor with which this dean of arts and sciences dismissed the importance of how I would teach shortly before offering me a job as a teacher was startling. Also, Id never quite thought of what I actually didbrowsing in the library stacks, making fortuitous connections, thinking hard about a literary passage or philosophical argumentas research, exactly. Sitting in the deans office with my careerist academic game face on, I suddenly realized that he didnt really care what research in the history of Jewish philosophy, or the philosophy of Jewish history, or whatever it was that I did, amounted to. All that mattered was that there was a way to quantify it and a tenure line in his budget. (The fact that this line was probably funded by a donor less concerned about Jewish history than about the Jewish future of U of A undergraduates was something to which neither the dean nor I gave a second thought.)

In the end, I took a position at Oberlin College instead. They had more or less the same tenure requirements, but, to their credit, the Oberlin faculty and dean made it clear to me that I would also have to become an excellent teacher. More importantly, the studentsbright, curious, questingmade it even clearer that they would make me ashamed of myself if I didnt. They were, many of them anyway, interested in knowledge for its own sake, though they also were encouraged to think that it would end up coinciding with personal, political, and perhaps even spiritual virtue. Indeed, that dubious equation was literally Oberlins selling point (Think one person can save the world? So do we, read the admissions tagline).

Next page