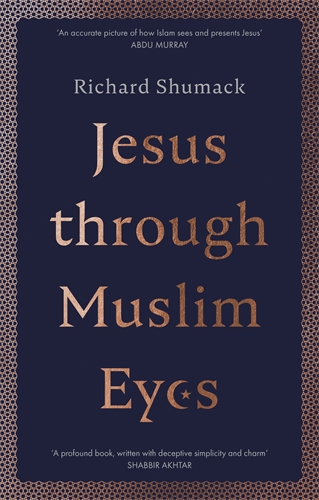

Dr Richard Shumack lives in Sydney, Australia. He is a philosopher of religion specializing in Muslim and Christian belief. He is the Director of the Arthur Jeffery Centre for the Study of Islam at Melbourne School of Theology, the Academic Director of the RZIM Understanding and Answering Islam program, and a research fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity (CPX), Sydney, Australia. Richard has published many articles in the Australian media.

I strongly recommend Jesus through Muslim Eyes : if you care about Muslim-Christian relations, this book is significant.

Dr Muhammad Kamal , Asia Institute, University of Melbourne

This is a profound book, written with deceptive simplicity and charm, like your previous book on Christianitys encounter with Islam. Its conclusions are fair-minded, provocative and devastating for any who think simplistically about the Jesus Christ of Christian faith and the Isa ibn Maryam of the Quran.

Dr Shabbir Akhtar , Faculty of Theology, University of Oxford

In this excellent book, Richard Shumack strikes the perfect balance between academic rigour and accessibility. Its discussion of the Islamic Jesus is lucid, and its application to the needs of Christian readers is highly relevant.

Professor Peter Riddell , Professorial Research Associate, SOAS University of London

Richard Shumacks familiarity with Islam gives him the ability to present a true picture of the religion in a way that is not unfair or uncharitable. Rather, he describes for us an accurate picture of how Islam sees and presents Jesus and compares that picture with the Jesus of history. Shumack has a knack for raising interesting questions and thoughtful arguments while expressing them in easy to understand ways. In Jesus Through Muslim Eyes he does just that.

Abdu Murray , author of Saving Truth: Finding Meaning and Clarity in a Post-Truth World

This is an honest and scholarly analysis of the Muslim Jesus, the Christian Jesus, and the diverging paths Muslims and Christians chose to follow. It brings profound new insights into the historical, philosophical and textual discussions about Jesus. It is an excellent contribution to both contemporary Christian-Muslim dialogue and the historical Jesus.

Anwar Mehammed , head of Islamic Studies at the Ethiopian Theological College, Addis Ababa

First published in Great Britain in 2020

Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge

36 Causton Street

London SW1P 4ST

www.spck.org.uk

Copyright Richard Shumack 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

SPCK does not necessarily endorse the individual views contained in its publications.

Scripture quotations are from the ESV Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version), copyright 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Quran version: Translation of the Meaning of the Quran , Saheeh International Translation, Abdulqasim Publishing House: Riyadh, 1997.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780281081936

eBook ISBN 9780281081943

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by The Book Guild Ltd, Leicester

First printed in Great Britain by Ashford Colour Press

eBook by The Book Guild Ltd, Leicester

Special thanks to my new friend and editor Tony Collins (at SPCK) for believing in the project, and to my old friend and colleague Natasha Moore (at CPX) for continuing to teach me how to write properly. Without either of you this book would not have come to be.

Contents

A quick word about terms

Choosing words can be tricky in religious discussions. The same word can mean different things in different religions or be used variously within a religion. When the religions involved depend upon scriptures written in a number of ancient languages there is the added problem of translation. Despite these complexities, I have chosen in this non-scholarly book to, wherever possible, use the simplest English word available.

So, for example, in Islam the divine creator of the universe is called by the Arabic term Allah. In Christianity and Judaism this creators proper name is the Hebrew term Yahweh. In English, the generic term for this creator is God. Outside of direct quotes, then, I will simply speak of God. Similarly, I will speak of the English Jesus and not the Muslim Isa .

One choice Ive made is important to note. The word gospel is both central to this discussion and used in various subtle ways in Christianity and Islam. I have adopted the following convention:

Gospel the four biblical (canonical) biographies of Jesus.

gospel any non-biblical biography of Jesus.

injeel the biography of Jesus described by the Quran.

message of Jesus the content of the gospel (lit. good news).

Prologue: Meeting Jesus

Like many Australians of my generation, I first met the Christian Jesus as a little kid. He was the Jesus of church Sunday School and primary school Scripture classes. For me he was, mostly, the Jesus of Christmas nativity scenes and the Easter Bunny. In my imagination, his (Australianized) life began in a sheep trough in a bush shed, skipped across a few un-confronting and fun miracles like walking on water and landed at his resurrection because, you know, Easter Eggs! I remember hearing very little talk about things like him being a holy, divine Lord or him dying horribly on a cross. Instead, for me, his soundtrack was Carols by Candlelight. There, the Jesus of Silent Night was meek and mild. Whether through my disinterest, or the well-meaning design of my teachers, the biblical records of Jesus had been censored to create a G-rated Jesus. If I had any interest in this Jesus at all, it was well gone by the time I became a teenager. Football, music, mucking about in the bush, and, of course, girls all appeared vastly more attractive and so there were far more important people to hang around with than him.

It was much later, at university, that I came to say that I had properly met the Christian Jesus. There, through reading the Bible on its own terms, I was confronted with the Jesus of the Gospels in all his rich complexity. In this grown-up encounter (and much to my surprise) I discovered a Jesus whose supernatural origins carried profound worldview implications, whose miraculous acts were soaked in hitherto unrecognized layers of religious meaning, and whose extraordinary earthly end forced me to face the mysteries of my mortality. For me, at that crucial formative time of life, this Jesus offered me the best explanation of both the universe and my place in it. Perhaps more importantly, he also seemed to empower me to be a better person. The spiritual icing on the cake was that my philosophical and moral awakening was accompanied by a range of supernatural experiences including a miraculous healing that seemed to confirm that Jesus, was indeed, who he claimed to be: the resurrected, divine, Lord of my life. Obviously, this encounter forced me to abandon my earlier notions of Jesus. The Christmas and Easter Jesus of my childhood was revealed as a superficial, childish myth. The biblical Jesus who replaced him was compelling, so I followed.